It Takes a Village (24 page)

Read It Takes a Village Online

Authors: Hillary Rodham Clinton

“This is real, America,” she said. “We ask you the government, and you the employer, to help us, the working people, to make it work. We can't do it alone.”

She is right. As a nation, we must make child care a priority and begin to value the important work of raising strong, healthy, and happy children.

Children are likely to live up to what you believe of them.

LADY BIRD JOHNSON

I

have never met a stupid child, though I've met plenty of children whom adults insist on calling “stupid” when the children don't perform in a way that conforms to adult expectations.

I remember a six-year-old girl I tutored in reading at an elementary school in Little Rock. I'll call her Mary. She lived in a tiny house with six siblings, her parents, and an assortment of other relatives, who came and went unpredictably. There was so much commotion in the evenings that she was rarely able to sleep for longer than a few hours, and she always looked tired. She seemed uncomfortable talking, but she didn't want to read, either. Sometimes her eyelids would droop and she would lay her head on the desk.

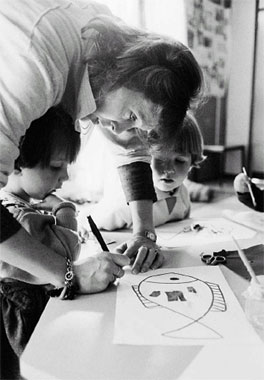

One day, desperate for a way to hold her attention, I asked Mary if she liked to draw. Her brown eyes lit up and she nodded eagerly. Her colored-pencil drawings of people and animals were technically advanced and rich in detail. Awkward as she was with words, Mary communicated vividly through her art. Her pictures of a small house crowded with many people and lacking space for her to draw or to play provided us with a way to begin talking about her life. When I complimented her on them, though, she repeated what other adults must have said to her: The drawings were just silly “baby” stuff and not very good.

When her teacher observed what we were doing, she cautioned me that my purpose was to help Mary learn to read, not to play. I suggested that encouraging Mary to express herself in her drawings and then helping her to write stories about what they conveyed could lead her to reading. But the teacher could only see that Mary and I had failed at our assigned task, which was to read stories in the class workbooks.

Mary was obviously intelligent, but her intelligence was expressed in the pictures she drew and not by trying to read from a printed page. Yet her artistic interest and talent were not being praised at home or in school. It wasn't surprising that she often seemed withdrawn or unhappy. How could she not notice that her talents were ignored, even penalized? It does not take long for children like Mary, whose intelligence is expressed in a way that is not customarily recognized or appreciated, to lose a sense of how valuable their particular gifts are, and, along with it, their confidence and sense of self.

When this happens, teachers, parents, and other adults often write them off as “slow” or “unmotivated” and come to expect less of them in the way of academic performance. Tragically, the children are thus deprived of the opportunity to master the basic skills they will need to realize their particular gifts. This is a loss not only to them but to the entire village, which could benefit from all our talents.

In his 1983 book,

Frames of Mind

, Howard Gardner outlined the theories about multiple intelligence that he had formulated while working with gifted children and children who had suffered brain damage. He discovered that the loss of certain mental capacities, such as language ability, was accompanied by an enhancement of others, such as visual or musical abilities. These findings prompted Gardner to explore how parts of the brain seem to promote different abilities. He uncovered what he describes as the capacity people have to express themselves through various forms of intelligence.

Even within the same family, it's easy to see that different children are good at different things. From very early on, some seem to be drawn to words and learning from books, although the abstract, logical reasoning mathematics requires may come less easily to them. Other children excel at math, because their minds travel most easily in the worlds of numbers and symbols, but they may have difficulty expressing themselves in words.

Verbal and mathematical abilities stand children in good stead in most classrooms. Other kinds of intelligence may go unrecognized. Children who think in visual images may not thrive when limited to words and symbols. An early knack for music, like my husband's, might be ignored if it is not accompanied by more conventional skills. So might the strong intuitive skills that allow people to read the moods and temperament of others. We have all known children who seemed to think with their bodiesâwho can rapidly learn a new sport, for exampleâand yet seem restless and uncomfortable when they are forced to sit still at a desk. The brilliant choreographer Martha Graham once said, “If I could say it, I wouldn't have to dance it.” Yet rather than celebrate our children's multiple forms of intelligence, too often we elevate one form over another or caricature kids accordingly, labeling them “jocks” or “nerds.”

Howard Gardner's list of intelligences takes into account verbal, mathematical, visual, physical, and musical intelligences as well as psychological skills like the ability to understand and interact well with others. These forms of intelligence are not mutually exclusive. Every one of us has all of them to some degree. Their particular constellation may determine not only what we are good at but how we learnâif we are given the encouragement and opportunity to develop them.

Whatever the range of intelligences includes, it is increasingly clear that standard IQ tests capture only a fraction of it. The tests were originally designed to measure only the aptitudes that fall within Gardner's first two types of intelligence, verbal and mathematical. Yet much classroom work engages only that part of a child's potential. Schools often categorize children's intelligence according to their performance on IQ and other narrowly conceived tests and adjust their encouragement and expectations accordingly. Even “slow” children are quick to catch on to the categories schools have put them into, and learn a simple equation: If adults don't think I can achieve, I can't and I won't.

The philosopher Nelson Goodman suggests that we would do well to learn to ask

how

rather than

whether

someone is smart. That question would shift the emphasis to helping individuals realize their potential, rather than whether they have potential in the first place. The main point I want to make here is that virtually all children can learn and develop more than their parents, teachers, or the rest of the village often believe. This has great implications for how we approach our children's educations.

One of the striking differences international studies have repeatedly turned up between American parents and students and their counterparts in other countries, particularly in Asia, is the greater weight our culture currently gives to innate ability, as opposed to effort, in academic success. I don't know all the reasons for this preoccupation, which seems to be linked to an obsession with IQ tests and other means of labeling people, but some possible explanations are not particularly flattering to us.

Believing in innate ability is a handy excuse for us. Too tired to read to a child or enforce rules on TV-watching or phone use? Too preoccupied to seek out extra help for a child who needs more practice with math or a foreign language? Why bother, if none of that really makes much of a difference anyway? More concerned with how a daughter looks than whether she's reading at grade level? More interested in a son's jump shot than in how he conjugates verbs? If that's what gets our attention, you can bet it's what kids will think is important too. But how can we parents see the connection between effort and appearance, or between effort and athletic prowess, but not between effort and academic success?

The bell curve lets the rest of us off the hook too. What's the sense of reforming schools, especially if it costs any money? What is the point of figuring out how to tailor teaching to the unique ways children learn? Why puzzle over what they should learn, and why bother to articulate it to them? Cream will rise to the top no matter what we do, so let nature take its course and forget about nurture.

If we are permitted to write off whole groups of kids because of their racial or ethnic or economic backgrounds, then the occasional academic shooting star will be seen as a fluke. And when whole groups of kids succeed despite the odds, like the poor Hispanic high school students Jaime Escalante coached to succeed on the Advanced Placement calculus examination, their success can be ascribed to a unique brand of charismatic teaching and motivation that can't be replicated anywhere else.

I began to work on behalf of education reform in Arkansas in 1983, when my husband asked me to chair a committee that would make recommendations for improving Arkansas's education system. That was also the year that “A Nation at Risk,” the landmark report about our schools, was issued. I couldn't begin to describe in a single chapter all the effort since then that has gone into promoting preschool and kindergarten programs, raising academic standards, establishing accountability, professionalizing teaching conditions, improving vocational and technical education, and many other changes. But after a dozen years of involvement in education reform, I'm convinced that the biggest obstacles many students face in learning are the low expectations we have of them and their schools.

I've mentioned the impact President Eisenhower's post-Sputnik call for higher math and science performance had on my generation. Performance standards were upgraded; new classroom equipment was purchased. Our parents and teachers demanded more from us. Nearly forty years later, though, education is more important to success in the global village than ever. Now we have no clear and immediate enemy to frighten us into improving education for our own children; we have to do it for ourselves. But the starting point is the same: High expectations begin at home.

Â

M

Y PARENTS

made learning part of our daily activities, from storytelling and reading aloud to discussing current events at the dinner table to calculating earned run averages for Little League pitchers. They taught me and my brothers in all sorts of informal ways before we started school, and they continued teaching us in partnership with our teachers at school.

When I was in fourth grade, I was having trouble with arithmetic. My father said he would help me if I got up as early as he did each morning. The house was cold, because the furnace was turned off when we went to bed. I would sit shivering at the kitchen table as the house slowly warmed up and my father drilled me on multiplication tables and long division.

Some parents do not easily assume the role of teacher. They may lack the confidence, be unwilling to devote the time, or simply not know, for example, that reading aloud to babies and toddlers is the single most important activity we can do with children to ensure that they will read well in school. But the village has found ways to help parents start teaching children when it counts most, in the preschool years.

In Arkansas, I introduced a program that had been developed in Israel. Called HIPPYâthe Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youngstersâit works like this: A staff member recruited from the community comes into the home once a week and role-plays with the parent (usually the mother), demonstrating for her how she can work with her child to stimulate cognitive development. Along with special activity packets, the program employs common household objects to illustrate concepts. For example, a spoon and a fork might be used to demonstrate differences in shape or sharpness, or the volume control on the TV might be turned up and down to teach the concepts of loud and soft. The material in the activity packets, designed for parents who may not read well themselves, is outlined in straightforward fifteen-minute daily lesson plans arranged in a developmental sequence. The usual starting age is four, and most children participate for two years. Some programs add a third year, so children can begin the program at the age of three.

When we brought HIPPY into rural areas and housing projects in Arkansas, a number of educators and others did not believe that parents who had not finished high school were up to the task of teaching their children. Many of the parents doubted their own abilities. One mother whose home I visited told me she had always known she was supposed to put food on the table and a roof over her children's heads, but no one had ever told her before that she was supposed to be her son's first teacher.

Not only did the program help kids get jump-started in the right direction; it also gave the parents a boost in self-confidence. Many of them became interested in learning for themselves as well as for their children, going back to school to get a high school equivalency degree or even starting college. This is a particularly important development, because researchers cite a mother's level of education as one of the key factors in determining whether her children do well in school. It stands to reason that when a mother furthers her own learning, she becomes more engaged in her child's.

There are similarâand similarly successfulâefforts going on elsewhere, such as the Parents as Teachers (PAT) program started in Missouri, which also uses home visits to coach parents on preparing children for school.

The importance of early learning is also one of the driving ideas behind Head Start, the thirty-year-old federally funded preschool education program that has consistently helped to prepare disadvantaged children for school. But Head Start doesn't reach children until they are four, when we now know from research that many of them are already behind their peers. So when Congress reauthorized Head Start in 1994, at the President's recommendation it established Early Head Start to target low-income families with infants and toddlers.

So far, however, Head Start reaches only about 750,000 of the estimated two million children who need it, and Early Head Start is just getting under way. Despite the proven success of investments like Head Start, it and many other preventive programs are caught in the battle over federal budget priorities. Our nation can afford to invest in early childhood education and balance the budget. There are few more important investments at the federal, state, or local level than programs focused on helping parents to develop the confidence and skills to teach young children.