It Takes a Village (4 page)

Read It Takes a Village Online

Authors: Hillary Rodham Clinton

I understand that nostalgia. I feel it myself when the world seems too much to take. There were many good things about our way of life back then. But in reality, our past was not so picture-perfect. Ask African-American children who grew up in a segregated society, or immigrants who struggled to survive in sweatshops and tenements, or women whose life choices were circumscribed and whose work was underpaid. Ask those who grew up in the picture-perfect houses about the secrets and desperation they sometimes concealed.

The longing we feel for “the way things used to be” obscures not only the reality of earlier times but the larger settings in which the family finds itself today, as it struggles with the effects of broken homes, discrimination, economic downturns, urbanization, consumerism, and technology. Whenever someone bemoans the loss of “family values,” I think about the changes that began when I was a child in the 1950s which have dramatically altered the way we live, much as the automobile reshaped the lives of an earlier generation.

Nobody predicted the magnitude of the changes, good and bad, that the technological revolution would bring. The advent of television is the most obvious instance. We got our first set in 1951. It was a fascinating novelty, and my father complained that we would watch television all day, starting with 6:00

A

.

M

. mass for shut-ins, if he would let us. But television was not nearly the presence in families' lives or the influence on their values that it has become.

Another big innovation was fast-food restaurants. We lived near the very first McDonald's franchise in America, in Des Plaines, Illinois. I can remember how the sign announcing the number of hamburgers sold was changed from week to week. But most of us still ate dinner at home, at the same time every night, facing each other at the table and “minding our manners.” Going out to eatâeven for a hamburgerâwas a special, memorable occasion. Today I know adults so busy with their jobs that they cannot tell you the last time they had a family meal that included their kidsâand excluded the television set.

Starting in the 1950s, we also began to move around more. When President Eisenhower championed the country's massive federal highway system and airport-building program for national defense reasons, few people imagined how those roads and airports would come to influence family life. I took my first plane ride when I was in high school; my nephews flew across the country as infants.

New roads permitted more people to commute to work in cities from suburbs like mine and to settle even farther away. The construction of highways broke up some existing neighborhoods and sapped the economic life of others. Daily visits with cousins and grandparents became rarer as businesses began transferring workers all over the country. We were among the lucky who could choose to sink roots and stay in one place.

Advances in telecommunications were just starting then too. The houses in my neighborhood typically had one phone downstairs and one upstairs, with only one line. Children had to limit their time on the phone and use it in a public part of the house. We were not slaves to our phones; if someone called and we were out, they would call back if it was important. No one had an answering machine. And there were no cellular phones to interrupt what we were doing or to distract us from those around us.

In many ways, families like mine had the best of both worldsâthe prosperity generated by new technology and mass production, without the conflicts and anxiety these developments inflicted on households and individuals within a few decades. We could attain a comfortable standard of living on a single income, typically the father's. Even with a limited education, people could find work and expect to keep it until retirement, without worrying about being rendered obsolete by automation or information technology. A third of the work force belonged to unions, and the gap between what workers and their managers were paid seemed like a fordable stream.

Most of all, we felt that we were part of the same enterprise. It may have been the cold war that brought us together, but together was how we felt. When President Eisenhower urged us to study more math and science after the Soviet Sputnik was launched, we believed that our President and our country needed us to do that. President Kennedy's call to public service inspired many of us too. We were not subjected to a daily diet of second-guessing and cynicism about the motives and actions of every leader and institution.

It is difficult, for those of us who grew up in an era that appeared to embody so many ideals people yearn for now, to acknowledge that it unwittingly set in motion the very forces that sometimes make us feel isolated within our own households and communities today. So alienated do we feel from the larger society at times that we cannot imagine the village existing in any form anymore. But each era gives birth to the village of the next generation.

Like our families, the culture we inherit is a product largely of events and decisions we had little hand in choosing. Not that the culture is our destiny, any more than the family is: families have thrived in the harshest conditions, and individuals have survived in the harshest families. But the society is our context; we do not exist in a vacuum. Even now, in ways we cannot yet feel or recognize, the village in which our children will raise their children is taking shape. It is up to us to think carefully about what kind of legacy we want to leave them.

If I could say just one thing to parents, it would be simply

that a child needs someone who believes in him

no matter what he does.

ALICE KELIHER

M

OST OF

the people I knew growing up had families remarkably like mine. I did not have a single close friend, from kindergarten through high school, whose parents were divorced. But there was someone I knew very well who was the child of divorce: my mother.

My mother was born in Chicago in 1919, when her mother was only fifteen and her father just seventeen. A sister followed five years later, but both parents were too young for the responsibilities of raising children, and they decided they no longer wished to be married. When my mother was only eight years old and her sister barely three, her father sent them alone by train to Los Angeles to live with his parents, who were immigrants from England.

When my mother first told me how she cared for her sister during the three-day journey, I was incredulous. After I became a mother myself, I was furious that any child, even in the safer 1920s, would be treated like that.

To this day, my mother paints a vivid picture of living in southern California seventy years ago. She describes the smells of the orange groves she walked through on the way to school and the excitement of taking a streetcar to the beach. But these carefree memories were shrouded in harshness. Her grandmother was a severe and arbitrary disciplinarian who berated her constantly, and her grandfather all but ignored her. Her father was an infrequent visitor, and her mother vanished from her life for ten years.

Yet my mother was not without allies and a “village” to support her. A kind teacher noticed that she was often without milk money and bought an extra carton of milk every day, which she gave my mother, claiming she herself was too full to drink it. A great-aunt, Belle, gave my mother gifts and from time to time intervened to protect her from her grandmother's ridicule and rigidities.

When she was fourteen, my mother moved out of her grandparents' home and went to work taking care of a family's children in exchange for room and board. The position enabled her to attend high school, but not to participate in after-school activities. Every morning, she was up very early to prepare breakfast for the children, and every night she stayed up long after they had gone to sleep, to do her homework. The family appreciated her way with children, saw her true worth, and encouraged her to finish high school. The mother, a college graduate, gave her books to read, challenged her mind, and emphasized how important it was to get a good education. She also provided a role model of what a wife, mother, and homemaker could be.

How I wish I could have met Aunt Belle and the woman who employed my mother. I would tell them of my gratitude for the nurturance and encouragement that helped my mother overcome the distrust and disappointment she met with in her own family. They healed her of what could have been lifelong wounds. And yet, to a great extent, my mother's character took shape in response to the hardships she experienced in her early years. From those challenges came her strong sense of social justice and her respect for all people, regardless of status or background. From them, too, came her passion for learning, and for the joy that knowledge brings.

After high school, my mother moved back to Chicago and took a series of secretarial jobs. At one of them, she met and began dating my father. While my father was in the navy, my mother continued working. When the war ended, my father started his own business. My mother helped him with his work and raised the three of us.

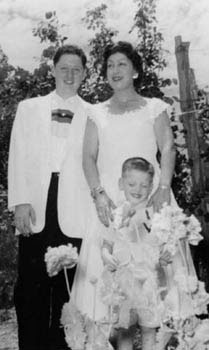

I found myself thinking about my mother's story when I first met my husband at law school, in 1971. Like her, Bill had grown up in circumstances that were less than ideal. His mother, the late Virginia Kelley, one of the great originals of our time, grew up in Hope, Arkansas, as an only child. After high school, she studied nursing, and during the war she met Bill's father, William Blythe of Texas. They were married in September 1943, just before he left for the battlefields of Europe.

When he got back, in 1945, he and Virginia moved to Chicago. I've often wondered whether Virginia Kelley and my mother might have crossed paths there, perhaps while standing in line at Marshall Field's big department store downtown.

Virginia became pregnant and went back to Hope to be among family and friends for her baby's birth. Her husband planned to join her as soon as he got their new apartment ready. He left Chicago to drive to Arkansas, and on the dark, rainy night of May 17, 1946, he had a fatal car crash outside Sikeston, Missouri.

Virginia, although devastated by the loss of her husband, was determined to do her best to provide for her baby. William Jefferson Blythe arrived three months later, on August 19, the birthday of Virginia's father, James Eldridge Cassidy. Virginia and he went home from the hospital to live with her parents, who shared responsibility for raising him during his first six years. Despite their differences, Virginia and her strong-willed mother, Edith Valeria Grisham Cassidy, were united in one thingâtheir devotion to Bill.

Wanting to provide a better life for her child, Virginia left Hope to attend a program in New Orleans that would grant her a nurse-anesthetist's degree. That meant leaving Bill in the care of her parents for a year. Virginia often said that being away from her son almost killed her. One of Bill's earliest memories was taking the train with his grandmother to visit Virginia for the weekend. As they were leaving on Sunday, he remembers seeing his mother drop to her knees, crying, by the side of the tracks.

Bill's family were people of modest means, but they understood how important a child's early years were for his developmentâintellectually, socially, and emotionally. His grandmother, who had earned a degree in nursing by taking correspondence courses, quizzed him on his numbers, using playing cards taped around his high chair. She read aloud to him every day and encouraged him to learn to read before he started kindergarten.

His grandfather, who had only finished grade school, spent lots of time with Bill, taking him along on errands and to the little grocery store he ran, always stopping to visit with friends along the way. Bill surely owes much of his gregarious nature to those early days of chatting his way through town.

Although I never met Bill's grandparents, I know that their profound and engaging love for him helped to fill the hole left by the father he never knew and to protect against the pain he would later face.

Bill's life changed dramatically when he was four. Virginia married Roger Clinton, a local car dealer, and they moved into their own small house in Hope. Almost from the beginning, the marriage was anything but hopeful. Roger had a tendency to drink too much, becoming a mean and bullying drunk. The story of the abuse and violence Virginia suffered at his hands is told in her warm and funny autobiography,

Leading with My Heart.

I asked Virginia once why she stayed married to Roger. She explained that she was raised to believe marriage was for life and divorce was wrong. And, she added, most of the timeâwhen he wasn't drunkâRoger could be sweet and a lot of fun. Even so, she did divorce him in 1962, when his alcoholic rages became too much for her to bear. But three months later, feeling sorry for him and believing his promises to change his ways, she remarried him, against Bill's advice. Bill, now larger than his stepfather, warned Roger in no uncertain terms never to hit or threaten his mother again.

Roger and Virginia had moved to the larger town of Hot Springs, Arkansas, when Bill was seven. Although Virginia could no longer call on her parents for daily help and felt uncomfortable relying on Roger, there was a clan of Clinton uncles, aunts, and cousins who provided family support for Bill through the years. Virginia also hired a neighbor, Mrs. Walters, to help care for Bill and, later, his brother, Roger, while she was at work. Even with a full-time job and the ongoing tensions in her marriage, Virginia saw to it that their home became a haven for neighborhood kids, who gathered after school to shoot baskets, play music or cards, or just talk. When she got home from work, she joined right in.

Because Bill was old enough to distance himself, physically and emotionally, from his stepfather's behavior, he was able to weather the tensions of his home life. He also developed relationships with other adults. Some doctors his mother worked with took a special interest in him and spent time counseling him. The teachers and band directors he studied under encouraged his academic and musical talents. And no matter how hard times were, his mother got up every morning to do her job and set an example of self-discipline and resilience that spoke louder than words.

The human family assumes many forms and always has. The Clinton household didn't fit the conventional model. But it would be presumptuous of anyone to say it was not a legitimate family or that it lacked “family values.” Bill never doubted that his mother and the other adults in his life supported him with all their hearts. His family had its problems. So did mine, and, I imagine, yours. But as psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner reminds us, “The one most important thing kids need to help them survive in this world is someone who's crazy about them.” Bill and I were both fortunate to have that.

That kind of love can make up for a lot, but it can't remedy everything. Virginia loved her second son, Roger junior, who was born in 1957, every bit as deeply as she loved Bill. But as much as she loved him, she could not shield him from the worsening effects of his father's chronic alcoholism. The problems he experienced growing up were typical of the difficulties children undergo when the structure of the family is unstable, either within a two-parent family or because of divorce.

There is no set formula for parenting success. Many single-parent, stepparent, and “blended” families do a fine job raising children. But in general their task is harder. And these days parents are less likely to have readily available support from extended family or a close-knit community. There are fewer Aunt Belles, grandparents, and other relatives close by, and many of us no longer feel free to ask a neighbor to lend a hand or an ear.

The instability of American households poses great risks to the healthy development of children. The divorce rate has been falling slowly, but for a high proportion of marriages, “till death do us part” means “until the going gets rough.” And there has been an explosion in the number of children born out of wedlock, from one in twenty in 1960 to one in four today.

More than anyone else, children bear the brunt of such massive social transitions. The confusion and turmoil that divorce and out-of-wedlock births cause in children's lives is well documented. The results of the National Survey of Children, which followed the lives of a group of seven- to eleven-year-olds for more than a decade, and other recent studies demonstrate convincingly that while many adults claim to have benefited from divorce and single parenthood, most children have not.

Children living with one parent or in stepfamilies are two to three times as likely to have emotional and behavioral problems as children living in two-parent families. Children of single-parent families are more likely to drop out of high school, become pregnant as teenagers, abuse drugs, behave violently, become entangled with the law. A parent's remarriage often does not seem to better the odds.

Further, the rise in divorce and out-of-wedlock births has contributed heavily to the tragic increase in the number of American children in poverty, currently one in five. And while divorce often improves the economic condition of men, who are rarely awarded custody, it nearly always results in a decline in the standard of living for the custodial parentâgenerally the motherâand the children.

The disappearance of fathers from children's daily lives, because of out-of-wedlock births and divorce, has other, less tangible consequences. Girls are more likely to respond with depression and inhibited behavior, whereas boys are more likely to drop out of school and to have academic or behavioral problems. As Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan warned more than thirty years ago, the absence of fathers in the lives of childrenâespecially boysâleads to increased rates of violence and aggressiveness, as well as a general loss of the civilizing influence marriage and responsible parenthood historically provide any society.

A child's prayer is used as the logo for the Children's Defense Fund: “Dear Lord, be good to me. The sea is so wide and my boat is so small.” Children without fathers, or whose parents float in and out of their lives after divorce, are the most precarious little boats in the most turbulent seas.

Many who protest loudly against welfare, gay rights, and other perceived threats to “family values” have been uncharacteristically silent about divorce. One does not have to agree with all the remarks of former Secretary of Education William Bennett to welcome his acknowledgment before the Christian Coalition that divorce is hard on children: “In terms of damage to the children of America, you cannot compare what the homosexual movementâ¦has done to what divorce has done to this society. In terms of the consequences to children, it is not even close.”

Perhaps the most compelling evidence comes from the mouths of children themselves. I recently received a letter from a fifteen-year-old boy in Louisiana whose parents had divorced. “I've come to distrust you adults and the legal system in this country,” he wrote. “It seems to me that you adults do a lot of talking and nothing more.” He went on to describe what the breakup is doing to his family, as a unit and as individuals. “I try hard not to become an angry, bitter young man towards my father and the system,” he told me. “But it is not fair to me or my mom that she has to be both mother and father to me and my little brother. It makes no sense to me.” It should make no sense to any of us.