Love Letters of the Angels of Death

Read Love Letters of the Angels of Death Online

Authors: Jennifer Quist

Love Letters of the

Angels of Death

Copyright © 2013 Jennifer Quist

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,

for any reason or by any means without permission in writing

from the publisher.

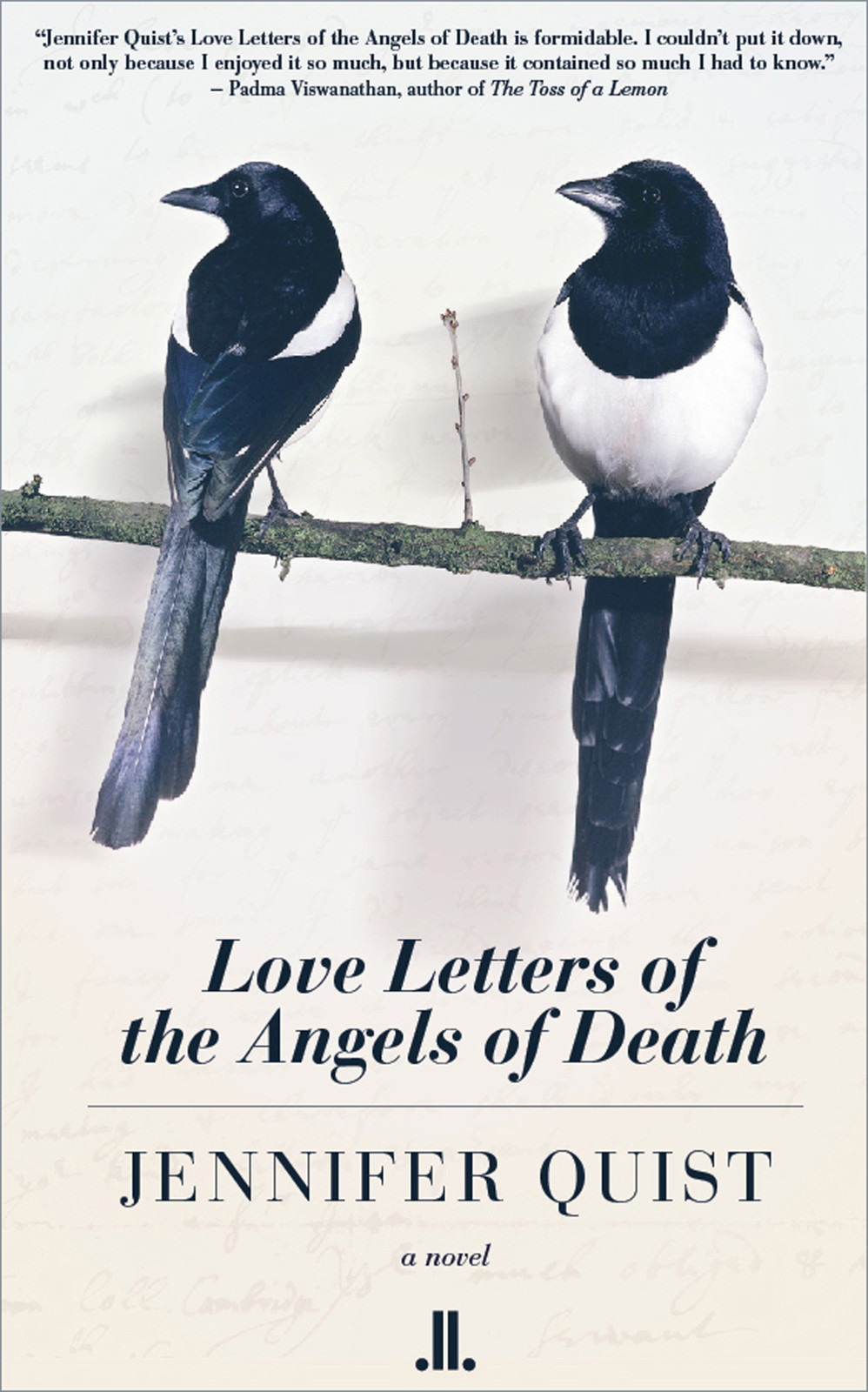

Cover design: Debbie Geltner

Cover image: Warren Photographic

Book design:

WildElement.ca

Author photo: Sara MacKenzie

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Quist, Jennifer,

author

Love letters of the angels of death / Jennifer Quist.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-927535-15-8 (pbk.).--ISBN 978-1-927535-16-5 (epub).--ISBN 978-1-927535-17-2 (mobi).--ISBN 978-1-927535-18-9 (pdf)

I. Title.

PS8633 U588 L69 2013 C813'.6 C2013-902009-8

C2013-902010-1

Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Book Printing Inc.

Legal Deposit Library and Archives Canada

et Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Linda Leith Publishing acknowledges the support of the

Canada Council for the Arts.

.ll.

Linda Leith Publishing Inc.

P.O. Box 322, Station Victoria,

Westmount, Quebec H3C 2V8 Canada

[email protected]

www.lindaleith.com

Love Letters of the

Angels of Death

JENNIFER QUIST

a novel

For Anders

Contents

One

It was only a matter of time before we found human remains. Maybe that's true for everyone. This is how it happened for us.

The Earth is jammed with dead things. Everyone knows that. But this isn't just another day of tiptoeing through jelly fish on the beach or scrubbing smashed insects off the windshield. This is different. We aren't on a nature walk. We're in a small, dark enclosure made of spongy plywood and translucent, corrugated fibreglass. Mom calls it “the veranda” because she's actually kind of funny sometimes. The veranda is hammered together around the front step of her trailer. The trailer itself is right inside the gates of the Mountain View Mobile Home Community.

If it wasn't just a rental, and if I was a better son, I might have done something to try to make this place a little less grim. But I haven't.

Right now, it's the middle of the afternoon, it's windy hot, and the wooden slab behind the screen door of Mom's trailer is bolted shut. I've got one eye closed and I'm pressing my open eye up to the crack between the door and its frame. I can't see anything â not even the thinnest line of light from inside the trailer. You are standing behind me, turned away from me to watch the driveway, still waiting for the man who rents Mom the trailer to meet us here with his morning star of dingy brass keys.

And it's early, early in another one of our pregnancies â the one we hope will be the final pregnancy of our marriage. You're at that stage where your sense of smell is more like a super power, so I step out of the way, nudging you toward the locked door, asking you to take an olfactory reading for us. But even after you sniff against the scruffy wood hard enough to make yourself cough, all you can say is, “Tobacco. Someone used to smoke out here â a lot â and I can't get past the tobacco.”

It looks like we'll have some more time before the landlord gets here, so we stand in the veranda and go down the list again â Mom's parents, ex-husbands, my sisters and brother, the hospitals, police stations, her one friend who will still talk to her after the latest pyramid sales fiasco. We name all the people who've told us they haven't seen her for days.

“The window,” you say.

I stand on the stringy, strip of quack grass â which Mom, in all earnestness, calls “the lawn” â and I watch you climb over the creosote-soaked salvaged railroad timbers and into the flowerbed outside the living room window. Mom isn't much of a gardener, so the bed is full of nothing but foxtails and variegated goutweed.

I hear you pronouncing a lame, weak curse on the vertical blinds hanging like a heavy, dirty, pleated skirt across the inside of the window. “Dang it. I can't see a dang thing.”

From the lawn, I see Mom's neighbour standing up behind the window of the trailer next door to scowl out at you and your noise. If his dusty picture window weren't sealed, he'd be able to poke a broomstick out and touch the aluminum-clad wall of Mom's trailer. Maybe you see him too â scowl and everything. Maybe that's why you curl up your hands into fists and beat on the pane of Mom's window once, twice, three, four times.

“Lin-da!”

Remember when we were first married and she asked you to call her “Mom?” You've still never done it â not even in the days before she cheerfully and accidentally called you a prostitute for only giving me three children in nine years of marriage. Luckily, by the time she said it, I'd already convinced you Mom never meant any harm, and it was best just to keep laughing at her. We laughed, all right.

I'm pretending not to see her grouchy neighbour as I beckon to you, trying to get you to step out of the flowerbed. “Come out of there. Before someone calls the police.”

You jab the glass with your index finger hard enough for me to hear the click of your fingernail. “Maybe we should be the ones calling the police and they can come smash in this window themselves. She's in there,” you say before you bend over and try to fluff up the trampled, watery goutweed.

But there's no need to call anyone. Mom's landlord is already standing in the gravel driveway, locking the doors of his pickup truck with his remote control key fob. He's come wearing faded green scrubs like doctors wear in hospitals. Only he's not a doctor. He's a veterinarian who dresses like one on days when he's working indoors, in his surgery. Aunt Marla says he owns most of the trailers here plus a bunch of other shabby little houses all over town. I guess even a tiny community like this one needs a slumlord.

From above his big yellow moustache, he looks down at you where you're still standing in his flowerbed. But he's talking to me. “Sorry about the wait. I had to finish up at my day job.”

And that's when the guilt makes its first lunge at me â like maybe I shouldn't have just stood here in the yard all this time, waiting for him to stitch up his last freshly sterilized cat belly of the day. Maybe I should have let you ram your fists through the window â or pushed right past you and crashed into the trailer myself â just to show them all that this matters.

The veterinarian slumlord calls me back as I start up the flaky wooden stairs, up into the shadow of Mom's veranda. “Hey. Since I've got the key and everything, maybe you want me to go in first.”

He's holding some kind of skeleton key between two fingers, away from the rest of the bristling mass of metal keys in his palm â like it's a scalpel, or something. And I'm staring into that hospital green he's wearing â a colour I recognize from the spectrum of disaster. You're standing behind him, on the driveway, with your throat flushed red.

I'm agreeing with him. “Oh. Yeah.” I punctuate it with a small, phony laugh, for some reason.

The landlord steps around me, in front of me, shorter than me, especially with his head bent low and his shoulders rounded as he digs at the lock with the skeleton key. You're behind me, your hand â hot from all your new pregnancy blood â pressed into the centre of my back.

The door opens and we each yell a “Linda” into the quiet, filthy home of a woman blind on years and years of diabetes denial. I walk into the bedroom where I figure she's mostly likely to be, sick in bed. The landlord moves toward the living room even though there's no sound coming from the television. And you step inside to stand on the grimy tiles between the front door and the bathroom. I hear you sniff at what the sealed windows and the old tobacco residue have kept hidden from us until now.

The smell in here â is it dirty laundry, a stagnant toilet that needs flushing, or fifty-five years of bad breath let out in a great and terrible exhale?

They are wrong when they tell you how it will be when you find the body. Everyone who has tried to imagine it but does not yet know â they are all wrong. They are wrong when they say the smell will be like nothing else. They are wrong. Because even a dead person still smells like a person.

“There she is.”

I turn to see the veterinarian trotting out of the living room â head down, shoulders pulled up toward his ears, reigning in the urge to run. And behind him, laid out on the nylon carpet, we see a scruffy grey-brown wig and a set of cheap clothes stained all over with chokecherry syrup. The veterinarian landlord is herding us backward, out the narrow entryway, back onto the veranda. He's not intimidated by an animal as large as me and without having to touch me, he forces me back against your small, hot hand.

“Yup,” he says as he pulls the front door closed behind himself, “She's dead.”

Even after all this it still feels like a mistake. I'm arguing. “Are you sure?”

Behind me, you're saying my name in a little girl's voice. “Brigs...”

The veterinarian ducks his head like he's reading his watch, and I can hear the gag in his voice as he tells me, “Yes.”

In the morning, you're not just sad. You're ashamed. “I woke up in the middle of night and got â all freaked out and scared, like an idiot.”

It is stupid, and it's too bad. But I know exactly what you mean. Our loved one has become a Halloween prop, and the grief of it feels differently in our hands than it looks in art or on the news or anywhere else.

The veterinarian landlord had dialled 9-1-1 on his cell phone and urged us not just out the door of the trailer but all the way back up the street to my Aunt Marla's house. That's where our kids and our suitcases and the long, hard task of telling and telling and telling were all waiting for us.

We were well away from the trailer park when the police and the ambulance arrived with a stretcher and a long, zippered bag. It was bad. Mom's body had been there, face down â not awake and not asleep â on the floor in front of her television long enough for her skin to break down, becoming an osmotic membrane. No matter what she used to tell people when she was selling those detoxifying foot pads from that shady herbal health distributor, only corpses have osmotic skin that can drain vital fluids directly into the outside world like a wrung out sponge. Everything inside her had been seeping out into the carpet underneath her body for what must have been days and days.

You talk to the veterinarian on the phone the morning after they take Mom's body away. He tells you he cut the worst bit of the carpet right up off the floor, hauled it to the dump with a can of gasoline, and lit the whole thing on fire. It was bad. You thank him.

One of the police officers, the vet can't help but tell you, was sick right in the potentilla bush planted at the base of the veranda. After that, the poor cop had to go sit â all humiliated and waiting â in the car. You thank the vet for that too. Mom would have enjoyed it. She never liked the cops.

And you never liked this town â the place where I was raised, the place with generations of my ancestors buried in the cemetery. “They're all talking about it now,” you say as we walk back up the block, between the sad, small houses Mom used to call “pokey.” We've made the necessary obeisance to our children, updated Aunt Marla, and now we're heading back to the Mountain View Mobile Home Community to clear out the trailer.

“This is the kind of town,” you warn me, “where we can never come again without being known as âthe ones who found the body.'”

The medical examiner has already called from the quiet of the Calgary morgue to ask me questions about Mom's medical history. I really don't know much. Mom mostly just bickered with her doctors about the “corporate medical machine,” so the information we got was never very good.

When Mom's dead-person doctor heard about her decades of diabetes and the open heart surgery and everything, she told me right away that there won't be any need for a full-blown autopsy. If we want them to give us a toxicology report we'll have to pay them ninety dollars and wait the better part of a year. For the doctor and the woozy policemen, the investigation of my mother's death is finished.

You and I are outside the trailer again. The veterinarian slumlord has left the front door unlocked and all the windows are slid wide open. The rooms are breathing out that warm, gummy stench through the folds of the pleated skirt blinds. After the wrestle with the flaming carpet, the vet has no more pity left for us. He tells us the trailer needs to be completely cleared in the next two days so it can be gutted and scorched and recovered for the use of future renters â as if this town will ever forget to keep calling this place “The Dead Lady Trailer.”

You wouldn't let me come back here alone. We leave our kids at Aunt Marla's house for a little longer while we pile Mom's books, bath towels, clothes, dishes, uneaten groceries, and old bits of yellowed computer hardware on the lawn like specimens at an archaeological dig.

The carpet and its foam underlayment are hacked away, leaving a bare, ragged rectangle on the living room floor. It's not quite like one of those crime scene chalk-outline drawings, but it's close. For the first few hours we spend inside in the trailer, we walk around the outline, reverent and ginger. But by the time we leave at the end of the day we've learned to stomp right over it, as if its edges weren't lightly streaked with dried, burgundy blood.

Outside, the neighbours are nowhere. “Look, it's turned into a ghost town out here,” you say. “Get it, Brigs â ghost town?”

“Good one. Ya kill me.”

And you hold your stomach and laugh way too loudly, flaunting our presence to all these closed doors and windows.

I don't ask you how you can bear the smell inside the trailer and why you're not sick this morning like you've been every day for the last seven weeks. Maybe it's some kind of evolutionary gift â an extraordinary override your parasympathetic nervous system accepts when it senses its own dead.

“I think I've figured out what happened,” you finally tell me. And you walk through the trailer narrating the story in the physical evidence, like a voice-over at the end of one of those Agatha Christie movies Mom used to watch on Sunday nights.

“She's sitting here, having a meal.” You stand beside the small kitchen table piled high with pulpy novels and knitting magazines, pointing out the half-eaten grilled cheese sandwich tipping off the edge of a saucer. Mom's primly zipped insulin kit sits beside it.

“And then she's sick.” You show me the splotch dried on the linoleum under the table. “So she gets herself to the bathroom.”