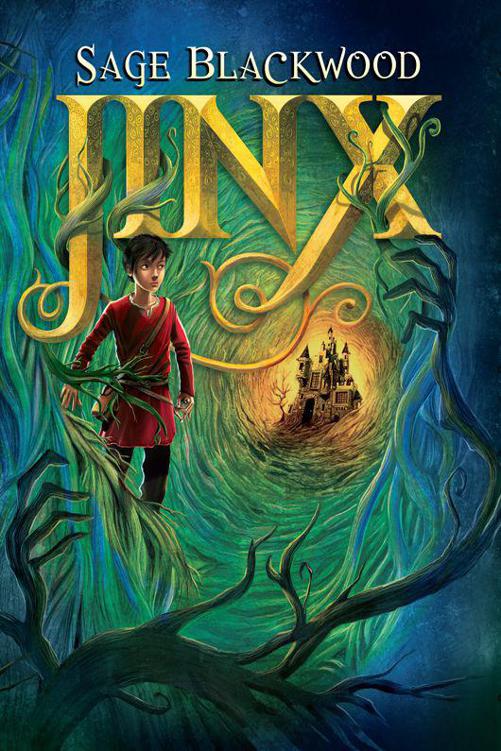

Jinx

Authors: Sage Blackwood

Dedication

Dedication

To Jennifer Schwabach

because it’s her kind of story

8. The Spell with

Something Wrong about It

Jinx

I

n the Urwald you grow up fast or not at all. By the time Jinx was six he had learned to live quietly and carefully, squeezed into the spaces left by other people, even though the hut he lived in with his stepparents actually belonged to him. He had inherited it after his father died of werewolves and his mother was carried off by elves.

But then a spark from a passing firebird ignited the hut, and within a few minutes it had gone. The people in the clearing built another to replace it, and this new hut was not his. His stepparents, Bergthold and Cottawilda, felt this keenly. Besides, the harvest had been bad that autumn, and the winter would be a hungry one.

This was the sort of situation that made people in the clearing cast a calculating eye upon their surplus children.

And Jinx was definitely surplus, especially since Bergthold and Cottawilda had a new baby girl of their own. He worked as hard as he could to make up for the crime of existing, and he tried not to eat too much. He only took a single bite of his toad porridge every night before offering the rest to the baby. Nevertheless, his stepparents agreed between them that Jinx was too much trouble and expense to raise.

So late one autumn afternoon Bergthold told Jinx to put on his coat, and together they left the clearing where they lived and plunged into the Urwald. They followed the path where it twisted between great trees as big around as cottages. Then Bergthold stepped off the path.

Jinx stopped.

“What are you waiting for?” Bergthold roared. “Come on!”

“‘N-never stray from the path,’” said Jinx. This was a rule every child in the Urwald was taught as soon as it could walk.

“We’re straying from it now!” Bergthold grabbed Jinx by the front of his coat, cuffed both his ears, and hauled him from the path.

Jinx struggled in his stepfather’s grip. Leaving the path was

wrong

. The path and the clearings of the Urwald belonged, just barely, to people. Everything else belonged to the trees. Anyone who ventured off the path was doomed.

Bergthold hit Jinx again, gave him a hard shove, and marched him into the forest.

Jinx walked, his ears burning. He made his way through the deep twilight of the Urwald, and every now and then Bergthold gave him a little shove to the left or the right around a great glowering tree, and Jinx thought that Bergthold was making sure that Jinx wouldn’t be able to find the path again.

“Stop here!”

Jinx stopped instantly, not wanting to get hit again. He wondered if Bergthold was going to kill him.

“Sit down, and stay right here, and don’t move until nightfall, or you’ll wish you had never been born.”

Jinx already wished he had never been born. But he sat down in the moss, where his stepfather pointed. He could feel the Urwald’s disapproval seeping up through the ground.

“Good. And good-bye.” Bergthold turned to go. Then he stopped, looking around him. He started off in one direction, then stopped, came back, and started off in another direction. Then he came back again.

He gave Jinx a rather furtive look. “Do you, er, happen to remember which way we came?”

“No,” said Jinx.

“Ah,” said Bergthold. He nodded, as though he was just thinking about things.

He’s lost, Jinx thought. We’re both lost.

“I think I know which way the path is, though,” Jinx hazarded.

“Ah! Well, don’t just sit there like a lump on the ground—lead on, boy!”

Jinx scrambled to his feet and started walking. He really had no idea where the path was. But at least moving, with Bergthold behind him, felt safer than sitting still, alone, under the Urwald’s menacing shadows. And probably being watched by hungry creatures in the trees.

Rounding a great gnarled knot of a tree trunk, Jinx ran smack into a creature and yelped.

“Calm down, boy, I won’t eat you,” said the creature.

Since this was by no means a given in the Urwald, Jinx did calm down. The creature was a man, tall and thin, with twisty hair, yellow eyes, and a pointed beard. He was dressed in a long purple robe. His feet were bare and knotty, and he carried a basket—he had been harvesting mistletoe.

Jinx had never met a wizard. He had always heard they had long white beards, not short pointy brown ones. But magic poured off the man, ripples of magic as strong as the pulses of life that seeped from the trees all around them.

“Just walking in the woods with my boy, sir,” said Jinx’s stepfather, too hastily and without any greeting at all.

You didn’t tell people your business in the Urwald, and the wizard’s nose twitched at the bad smell of the lie. “Pretty late for straying off the path,” he said.

“Gotta teach the boy to find his way in the woods.”

The wizard’s nose twitched more. You didn’t learn to find your way in these woods—you stayed out of them. “Some people abandon their children in the woods,” said the wizard. “If they find it too much trouble to feed them.”

“Not their own children!” said Bergthold. “Stepchildren, maybe, now I’ve heard of that.”

The wizard looked at Bergthold through a dark cloud of disapproval. “If you marry the mother, you accept the children.”

“I

didn’t

marry the mother,” said Bergthold, aggrieved. “She died years ago. I married the woman who was married to the man who had married the mother. The boy’s got a curse on him—everyone who takes him dies.”

“Actually, that seems like a fairly normal death rate for the Urwald.” The wizard looked at Jinx so hard that Jinx wanted to hide. “I happen to have need of a boy. I’ll take him.”

“Buy him, you mean,” said Bergthold.

“Curse and all?”

“He’s worth more with the curse!”

“Everyone who takes him dies?”

“You could probably use that,” said Bergthold. “You know, against your enemies.”

The wizard sighed. “Very well. I will pay one silver penny.”

“A silver penny? A measly silver penny for a boy like this?” Bergthold drew himself up. “A boy with a valuable curse? You insult me, sir!”

A dangerous glitter flickered across the wizard’s face, and Jinx shot his stepfather a nervous glance. Bergthold was frightened and angry, as he usually was, but the fear was ripply with greed.

“A silver penny is a lot for a boy with a curse on him,” said the wizard.

Somewhere behind them there was a crunching sound, as of a fallen stick breaking under a very large foot. Jinx peered anxiously into the terrifying gloom. His stepfather was too wrought up to notice.

“A boy like this is worth three silver pennies at least!” said Bergthold.

This was rather a surprise to Jinx, who was regularly told by both Bergthold and Cottawilda that he wasn’t worth a rotten cabbage leaf.

“He’s a hard worker, too! Especially if you beat him,” said Bergthold. “And you hardly have to feed him at all.”

“Well, I can see you haven’t been,” said the wizard. “One penny’s my final offer.”

There were more crunching sounds, sticks snapping, and the hollow scrabble of clawed feet on the forest earth. Jinx looked this way and that but couldn’t see anything moving. He looked back at the two men and wished he could trust either one of them.

“Two silver pennies then,” said Bergthold.

“One silver penny,” said the wizard, sounding suddenly indifferent to the whole thing. “You had best take it quickly.”

“Never!”

“Come here, boy,” the wizard commanded.

Several things happened at once. Jinx took a nervous step toward the wizard. From the forest behind him, heavy, ragged breathing joined the sound of clawed feet, and Jinx was overwhelmed by a smell like rotting meat. Jinx whirled around and saw trolls—they must be trolls, they were so big and tusky—crashing through the trees, bearing down on him and his stepfather. The wizard reached out and grabbed Jinx. A pale green cloud of calm surrounded the wizard all through what happened next, and it was because Jinx could see this cloud that he stood perfectly still, even though his legs wanted to run.

With a roar of triumph one of the trolls seized Bergthold around the waist and hoisted him to his shoulder. The other trolls howled with glee and danced about. A troll’s claw swung right past Jinx’s nose—he felt the breeze and smelled the rancid breath. Bergthold screamed and reached his arms toward Jinx, beseeching. Jinx shrank back against the wizard. The wizard didn’t move. Jinx expected to feel the trolls’ claws grabbing him at any second.

But the trolls didn’t seem to see Jinx.

The party of trolls thumped out of the clearing. Jinx had a last sight of his stepfather, head bumping down against a troll’s back, screaming and red faced—Bergthold’s hat fell off and rolled away. Jinx broke away from the wizard and ran to pick it up.