Read It Takes a Village Online

Authors: Hillary Rodham Clinton

It Takes a Village (29 page)

The Golden Rule does not mean that gold shall rule.

BARBARA REYNOLDS

M

y father distrusted both big business and big government. When I was growing up, he never tired of quoting President Eisenhower's warning against the military-industrial complex and the dangers of concentrated, unaccountable power in anyone's hands. I thought of him during a trip I made to South America in October 1995, when I happened to hear a reference to the words of an earlier President, Theodore Roosevelt. I was to give a speech to students and faculty at the University of Chile in Santiago. When the rector of the university introduced me, he referred to remarks that Roosevelt had made in the same hall eighty-two years before. The former President, he said, had warned against the excesses of unchecked corporate power.

Intrigued, I tracked down a copy of Roosevelt's speech and was struck by how relevant his message remains today:

By allowing, with no control, this concentration of enormous enterprises in the hands of a fewâ¦many evils have arisenâ¦. We must recognize that the great corporations have established themselves, and that we must control and regulate them, so that big business does not obtain advantages at the expense of the smaller. Moreover, we must insist on the principles of cooperation and the mutual sharing by employer and employee in the gains produced, so that the future prosperity of the great corporations is divided in the most equitable way among all those who participate in creating it.

Roosevelt's words reflected the popular view that would dominate much of this century. As the private sector grew, people assumed that the excesses of unbridled competition had to be restrained by government. As a result, consumers have been protected by antitrust laws, pure food and drug laws, labeling, and other consumer protection measures; investors have been protected by securities legislation; workers have been protected by laws governing child labor, wages and hours, pensions, workers' compensation, and occupational safety and health; and the community at large has been protected by clean air and water standards, chemical right-to-know laws, and other environmental safeguards.

Doubtless, mistakes were made in drafting some of these laws and in writing and applying the regulations that put them into effect. But on balance, it is hard to quarrel with the results. Over the course of the century, our environment has become cleaner, we have become healthier, our workers safer, our financial markets stronger. Now our economy, still the world's most powerful and productive, is on a roll again, with small-business formation, exports, and the stock market all at record levels, more than seven and a half million new jobs created in less than three years, and the combined rates of unemployment and inflation at a twenty-seven-year low.

In an era in which it has become fashionable to blame many of our nation's ills on government, however, our public debate seldom turns to the impact of economic forces on American families and children. Those who do raise the question are likely to be accused of insufficient devotion to the free market system. Yet if we care about family values, we have to be concerned about what happens to those values in the marketplace.

Like my father, I support capitalism and the free market system. But I also know that every human endeavor is vulnerable to error, incompetence, corruption, and the abuse of power. To paraphrase Winston Churchill's famous aphorism about democracy, capitalism is the worst possible form of an economyâexcept for all the alternatives.

There is built-in tension in a free market system like ours, because the same forces that make an economy strongâthe drive to satisfy consumers' demands by maximizing productivity and profitabilityâcan adversely affect the workers and families who are, after all, those very consumers. While we want to encourage competition and innovationâhallmarks of American capitalismâwe need to be aware of the individual and social costs of business decisions. In every era, society must strike the right balance between the freedom businesses need to compete for a market share and to make profits and the preservation of family and community values. If either is undermined, the consequences will end up costing us all more in the long term, materially and otherwise, than we can possibly gain in the short term.

In this book I have talked about the responsibilities of individuals and institutions for the future of our children and the village they will inherit. No segment of society has a more significant influence on the nature of that legacy than business. We live in an era of what political scientist Edward Luttwak calls “turbo-charged” capitalism, which is characterized by intense competition; breathtaking technological changes; global financial, information, and entertainment markets; constant corporate restructuring; and relatively less public control and influence over the private economy.

This combination of changed circumstances poses new problems for families and communities, and for the children who grow up in them. Business affects us powerfully as consumers, as workers, as investors, and, more broadly, as citizens of the society it helps to create and as inhabitants of the environment it has a strong hand in shaping. Our circumstances therefore require new and thoughtful responses from every segment of society, particularly from business.

Â

O

UR ECONOMY

grows as it gives consumers more and better products to choose from, at competitive prices. On the whole, this system has been a boon to us, not only allowing us to live comfortably but providing more Americans with jobs. But one of the conditions of the consumer culture is that it relies upon human insecurities to create aspirations that can be satisfied only by the purchase of some product or service. If all of us said today, “Okay, I have enough stuff. From now on I will buy only the bare necessities,” that would be a disaster for our economy. But spurred on by cultural messages that encourage us to feel dissatisfied with what we have and that equate success with consumptionâmessages fueled by the advertisements that constantly bombard usâwe face the far more likely danger of allowing greed to overshadow moderation, restraint, and the stability that comes from saving and investing for the future rather than satisfying short-term desires.

The threat is greatest to our children, who will inherit that future and the values that shape it. “As a society,” writes David Walsh in

Selling Out America's Children,

“we Americans of the late twentieth century are sacrificing our children at the altar of financial gain,” and, in Walsh's phrase, to the lure of “adver-teasing.” Those of us who believe in the free market system should worry about what we are in danger of becoming: a throwaway society sustained on a diet of unrealizable fantasies, a society in which peopleâespecially childrenâdefine self-worth in terms of what they have today and can buy tomorrow.

Walsh documents the careful calculationâand hundreds of millions of dollarsâthat go into advertising campaigns directed at children, whose desire for instant gratification and lack of sophistication make them easy targets. Children parked in front of the television for hours on end are particularly susceptible, and advertisers know it. After the Federal Communications Commission repealed regulations that limited the amount of time that could be devoted to commercials during children's television shows in 1984, the number of commercials again increased, and program-length commercialsâshows that revolve around toy-based charactersâexploded.

The Children's Television Act passed by Congress in 1990 again set limits on commercial time during children's programming, but compliance has not always been strictly enforced, although the FCC is trying. “Kids today,” observes FCC chairman Reed Hundt, “can identify more cereals than Presidents.” Nor is the drumbeat to buy, buy, buy confined to commercials; advertising permeates children's lives. Even their sports heroes have become walking (and slam-dunking) advertisements for everything from Nikes to Pepsis to Big Macs.

Mass consumerism and “adver-teasing” have parents competing with multinational corporations not only for their children's values and beliefs but for their health. According to one study, Joe Camel, the cartoon mascot of Camel cigarettes, is now as recognizable to six-year-olds as Mickey Mouse. Cigarette brand names have become affixed to virtually every professional sport, from soccer to skiing to sailing. If you doubt that tobacco companies target children as prospective consumers, ask yourself what gets three thousand American children to start smoking on any given day, or talk to Dave Goerlitz, an actor who appeared in commercials for Winston cigarettes for seven years, until he became so disgusted by the company's blatant attempts to lure children that he left the business and joined an antismoking crusade. Or take a look at the previously secret documents from Philip Morris, which produces two out of every three cigarettes American children smoke, that U.S. Representative Henry Waxman of California read into the

Congressional Record

in July 1995. Among the revelations was that the company, as Waxman put it, “studies third-graders to determine if hyperactive children are a potential market for cigarettes.”

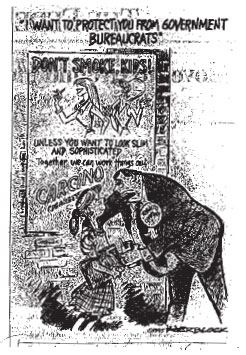

In cases where children are directly and seriously endangered by products, the government can and should step in, as the President has done in his proposal to have the Food and Drug Administration restrict children's access to cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, curtail cigarette advertising that appeals to them, and require tobacco companies to fund an educational campaign designed to counter the message that smoking is “cool.” (Predictably, the tobacco companies are spending millions of dollars to fight the proposal through legal action in the courts and through an advertising campaign against “government bureaucrats.”)

But government is a partner to, not a substitute for, adult leadership and good citizenship. Parents must become more willing to stand up to consumer pressures from advertisers and from their own children. They can resist the impulse to “prove” their love by showering children with things they do not need and give them precious time and attention instead. They can make a moral statement to their children and to manufacturers by refusing to buy products that promote gratuitous violence, sexual degradation, or plain bad taste. In the summer of 1995, clothing designer Calvin Klein withdrew an advertising campaign targeted at teenagers that featured young models in sexually suggestive poses after consumers objected.

Copyright 1995 by Herblock in

The Washington Post.

If parents do not take a stand, how can we expect children to resist the consumer culture's message that style is more important than substance? We can measure its potential for destruction in the young lives already lost to murder over a ski jacket or a set of fancy new hubcaps. Parents need help from the village to counteract and to curtail the force of this message. The broadcasters and publishers who provide time and space to advertisers must exercise greater restraint and better judgment. Business must work with government and families to find ways of balancing the interests of industry with the interests of children.

Â

T

HE CONSUMER

culture's assault on values adds to the pressures families are under in today's fast-changing economy. Most of us remember a time when business was an anchor in our communities. After World War II, when America had about 40 percent of the world's wealth and only 6 percent of its population, our nation enjoyed an economic boom in which businesses were expected to produce goods and services of high quality, not only for the purpose of bringing in profits for stockholders but also to create the jobs and higher incomes that would build the middle class. After all, if no one had jobs or incomes, who would buy the goods and services that businesses were producing?

In recent years, however, long-established expectations about doing business have given way under the pressures of the modern economy. Too many companies, especially large ones, are driven more and more narrowly by the need to ensure that investors get good quarterly returns and to justify executives' high salaries. Too often, this means that they view most employees as costs, not investments, and that they expend less and less concern on job training, employee profit sharing, family-friendly policies, shared decision making, or even fair pay raises that share with workersânot to mention their families and communitiesâgains from productivity and profits. Even workers' jobs may be sacrificed as executives seek short-term profits by “downsizing” or “outsourcing” (farming out to independent contractors work previously done in-house) or moving production to countries where wages are lower and environmental and other regulations less stringent. Instead of “We're all in this together,” the message from the top is frequently “You're on your own.”