Jacquards' Web (8 page)

Authors: James Essinger

Charles Babbage, in a letter to John Herschel,

1

August

1814

A winter day in London, December

1839

.

It has not been a good year. With riots erupting almost every day in the countryside and towns over high food prices and low wages, many fear that England is in danger of sliding towards anarchy. By modern standards the vast majority of people in Britain are horribly poor, suffering routinely from malnutrition, illness, and despair. The small proportion of the population who are well-fed and privileged sleep uneasily in their comfortable beds, only too aware what happened in France a few decades ago.

Jacquard, resting in peace in his grave at Oullins, has been dead for five years. Queen Victoria, still only twenty, has reigned in England since June

1837

.

45

Jacquard’s Web

And now here we are at Number One Dorset Street, Charles Babbage’s London home. Babbage, forty-seven years old, is sitting at his writing-desk in his study. He takes out his pen, dips it into an inkwell, and starts to write a letter to a Parisian friend.

The particular friend Babbage is writing to as we meet him is the French astronomer and scientist, François Jean Dominique Arago. Babbage got to know Arago in Paris back in

1819

when he travelled there with John Herschel, a close companion from his Cambridge days. Babbage and Arago hit it off at once. They have been friends ever since. When Babbage corresponds with Arago he does so in English, while Arago replies in French. They both understand each other’s native languages, but prefer to express themselves in their own.

‘My dear sir,’ Babbage writes:

I am going to ask you to do me a favour.

There has arrived lately in London … a work which does the highest credit to the arts of your country. It is a piece of silk in which is woven by means of the Jacard [sic] loom a portrait of M. Jacard sitting in his workshop. It was executed in Lyons as a tribute to the memory of the discoverer of a most admirable contrivance which at once gave an almost boundless extent to the art of weaving.

It is not probable that that copy will be seen as much as it deserves and my first request is,

if

it can be purchased, that you will do me the favour to procure for me two copies and send them to Mr Henry Bulwer at the English Embassy who will forward them. If, as I fear, this beautiful production is not sold, then I rely on your friendship to procure for me

one

copy by representing in the proper quarter the circumstance which makes me anxious to possess it.

This letter is the first mention in Babbage’s surviving correspondence of the woven portrait of Jacquard—the exhibit which, the following year, he was to make a conversation piece at his Saturday soirées. Babbage was so fascinated with Jacquard and the ‘most 46

From weaving to computing

admirable contrivance’ he had invented that he asked Arago, in the same letter, to send ‘any memoir which may be published of M. Jacard’. Money was no object to Babbage, so keen was he to get what he wanted. Although he was mis-spelling Jacquard’s name, he had no misapprehension about the revolution the Jacquard loom had created in the story of technology: Whatever these things may cost, if you will mention to me the name of your banker in Paris I will gladly pay the amount into his hands and shall still be indebted to you for procuring for me objects of very great interest.

Babbage’s letter then proceeds to the hub of the matter. The Englishman explains exactly why he is so fascinated by the Frenchman’s work:

You are aware that the system of cards which Jacard invented are the

means

by which we can communicate to a very ordinary loom orders to weave

any

pattern that may be desired. Avail-ing myself of the same beautiful invention I have by similar means communicated to my Calculating Engine orders to calculate

any

formula however complicated. But I have also advanced one stage further and without making

all

the cards, I have communicated through the same means orders to follow certain

laws

in the use of those cards and thus the Calculating Engine can solve any equations, eliminate between any number of variables and perform the highest operations of analysis.

Among Charles Babbage’s many contributions to the birth of information technology, the most significant was that he spotted a way to adapt Jacquard’s punched-card programming to a completely new purpose:

mathematical calculation

.

At a technical level, Babbage really did borrow Jacquard’s idea lock, stock, and barrel. Babbage saw that just as Jacquard’s loom employed punched cards to control the action of small, narrow, circular metal rods which in turn governed the action of individual warp threads,

he himself could use the same principle to

47

Jacquard’s Web

control the positions of small, narrow, circular metal rods that would

govern the settings of cogwheels carrying out various functions in his

calculating machine.

As a result of this insight, Babbage was able to design the only machine of the entire nineteenth century that was even more complex than Jacquard’s loom.

The conceptual link Babbage made between his own work and Jacquard’s is beyond doubt one of the greatest intellectual breakthroughs in the history of human thought. It is a leap of the scientific imagination that is too easy to take for granted today, when computers and information technology are all around us, when we are so familiar with the role that computers and the Internet play in our lives, and when we use on a routine, daily basis, machines that are essentially special kinds of Jacquard looms built to weave information rather than fabric.

This is not to imply that computers would never have come about if the Jacquard loom had never existed. Computers are so useful that it is difficult to believe a technologically sophisticated society would not have invented some other machines for processing information if there had never been a Jacquard loom. But if the Jacquard loom

had

never existed, computers would certainly look and work very differently from how they look and work today.

Babbage’s Difference Engine, with which he was occupied for around twelve years, from

1821

to about

1833

, was to be an automatic cogwheel-based machine designed to calculate and print mathematical tables. Brilliantly ingenious, as it was, it still fell far short of the fully automated and versatile general mathematical machine—in effect a Victorian computer made from cogwheels—that Babbage eventually glimpsed on the most distant regions of his intellectual horizon. The precise link with Jacquard’s work does not appear to have occurred to Babbage until the mid-

1830

s, when he conceived of a much more ambitious and complex device than the Difference Engine. He later christened this new machine the Analytical Engine.

48

From weaving to computing

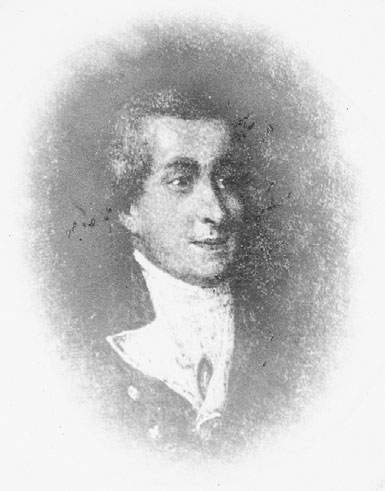

Charles Babbage at the time when he was working on the Difference Engine.

Babbage planned the programming system of the Analytical Engine to be what was essentially a direct imitation of Jacquard’s method for using punched cards to ‘program’ his loom. Babbage borrowed Jacquard’s method to control every single aspect of the Analytical Engine’s operation, with the cards intended to be used to input data and to make his cogwheel computer carry out specified functions. Like modern computers, the Analytical Engine was designed to have a memory (Babbage called this the

‘store’) and a processor (the ‘mill’, as Babbage named it). Babbage, a perfect gentleman when it came to acknowledging his sources, freely admitted his debt to Jacquard. He was only one of Jacquard’s disciples, but he was the most brilliant, the most industrious, and the one who was least willing to take no for an answer.

49

Jacquard’s Web

The man whose mind sparked a flaming suspension bridge between the weaving industry and computing was born in London on

26

December

1791

. His father, Benjamin Babbage, was a wealthy goldsmith and banker. The two professions were then closely linked; it was a small step for customers who were buying gold and jewellery from a goldsmith to use the safes in the goldsmith’s offices to store all their valuables.

The Babbages had been well-established since the late seventeenth century in Totnes, a small town in the county of Devon in the south-west of England. The very first documentary mention of the Babbage family there dates from

12

November

1600

, when a William Babbage, who died in

1633

, is recorded as having married one Elinora Ashellaye. Later, on

18

April

1628

, a Roger

‘Babbidge’ is listed as a payer of rates. Benjamin was the latest in a long line of Babbages who distinguished themselves in commerce. Charles Babbage’s grandfather, also a successful goldsmith and also called Benjamin, had been mayor of Totnes in

1754

.

Totnes today is a busy, friendly little market town, especially popular with people living New Age and alternative lifestyles. Its population has remained unchanged at about

6000

since the end of the eighteenth century, when it was extremely wealthy by the standards of the day. The historical prosperity of Totnes derived from wool sheared from the backs of the innumerable sheep that spent their lives munching the grass of the meadows on the hills that ripple around the town. This wool was woven by hand into an inexpensive, coarse, long-lasting woollen cloth called kersey.

There was a huge demand for this cloth throughout Britain and abroad for workmen’s breeches and trousers.

Charles Babbage

1753

’s father, Benjamin, born in

, gradually

built up his activities in the town and the surrounding district. He did not open a bank, but traded more informally, lending out sums, transacting business under his own name, and acting as an agent for some London banks. Business was excellent.

Yet by the start of the

1790

s, the Totnes cloth trade was visibly waning. Machines powered by steam were making an 50

From weaving to computing

impact on weaving and on all aspects of fabric-making. The new form of power provided what seemed at the time to be close to unlimited energy. The steam engine also offered the enormous advantage that it was no longer necessary for mills and factories to be located near running water for operating water-wheels.

Coal was the fuel of the future, and in this new industrial world Totnes was at a grave disadvantage, for Devon had no coal at all.

The Industrial Revolution was gathering momentum. Totnes was being left behind.

A wily fellow by nature, Benjamin was quick to spot the significance of the new developments. He rapidly made plans to transfer his business activities to London, a radical move indeed in those days, when the vast majority of the population lived out their lives in the village or town where they had been born. It has been said that many people who lived in villages at this time, and for another century or so, never met more than about seventy-five people in their entire lives.

Benjamin moved to London in

1791

, taking with him his wife, Betty, whom he had married the year before. He had first-class business contacts in the capital. Benjamin eventually became a partner of Praeds Bank in London, probably one of the banks for which he had acted on an agency basis back in Devon.

His timing for his move to London was highly fortuitous, yet Benjamin had always made his own luck, and there was really nothing accidental about his success in London. He chose to migrate to the great capital—then easily the largest city in the world—at a time when there was a huge increase in the demand for credit, mainly caused by the burgeoning Industrial Revolution. The banking business was literally a golden opportunity for lenders who could keep their heads and who had the skill to distinguish good credit risks from bad. Benjamin possessed that skill.

As the novels of the time were wont to put it—he ‘prospered exceedingly’.

The only surviving portrait of Benjamin shows a man with a rather jovial expression, and the look of having a precise under-51