Jacquards' Web (27 page)

Authors: James Essinger

Once the machines were developed and installed, Watson chased his engineers back into customers’ premises again to deal with any problems customers might be having. Making the customer happy and eager to spend more was Watson’s most fervently held credo.

The clash of Watson’s and Hollerith’s personalities was a classical example of a brash, energetic, visionary newcomer confronting a staid traditionalist. Watson wanted to create a new organization that would combine world-beating products with world-beating expertise at selling them. This was a different dimension compared to the formal, technically accomplished, but limited and hidebound ways that were habitual to Hollerith.

Such clashes are seen frequently in business. There is rarely an exception to the rule that it is the younger, more commercially 190

The birth of IBM

visionary protagonist who wins. Not that it was much of a battle in the case of Watson and Hollerith. Hollerith was rich, tired, not especially healthy and past his prime. Watson was younger, hungry, and he had the world before him.

Faced with the choice between having to step in line and becoming a sort of senior acolyte of Watson or washing his hands of his whole involvement with C-T-R, Hollerith took the inevitable step. He resigned from the Board of the Tabulating Machine Company on

15

December

1914

, two weeks after an ill-tempered discussion with Watson in which the younger man had made plain his intention to build a major sales organization out of C-T-R. Hollerith was, among other things, opposed to doing this. He had cautioned Watson that ‘too many men are out for orders in this business … regardless of the consequences’. But Watson did not care about the consequences. He wanted the orders.

Not unlike Jacquard himself, Hollerith spent the rest of his life in luxury and comfort, working farm land he had purchased, and gaining much enjoyment from the simple country life and the company of his family. In his old age he enjoyed sending his friends vast boxes containing produce he had grown on his farm.

Sometimes the boxes contained forty or fifty pounds of vege-tables.

Despite his differences with Watson, Hollerith continued to offer Watson advice. Watson magnanimously respected and valued this. He often invited Hollerith to discuss important issues with senior staff of C-T-R and on occasion to address factory-workers. No doubt Watson found it easier to do this now that Hollerith no longer threatened his power base. Hollerith gracefully continued to make suggestions for new types of machine.

Watson invariably acted on these ideas, perfectly aware, with becoming modesty, that he himself would always remain a mere novice when it came to inventing revolutionary tabulation technology. He even arranged for a song about Hollerith to be written and sung at C-T-R social events. This, sung to the tune of the 191

Jacquard’s Web

then-popular Laurel and Hardy song ‘On the Trail of the Lone-some Pine’ (which, rather bizarrely, was to enjoy another spell of popularity in

1975

), went:

Herman Hollerith is a man of honour

What he has done is beyond compare

To the wide world he has been the donor

Of an invention very rare.

His praises we all gladly sing.

His results make him outclass a king.

Facts from factors he has made a business.

From the years good things to him bring.

Not a lyrical masterpiece, perhaps, but one could hardly deny that its heart was in the right place.

Watson, like any great leader who sees himself as surfing the leading wave of destiny, had a keen sense of history. He believed that in order to build for the future, an organization should have a sense of its own past. He urged Hollerith to save his letters and papers and wrote to him saying that there was surely a very interesting story to be told ‘about the tabulating machine and the man who invented it’. He evidently hoped that Hollerith might tell this story, or at least find someone to whom he could tell it, but neither of these things happened. That had to wait.

In

1924

, in recognition of the fact that the tabulating machines were making a far greater contribution to C-T-R’s profits than any other product, Thomas Watson changed the company’s name to International Business Machines Corporation Inc, or IBM for short. Another three-letter acronym, and one that has become perhaps the most famous commercial acronym in the world.

The intimate relationship between the Jacquard loom and Hollerith’s tabulation machines, and the simple fact that these machines helped IBM develop into a global business, compel us to the irresistible conclusion that IBM had its origins in Jacquard’s endeavours in Revolutionary France. And indeed IBM

is, indeed, a direct descendant of the work that went on in 192

The birth of IBM

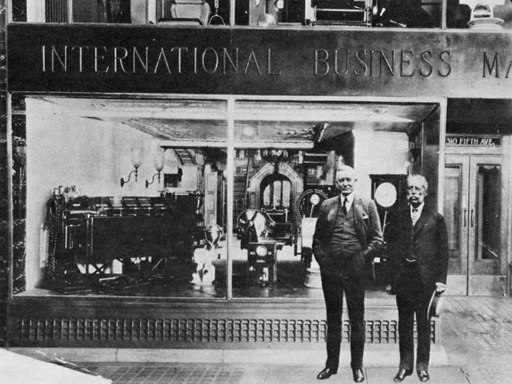

Thomas Watson and Charles Flint: two proud and successful capitalists standing to attention.

Jacquard’s workshop during the last years of the eighteenth century and the first years of the nineteenth.

The world of people such as Charles Ranlegh Flint and Thomas Watson may, on the face it, seem a long way from that of Joseph-Marie Jacquard. But in fact the two worlds are connected by the clearest strand of logic. Any successful invention gives rise to improved versions of itself that will, in due course, foster the creation of an industry. Like religions, inventions tend to be created by lone geniuses but are typically developed and furthered by practical-minded, even ruthless, realists. The evolution of the Jacquard loom followed this pattern precisely. Few people were more practical-minded, ruthless, and realistic than Flint and Watson.

193

Jacquard’s Web

By

1928

, with annual sales of about $

20

million (worth about $

300

million today), IBM was the fourth largest office machine supplier in the world. It still lagged behind Remington Rand, which made typewriters, and behind NCR and the Burroughs Adding Machine Company, but IBM was engaged on a process of dramatic growth, and was rapidly catching up with its bigger rivals.

Meanwhile, Herman Hollerith spent most of his time running his farm. On

17

November

1929

, after only a short illness at the end of a retirement which had been almost entirely free of ill health, he died of heart failure. He was sixty-nine years old. He was already on the way to slipping from the consciousness of the commercial world. His machines, those extraordinary looms that wove information, were helping all types of organization—

public and private—to win mastery over that very information.

As for IBM, it had now been founded, and the right person was at its helm. The stage was set for the Jacquard loom to start weaving the future.

194

1 ❚ 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ❚ 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 ❚ ❚ 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 ❚ 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4

5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 ❚ 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5

6 6 6 ❚ 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6

7 ❚ 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7

8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 ❚ 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8

9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 ❚ 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ❚ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Most organisations, when they would dream of the exaltations of the present, roll their eyes backward. The International Business Machines Corporation has beheld no past so golden as the present. The face of Providence is shining upon it, and clouds are parted to make way for it. Marching onward as to war, it has skirted the slough of depression and averted the quicksands of false booms. Save for a few lulls that may be described as breathing spells, its growth has been strong and steady.

From a report in

Fortune

magazine,

1940

Herman Hollerith never liked the way he had been pressurized by his first government customers to rent out his machines rather than sell them. The governments preferred to do this because they had no reason to own the machines permanently, but Hollerith would have much preferred to have sold his machines outright.

195

Jacquard’s Web

When Hollerith started making headway into the commercial sector, he again tried to sell his machines to his customers.

But it turned out that commercial organizations, too, wanted to rent the tabulators. They knew how expert Hollerith was at improving his machines. They were confident that renting them from him rather than buying them outright meant they could always insist on being supplied with state-of-the-art machines.

Meanwhile, Hollerith had little choice but to take the older machines back from his clients and melt them down.

By the time IBM was created, the system of renting tabulators to customers rather than selling them was taken for granted.

During prosperous times it was, admittedly, by no means an ideal way of doing business: IBM would have much preferred its customers to have bought the older tabulators

and

the ones that superseded them. But when economic conditions worsened, as they did in the

1930

s, the way Hollerith had been forced to do business not only saved IBM from likely disaster, but—really quite by chance—helped to catapult it to success.

The point was that even during the Depression, existing IBM customers, who would not have been able to afford to buy tabulators outright, found that they could still just about afford to rent them. The customers wanted to keep the machines if possible; they still needed them, and so the rental system was a blessing to them. As it was for IBM, which continued to win rental income from all its machines that were out with customers.

There was also an attractive cost factor. The rental on an IBM

tabulator repaid the machine’s manufacturing costs in about three years. After this period virtually all the income from the machine was pure profit.

Another major income stream came from sales of blank cards that would be punched and processed by the tabulators. IBM

enjoyed very much the same near-monopolistic control of the supply of these cards that Hollerith had enjoyed twenty years earlier. The cards had to be manufactured with great precision on special paper stock; most of IBM’s competitors found it impossi-196

The Thomas Watson phenomenon

ble to make blank cards to a similar quality of specification. Some, investing considerable sums, did manage to reach IBM’s quality standard, but they did not enjoy the same economies of scale as IBM did and so could not compete with IBM on price.

The demand for punched cards remained high because once a card had been punched, it could not be re-punched to store other information. It could, of course, be re-used, but only as the repository of data already on it. IBM’s clients had to punch new cards every single time they wanted to input new information.

Many of IBM’s biggest users required millions of cards every year.

This was because new cards would usually be required not only for each new customer but even for each new transaction a new or existing customer made. Even modestly sized organizations would typically use tens or hundreds of thousands of cards annually; large organizations would indeed use millions.

The figures speak for themselves. During the

1930

s, an otherwise wretched decade for capitalism, IBM sold about three billion cards a year in the United States alone. Revenue from cards accounted for only about ten per cent of IBM’s annual income but approximately thirty-five per cent of its profit. It is amusing to record that one of the most technologically advanced organizations in the world at the time was deriving so much of its profit from selling cardboard cards, but—as Thomas Watson might have said—good business is where you find it.

A dangerous competitor to Hollerith and later IBM in the field of tabulation machine manufacture was, as we have seen, the engineer James Powers. In

1911

he formed his business interests into the Powers Accounting Machine Company. In

1927

this company was acquired by typewriter manufacturer Remington Rand, but Powers remained at the helm of the tabulation machine operation. The capital that Remington Rand brought to the party gave Powers an unprecedented level of strength to increase the scale of its competition with IBM.

During the

1930

s both organizations fought vigorously against each other to offer the fastest and most reliable tabulation 197

Jacquard’s Web

machines to the market. Yet IBM always had the better of the game. Its machines were known for being more reliable, more technologically advanced and better maintained than those sold by Powers. It was also widely recognized that IBM’s salesmen were more devoted, dynamic, and deadly competitive than those employed by Powers and knew more about the machines they were selling. This technical expertise was substantially the result of Watson’s creation of a special IBM training school at Endicott, New York.