Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (20 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

9

. Secker and Warburg, 1949, and Penguin Books, 1962. It is from this edition that all passages quoted in this article have been drawn.

10

. Whoever described the Countess of Kent as an ‘authoress’ in the D.N.B. cannot have examined the book.

RECEIPTS

Here are two brief recipes, interesting, although not typical ones (since most of these are too long for quotation here), from the Kent medical collection, followed by two from

The True Gentlewoman

.

To take away Hoarseness

‘Take a Turnip, cut a hole in the top of it and fill it up with brown sugar-candy, and so roast it in the embers and eat it with Butter.’

A Strengthening Meat

‘Take Potato roots, roast them or bake them, then pill [peel] them, and slice them into a dish, put to it lumps of raw Marrow [i.e. bone-marrow] and a few Currants, a little whole Mace, and sweeten it with sugar to your taste, and so eat it instead of buttered Parsnips.’

To boil a Capon or Chicken in White broth with Almonds

‘Boil your Capon as in the other, then take Almonds, and blanch them and beat them very small, putting in sometimes some of your broth to keep them from oiling; when they are beaten small

enough, put as much of the uppermost broth to them as will serve to cover the Capon, then strain it, and wring out the substance clear, then season it as before [i.e. with grated Nutmeg, Sugar, and Salt], and serve it with marrow on it.’

How to make a Florentine

‘Take the Kidney of a Loin of Veal, or the wing of a Capon, or the leg of a Rabbet, mince any of these small, with the Kidney of a Loin of Mutton; if it be not fat enough, then season it with Cloves, Mace, Nutmegs and Sugar, Cream, Currans, Eggs and Rosewater, mingle these four together and put them into a dish between two sheets of paste, then close it, and cut the paste round by the brim of the dish, then cut it round about like Virginal Keys, then turn up one, and let the other lie, then pink it, bake it, scrape on sugar, and serve it.’

This last recipe is particularly interesting for the manner in which the pastry is cut (I have made it. It does indeed resemble virginal keys) and because Robert May has a picture (

p. 265

of the 1685 edition) of just such a pie – although not the recipe. The edition of May’s book,

The Accomplisht Cook

, in which two hundred additional and very interesting Figures, as he calls them, first appeared, was published in 1664, a long while after that of

The True Gentlewoman

, so it looks as though May borrowed the idea from her book – I have not seen it described in any other work – forgetting to insert the recipe, or finding the obviously left-over wing of capon or leg of rabbit beneath his style of cooking. His two Florentine recipes are predictably more complex and on a grander scale.

One more slender connecting link between May and the

True Gentlewoman

are the recipes for black tart stuff and yellow tart stuff which appear in both books but not in others of the period which I have seen. These pie fillings are, respectively, mixtures of raisins and prunes cooked and sieved to a purée, and a rich egg custard sweetened with sugar and sack. May has three variations on the black one [

see

the recipe on

page 59

], one of them very similar to the

True Gentlewoman

’s. Their yellow tart stuffs differ in that the lady’s calls for 24 eggs and a quart of milk, May’s for 12 eggs and a quart of cream. May also has red, white, and green tart stuffs, made from quinces, cherries, red currants, red

gooseberries, damsons, pippins, barberries, raspberries for the red ones; for the green, spinach, peas, sorrel, green apricots, peaches, green nectarines, green gooseberries, green plums, the juice of green wheat; for the white, just whites of eggs and cream sweetened with sack and sugar, and perfumed with rose-water, musk and ambergris.

Did May borrow the black and yellow mixtures from the

True Gentlewoman

and then concoct his green, red and white mixtures? Useless speculation. But not entirely irrelevant, for it has to be said that although May’s book will always be immensely interesting, the man himself was a great boaster and a bit of a fraud, who slammed French cooks and cooking and nearly all the books written by his predecessors and contemporaries, at the same time coolly admitting that he had helped himself from the best French, Italian and Spanish works, although he was careful not to say on what a wholesale scale he had lifted, appropriating for example the entire chapter on egg cookery from La Varenne’s

Le Pastissier François

. As for English books, the only one for which he had a good word was the

Queen’s Closet

published in 1655 by Nathaniel Brook, by coincidence his own original publisher.

It is a curious point that while the modest little Kent book ran into twenty-one editions and lasted for over half a century, May’s far grander and more important one, with its beautiful illustrations, ran into no more than five editions and had a life of only twenty-five years. And, unjustly, May was ignored by the compilers of the D.N.B.

Petits Propos Culinaires

, 1979

Quiche Lorraine

It was in the classrooms of upper-crust English cookery schools of twenty years ago that the ex-debs of the time learned to make great thick open pies crammed with asparagus tips, prawns, mushrooms, crab-meat, olives, chunks of ham, all embedded in custard as often as not solidified with cheese. In directors’ dining-rooms and later in expensive delicatessens and in the new-style London wine bars they dubbed those creations ‘quiches’. It was libel really,

but the British have never been too particular in such matters. As far as imported foreign specialities are concerned it’s the name they fancy, the substance isn’t of much account. It’s not difficult to see why the girls picked on those hefty pies as their

pièces de résistance

, and called them quiches. The name is catchy and they hadn’t been taught what the real thing was.

The Constance Spry quiche lorraine recipe published in the Cordon Bleu cookery school bible in 1956 has cheese and onions in it: a young girl I knew attending classes given by a respected Kensington teacher circa 1960 was taught to make quiches with a filling of evaporated milk and processed Cheddar; so when the time came the young women who graduated into the genteeler areas of catering found that they could get away with putting anything they chose into a pastry shell and calling it a quiche.

In 1966, via Penguin paperback, Julia Child’s

Mastering the Art of French Cooking

began to reach a massive British audience. From that formidably detailed manual, cookery students now learned that a quiche was ‘an open-faced tart’, that it was ‘practically foolproof’, that ‘you can invent your own, anything combined with eggs, poured into a pastry shell’. Mrs Child and her collaborators had provided a sound enough recipe – classic they called it – for quiche lorraine, its filling just eggs, cream, bacon. No cheese, they emphasised. Few British readers can have paid attention to that instruction. They didn’t want to, any more than they had wanted to when in my own

French Provincial Cooking

(1960) and

French Country Cooking

(1952) I had published recipes for the regional quiche lorraine which didn’t call for cheese. What the catering girls went for was the licence provided by Mrs Child to print the word quiche in connection with any and every open-faced tart – if that’s the only alternative description one sees why it was discarded – filled with any one of fifty-seven different combinations of fish, fowl, vegetable, cured pork and cheese.

Those confections were immensely convenient. The ingredients for the fillings were as variable and interchangeable as anyone could wish. As Mrs Child had promised, quiches were all but foolproof. They could be made in the cook’s own time, on her own premises, they were easy to transport, safe to warm up, saleable in wedges, and extraordinarily profitable. Those little bits and pieces encased in good stout pastry walls are a lot cheaper

to buy than the double cream and eggs which are the main ingredients of the traditional quiche of Lorraine. No wonder that that one was quickly rejected as a profit-making proposition for wine bars and delicatessens. Besides, like so many seemingly easy dishes, the simple version of quiche lorraine is quite tricky to get right. It needs accurate timing. It isn’t too successful when reheated. Anyway, British cooks tend to mistrust simple recipes calling only for a minimum number of ingredients. They suspect there’s something missing. So they supply the lack.

In 1932, Marcel Boulestin, whose cookery books were by then well known to connoisseurs of good food, came up with a quiche lorraine recipe. It appeared in a little volume called

Savouries and hors-d’oeuvre

(reprinted in 1956), and figured among the hot hors d’oeuvre. Boulestin’s recipe called for flaky pastry and a filling composed of a tumbler of cream, a quarter pound of grated Gruyère, and just one beaten egg. A few pieces of bacon chopped fine were optional. Not a compulsive recipe. The cheese, like the flaky pastry, was quite alien to the rustic nature of the original,

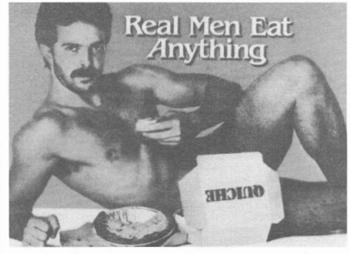

This postcard made Elizabeth laugh, and she kept it for many years

but it probably appealed to English cooks. The anachronisms had undoubtedly come via Paris chefs.

As far back as 1870 Jules Gouffé, head panjandrum of the kitchens at the very grand Paris Jockey Club, had published an appropriately sumptuous and imposing

Livre de pâtisserie

in which he had re-interpreted the quiche lorraine according to the lights of the grande cuisine of the period. Gouffé spelled the word ‘kiche’ and made its base of puff pastry instead of the piece of leavened dough which formed the mainstay of the original. For fillings for his ‘kiches’ Gouffé gave several variations. One called for parmesan cheese, one was sweetened with sugar and scented with orange flower water, one was perfectly straightforward, consisting of butter, eggs and cream in generous quantities and without redundant frills. Gouffé – who had served his apprenticeship with Carême and whose brother Alphonse was in charge of Queen Victoria’s pastry kitchens – had all the same taken the first step in the Parisianisation of the primitive galette or quiche as it used to be made in the villages of Lorraine before the Franco-Prussian war of 1870. But Jules Gouffé can hardly be held responsible for the fate which overtook the quiche a hundred years after his book was published at the hands, not of his own culinary heirs, but at those of Albion’s cooking daughters.

It’s too late now to restore the ravaged image of the quiche as we know it in British take-aways and wine bars, ‘made up of egg, cheese, milk and ham and seasoned with herbs, part-cooked and ready to eat after 20 to 30 minutes in an oven’. No comment, but here, for the record, is a description of how the quiche lorraine was made in its days of innocence.

The recipe was recorded by the French académicien André Theuriet and contributed by him to a wonderful treasury of recipes and food lore put together by his friend Edmond Richardin – both men were natives of Lorraine – and published in 1904 under the title

L’Art du bien manger

. ‘The quiche or galette lorraine was the delight of my childhood,’ Theuriet wrote, remembering back some forty or more years. ‘You take a piece of bread dough, you roll it out as thin as a two sous piece and you spread it out very carefully in a shallow fluted toleware tart tin, previously dusted with flour. On this round surface you arrange, chequer-board fashion, fresh diced butter. This preliminary effected, in a salad bowl beat an appropriate number of eggs, adding a bowl of thick ripe cream of the previous day’s skimming. When this filling

is thoroughly blended and just sufficiently salted, pour it over the prepared dough. Now carry your galette to the blazing oven of the neighbourhood bakery. Leave it five minutes, no longer. It will emerge puffed up, golden, blistered, alluring, filling the house with its savoury aroma. Eat it scalding hot, with it drink one of the light pineau wines from Lorraine and you will appreciate what good cheer means.’

Indeed, yes. But I suggest we keep that from the pizza houses or next thing we know it’ll be pizza lorraine and back we’ll be with that old dream topping of Carnation and Kraft.

To be fair to the gentrifiers of the quiche, even when Jules Gouffé came on the scene the basic bread dough version already had a gone-up-in-the-world local rival. Jules Renauld, historian of drinking and eating customs in Lorraine and author of

Les Hostelains et Taverniers de Nancy

, published in 1875, described the quiche lorraine as being a very thin round of ordinary tart pastry spread with an equally spare dressing of cream and eggs no thicker than a sheet of paper laid over the pastry. The quiche had been known in Lorraine, he claimed, for at least 300 years. As evidence he cited a payment for quiches supplied by Charles Duke of Lorraine’s household steward for his master’s table on 1 March 1586. So quiches were then accepted as Lenten fare.