It Chooses You (16 page)

I felt like Miley Cyrus was speaking directly to me through Lenette, and she was being very clear — she wanted me to keep the faith. I read Dina’s Popeye T-shirt, I YAM WHAT I YAM, and I felt that I too was what I was. I was a writer, and my characters, Sophie and Jason, were right here with me. In fact, they

were

me, both of them. Was it possible that Jason read the

PennySaver

? I knew for a fact that he did, because the movie was set in LA and everyone in LA, real or fictional, gets the

PennySaver

with their mail. It was so obvious, there all along, the invisible bridge — Jason wasn’t selling trees, he was buying things through the classifieds. He was meeting strangers, just the way I was, and it was transforming him and uniting him with humanity. He would stand in a living room just like this living room, and listen to someone like Lenette sing. We probably wouldn’t be able to afford the rights to the Miley Cyrus song, but who knew? Now was no time to think small. I tried to imagine who would play Dina. Or Ron. Or… Domingo. The thought was offensive. No, clearly these people would have to play themselves. We thanked Dina and I said goodbye, knowing that it wasn’t really goodbye. I wanted to wink at her or give her some kind of indication that she would soon be starring in a major motion picture, but I restrained myself.

It was like the scene in

Pollock

where Marcia Gay Harden looks at Ed Harris’s first splatter painting and says, soberly, “You’ve broken it wide open, Pollock,” and you know she’s right because those splatter paintings are worth a kabillion dollars in real life now. Marcia Gay Harden wasn’t with me as I drove home from Sun Valley, so I had to say it, soberly, to myself —

You’ve broken it wide open, July

— and then I had to look exhausted and unaware of the greatness I’d stumbled into, the way Ed Harris does, and then I had to be the woman watching the movie based on my life, someone who might have been born today but who thirty-five years from now would know that history had proved the brilliance of Jason buying things through the

PennySaver

. She shivered a little, this woman who would be thirty-five in thirty-five years; tears jumped to her eyes as she watched the reenactment of this pivotal moment in film history. It didn’t even matter that she wasn’t a fan of my work — I’m not a huge Pollock fan. It’s just the way Marcia says it. I whispered it again:

You’ve broken it wide open, Pollock.

I’d had a similarly groundbreaking revelation twenty-five years earlier, when I was nine. The epiphany came one night, just before I fell asleep: I would make an entire city out of cereal boxes. I’d collect the boxes over months and I’d paint them, hundreds of them, stores and streets and houses and freeways, forming a whole little world that would be an accurate representation of my hometown, Berkeley (although I wasn’t totally married to the specifics yet — it might be better to make it more of an Everytown, USA, since geography wasn’t my strong suit). The city would take up the whole basement floor and I would bring special people down there, to the basement, and turn on the lights and, boom, their minds would be blown to pieces. After passionately nursing this idea for about an hour, I suddenly had another idea: No I wouldn’t. Of course I wouldn’t make an entire city out of cereal boxes in the basement. The moment I had this second thought, I knew this was the real one. But I also felt certain that the thought itself was the only thing that had stopped me, like a witch’s curse — or, no, like the witch

hunters

, the small-minded, fearful Local Authorities.

From then on to this very moment, I had done everything I could to avoid them, but after almost three superstitious decades I’d come to realize that the Local Authorities are always there, inside and outside, and they get most riled up when I begin to change. Each time I feel something new, the Local Authorities step in and gently encourage me to burn myself alive.

So now I called Dina immediately, before the second thought could come. She took the idea of an audition in stride, as if it were the usual outcome of trying to sell your hair dryer. The next day I drove back to the FEMA-like encampment with Alfred and a video camera and suggested that we begin by reenacting our meeting the day before. I would knock on the door, she would let me in, she would tell me about the hair dryer. Get it? Yep. Okay, let’s try it.

An unexpected thing happened when Dina opened the door, and it wasn’t the unexpectedly wonderful thing I was expecting. She stopped using any contractions or colloquialisms —

isn’t

became

is not

,

yeah

became

yes

. Her arms suddenly moved like a museum docent’s or a stewardess’s, gesturing formally this way and that. Every living thing had mysteriously died the second we turned the camera on. I tried in vain to start over, to loosen the air, but after a while I felt out of line, almost rude. Eventually I let go of my plan and asked if Lenette might sing for us again. Lenette performed a rap she had written herself, titled “La La.” It was very, very catchy. I had it in my head for days. But Dina and Lenette would not be in the movie, and this was a very bad idea, casting people through the

PennySaver

. Whoever was responsible for such a bad idea should be burned at the stake.

—

$1

—

—

And so I went to Joe’s, knowing that he would be the last person I interviewed. The PennySaver mission had been a worthy escape, but it felt different now that I had tried to make it useful and failed so completely. It was a little bit silly and definitely frivolous, given how little time I had left in every sense. I’d gone from high-high to low-low, and now I was just trying not to disappoint the man selling the fronts of Christmas cards.

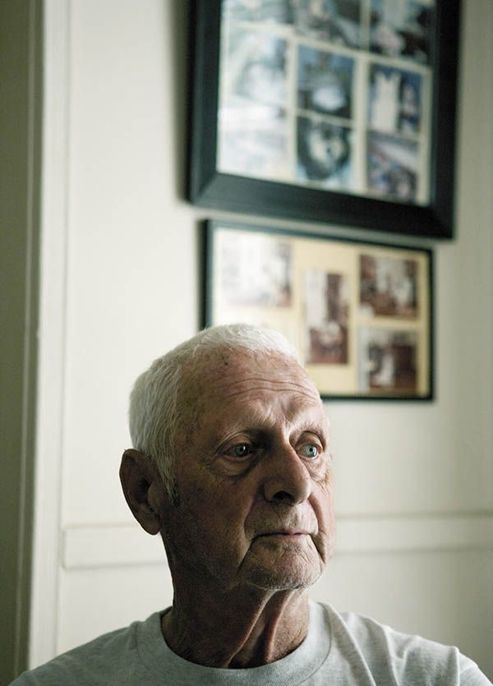

Joe lived near the Burbank airport; a plane roared over my head as I rang the doorbell.

Joe: What’s this, a machine gun?

Miranda: That’s a camera. And just to get it out of the way, here’s your payment for the interview.

Joe: Yeah, we could really use it, I’ll tell you. We’re living on about nine hundred dollars a month from Social Security, so it’s kind of tight, the money is, and as you get older you need more pills and more medical care. I never went to a doctor the first fifty years I was born, but after then you’re falling apart. I just turned eighty-one about three weeks ago.

Miranda: How long have you lived here?

Joe: It’ll be thirty-nine years in August that we’ve been here. Moved here in 1970.

Miranda: Where are you from originally?

Joe: Chicago.

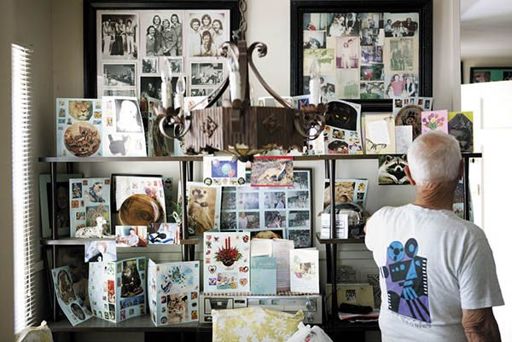

The house was very clean and worn; each piece of furniture was tidily being used to its very end. The walls were covered with a lifetime’s worth of pet photos, cat and dogs, but there were no actual pets in the house. Out of the corner of my eye I could see shelves filled with what looked like handmade cards.

Miranda: And what was your work?

Joe: Well, I was a painter, a painting job, and I turned into a contractor when I came out here, and I was doing real good.

Miranda: So a painter of, like, houses?

Joe: Houses, yeah.

Miranda: What are all these cards? Did you make these?

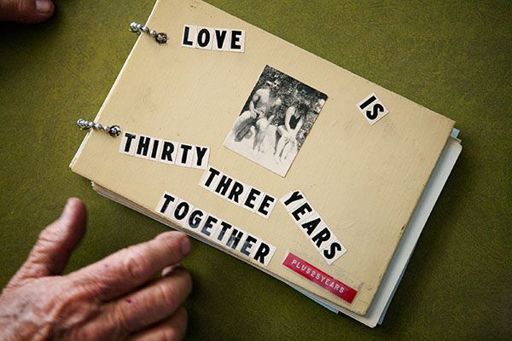

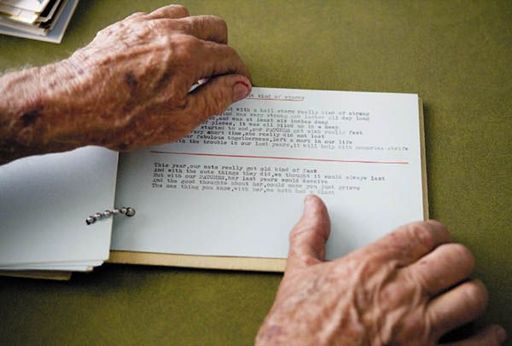

Joe: Yeah, I make cards for my wife. See, what I do is I make them out of paper like this, and I cut these pictures out of magazines and papers. Then I make the poem here, then I make limericks. But I don’t know if you want to read some of them — they’re pretty dirty.

Miranda: Oh, really? Can you read me one?

Joe: All right, if you want. Let me find a good one.

There once was this beauty from the city

And her boobs were so big it was a pity

Her boyfriend marveled about her nice chest

Then he proceeded to lunge for her breast

Soon his mouth was jammed with her left titty.

Miranda: Very nice rhymes.

Joe: The first and second and fifth lines gotta rhyme, and then the third and fourth lines rhyme. Say for instance the word

sex

. Well, there’s only maybe two words that it can rhyme with, so I have to go through and dig back in the library.

Miranda: And does she like them? What’s her reaction?

Joe: Oh, yeah, she likes them. A couple of years ago she started wanting to make one for me, so she’s got a couple of little ones up there like these. I make her nine cards a year. Mother’s Day and our anniversary, and the fourth of July is the day I met her, in 1948, so that’s the last card I just made. And I make Christmas and New Year’s, and Easter, and Valentine’s Day. We just celebrated our sixty-second anniversary — we’ve been married sixty-two years.