Japan's Comfort Women (32 page)

Read Japan's Comfort Women Online

Authors: Yuki Tanaka

Tags: #Social Science, #Ethnic Studies, #General

The facilities included:30

Ginza & Marunouchi area

•

Cabaret:

1

Oasis of Ginza with 400 dancers

2

Senbiki-ya with 150 dancers

3

K

d

ichiro with 20 dancers 4

Ryokuryoku-kan with 50 dancers

5

Ginza Palace [number of dancers unknown ]

•

Beer hall: T

d

h

d

beer hall

144

Japanese comfort women for the Allied forces

•

Dance hall: It

d

-ya with 300 dancers •

Bar: Bordeaux

•

Billiard parlour: Nish

d

-kan •

Restaurant (for officers): K

d

gy

d

Club

Shinagawa area

•

Cabaret: Paramount with 350 dancers

Shibaura area

•

Cabaret and comfort station: T

d

k

d

-en with 30 dancers & 10 comfort women

MukDjima area

•

Banquet house (for high-ranking officers): The

i

kura Villa

Itabashi area

•

Comfort station: Narimasu comfort station with 50 comfort women

Akabane area

•

Cabaret: Koz

d

-kaku with 100 dancers

Koishikawa area

•

Cabaret: Hakusan cabaret [number of dancers unknown]

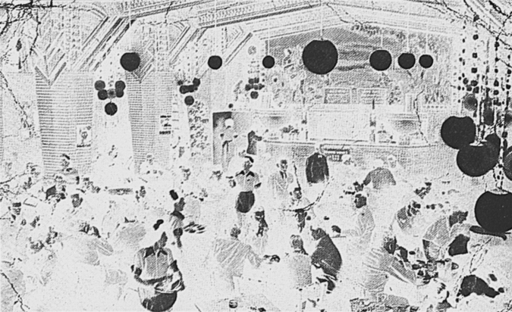

Plate 6.3

T

d

h

d

Beer Hall in Ginza was a popular attraction for the Allied servicemen.

During the Korean War this place was also frequented by US and Australian soldiers on Rest and Recreation leave.

Source

: Australian War Memorial, transparency number 044191

Japanese comfort women for the Allied forces

145

Keihin area

•

Comfort stations:

1

Komachien with 40 comfort women

2

Miharashi with 44 comfort women

3

Yanagi with 29 comfort women

4

Hamakawa with 54 comfort women

5

Gok

e

rin with 45 comfort women & 6 dancers 6

Otome with 22 comfort women

7

Rakuraku-en with 20 comfort women

[in addition, three sub-contracted comfort stations – Matsuasa, Sawadaya and Fukury

d

]

Santama area

•

Comfort stations:

1

Ch

d

fuen with 54 comfort women 2

Fussa with 57 comfort women

•

Cabaret and comfort stations:

1

New Castle with 100 comfort women & 150 dancers 2

Rakuraku House with 65 comfort women & 25 dancers 3

Tachikawa Paradise with 14 comfort women & 50 dancers 4

Komachi with 10 comfort women & 10 dancers

Sangenjaya area

•

Officers’ club: Comfort station exclusively for officers (comfort women were sent from other comfort stations as required)

Ichikawa city (Chiba prefecture)

•

Cabaret for officers : Dream Land

Atami (Shizuoka prefecture)

•

Hotel: Tamanoi Bekkan

•

Hotel & cabaret: Fujiya Hotel

•

Cabaret & dance hall:

i

yu Given the severe economic depression, it was not difficult for the RAA, which was set up with an extraordinarily large sum of capital, to purchase suitable properties and convert them for use as comfort stations, cabarets, dance halls and the like.

Various types of properties were available cheaply immediately after the war. The RAA’s initial difficulty was to secure enough comfort women. Many parts of Tokyo had been burnt out in US napalm attacks, including those in red-light districts.

Moreover, the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Headquarters had issued an order in March 1944 for all brothels, bars, geisha houses, and high-class restaurants to stop business. By mid-1944 most sex workers in Tokyo had left. Thus, the RAA had to use labor brokers to recruit former prostitutes from Tokyo’s neighboring prefectures and encourage them to work as comfort women for the occupation troops.31

146

Japanese comfort women for the Allied forces

At the same time the RAA tried to recruit women through newspaper advertisements. For example, both

Yomiuri HDchi

and

Mainichi Shimbun

carried the following advertisement on September 3 and September 5.32

Urgent Notice

Special female workers wanted

Free meals & accommodation, high salary, advance payment also available Travel expenses paid for applicants from countryside Tokyo, Ky

d

bashi, Ginza 7-1

The Special Comfort Facilities Association

Phone: Ginza 919-2282

The RAA could provide free meals to its employees with food supplied by the Metropolitan Government Office as arranged by the police authorities.33 This supply had probably been built up on rationing control during the war.

The RAA put up a large recruitment poster in front of its office in Ginza, which said:

Announcement to New Japanese Women! We require the utmost cooperation of new Japanese women who participate in a great project to comfort the occupation forces, which is part of the national emergency establishment of the postwar management. Female workers, between 18 and 25 years old, are wanted. Accommodation, clothes and meals, all free.34

Although these advertisements avoided the words “comfort women,” most people who read them would have been clear about what sort of work was being advertised. It is said that many “taxi dancers” were recruited through newspaper advertisements. As the condition of “free meals and free accommodation” was extremely attractive, the jobs enticed not only previous entertainers but young women who had become war orphans and young widows who had lost their husbands in the war. They were attracted to work as a “dancer.” However, as time passed, the boundary between “dancers” and “comfort women” became blurred; many “dancers” were gradually dragged into the prostitution business as well.35

It is not surprising that this kind of blatant advertising upset some nationalists.

For example, one day, a surviving former

Kamikaze

pilot stormed into the RAA office in Ginza, holding a drawn sword, and shouted: “I am going to kill the traitors to the nation!” The workers in the office somehow managed to calm him down by saying that they were doing the work purely out of patriotism, to protect the majority of Japanese women, and that really they deeply resented the Americans.36

On August 29 a group calling itself the National Salvation Party put up leaflets at various places in Shinbashi railway station near Ginza, which said: Notice to the Women of the Japanese Imperial Nation!

The women of our imperial nation must not have intercourse with the

Japanese comfort women for the Allied forces

147

black race. Those who violate this order deserve the death sentence.

Therefore make absolutely sure to keep the purity of the Yamato race!37

It is interesting to note that this propaganda identified only the black race as the foreign group that would contaminate “the purity of the Japanese blood,” not white men – perhaps a reflection of popular Japanese feelings of inferiority towards Caucasians.

Despite having given the RAA initial verbal permission for “open recruitment,”

two months later the police issued an instruction warning the RAA and its labor brokers not to “unfairly recruit women by using exaggerated or false expressions or by suppressing the names of employers.”38 The existence of this police document strongly suggests that many of those employed by the RAA had been deceived or trapped into the prostitution.

According to the memoirs of Kaburagi Seiichi, who was a public relations officer for the RAA, it was Komachien (which loosely translates as “The Babe Garden”) in the

i

mori district of the Keihin area which was first opened as a comfort station. It opened on the morning of August 28, the day that the RAA’s inauguration ceremony was conducted in front of the Royal Palace.39 This was also the day that 46 planes of the advance party arrived at Atsugi airbase on the outskirts of Tokyo. Indeed, some GIs from this advance party visited Komachien that very evening.40 It is probable they found the comfort station on the way from Atsugi to Kanagawa prefecture, where they had to inspect the port facilities of Yokosuka in preparation for the landing of US marines a few days later. The selection of the site – on the highway linking Tokyo, Yokohama and Yokosuka – was a deft business decision by the RAA.

By the time the occupying forces landed, the RAA had managed to set up only Komachien. As a result this comfort station was flooded with GIs from as early as August 30. There were only 38 comfort women in the station. Given the demand, they hardly had time to rest or have a meal. Shortly thereafter, the RAA recruited new women, managing to increase the number of comfort women at the station to 100. Even then, it is said that the minimum number of clients that each comfort women had to serve each day was 15. One woman was said to have served 60 GIs a day.41

GIs paid their money at the front desk and received a ticket and a condom.

They gave the ticket to the comfort women who served them.42 This procedure replicated that used at the Japanese military comfort stations during the war.

The physical hardship that these Japanese comfort women faced was strikingly similar to that endured by Asian comfort women during the war. The only difference was that these Japanese comfort women were paid properly, in most cases, whereas the former had received hardly any payment. The tariff was 100

yen for a so-called “short service.” The women collected the tickets that GIs handed to them and then, on the following morning, took the tickets to the accounting office of the comfort station. Each comfort woman received half of the tariff – 50 yen – for each ticket. The other half went into the RAA’s coffers.

The RAA provided the women with the necessary clothes and toiletries, and 148

Japanese comfort women for the Allied forces

with free meals.43 This arrangement was considerably better than that experienced by prostitutes, not to mention comfort women, before and during the war.

Under the old regulations, the employing brothel owner took 75 percent of the tariff, the prostitute having to use her 25 percent to cover the costs of clothes, cosmetics and meals, which were deducted.44 It was conceivable that, given the general economic situation at the time, many newly recruited comfort women borrowed money in the form of advanced payment.

In order to meet the heavy demand, the RAA purchased several large Japanese restaurants in the district and converted them to comfort stations over the following two months or so. At the same time the RAA quickly expanded its business operations, eventually owning and operating “entertainment facilities”

in Atami and all over the metropolitan area.

Another area where the RAA concentrated the establishment of its comfort stations, on the advice of the metropolitan police authorities, was in the Santama area, particularly Tachikawa and Ch

d

fu districts. To accommodate the US

occupation forces who advanced to Tachikawa airbase after September 3, a comfort station called Fussa was opened there on September 5. This station was set up in the building used as a dormitory for the riggers at the Tachikawa Imperial Army airbase. Within a short time comfort stations were opened one after another in this district.45 According to Mark Gayn, correspondent for the

Chicago Sun

, who was sent to Japan to report on the occupation, the RAA brought a truck full of comfort women to the unit stationed near Ch

d

fu, a neighboring town of Tachikawa, on September 9. The following is what Gayn heard from an officer of the US occupation troops:

Long after night fall, GIs heard the sound of an approaching truck. When it was within hailing distance, one of the sentries yelled “Halt!” The truck stopped, and from it emerged a Japanese man, with a flock of young women.

Warily, they walked towards the waiting GIs. When they came close, the man stopped, bowed respectfully, swept the ground behind him with a wide, generous gesture, and said: “Compliments of the Recreation and Amusement Association!”46

At times the RAA had to confront various problems caused by GIs. Comfort stations were often visited by groups of drunken GIs in the middle of the night, after a station had closed. When they were refused entry, GIs committed abuses.

For example, on November 8, 1945, about 60 GIs came to a comfort station, Miharashi, in

i

mori district. When they found that it was closed, they went on a wild rampage, setting fire to the kitchen. At many comfort stations, GIs demanded refunds, claiming that the service was poor; others robbed the cash by holding a manager at gunpoint. Some military police who patrolled the district of comfort stations demanded “free service” almost every night.47