Indian Innovators (13 page)

This is not all. You can interact with real and virtual objects at the same time. For instance, you are having a one- to-one video chat with one of your friends, and his 2D picture is on the screen. Or picture this – another friend enters the room and stands behind your computer screen. You will see only that part of him/her that is not being covered by the computer. On the computer screen, you will see only your chat friend. Now imagine a system that lets you see your chat friend in 3D, as if he is standing right in front of you, like a real person. Now, when another friend enters the room, it appears that there are two persons in the room, rather than just one real person. So, the virtual object merges into the real environment. Thus, this technology blurs the difference between the real and virtual worlds.”

Ganesh adds that VORWIS is very different from Google Glasses. “VORWIS would enable us to share what we are seeing live through our eyes, in real time with our friends. It is much like what the Google Glass Project promises, but much better. With Google Glasses, one interacts via buttons placed on the sides of the glasses; while in our case, the interaction is via gestures. Plus, we are not too sure whether Google even plans to have virtual 3D objects. Their offering is based on conventional 2D displays.

Google Glasses were announced in early 2012. We conceptualized our idea in 2010 and have been working independent of any other group, developing our own technology.

The project consists of three parts: Visualization of 3D objects, Interaction with 3D objects and Sharing of 3D objects.”

Ganesh and Pragyan share the current status of the project and future plans. “We have completed work on the interaction part and are currently working on the sharing part. Sharing would enable collaboration; for instance, several friends can together solve the Rubik’s cube and any change made by any of them would reflect on everybody’s screen. Also, the technology can interact with other digital devices such as smartphones. So, you can get 3D map navigation on your glasses by using the 3G internet connection on your phone.

For the visualization part, we need to work with hardware (VRD) vendors like Microvision and that would come next. Meanwhile, we are trying to start with the patenting process.

Our parents do not really understand what we are doing, but they think it must be something really good because it sounds quite hi-tech. They have an idea that we may not apply for campus placements, but they have been quite supportive.”

With the path charted out so clearly and so early, these two geniuses are all set to leave an indelible mark on the world of computing.

For the Innovator in You

“We strongly believe in the Law of Attraction – if your desire is strong and you work hard enough to achieve it, then you start attracting the result you wish for.

For those who are still in college, we suggest that if you have a great idea, do not wait. College is probably the best time and place to try out your idea, because there is hardly any pressure from the fear of failure and ample institutional support is available.

If you are smart enough to do something innovative, then you will definitely find a job waiting for you, if you ever need it.”

Ahmed Khan, Managing Director, KK Plastic Waste Management

Road Construction using Plastic Waste

For the generation that grew up learning that plastic waste is an ecological disaster, Ahmed Khan is a pleasant surprise. In an age where governments across the world have failed to find a solution to the plastic waste menace, he seems to have found the perfect answer.

Ahmed Khan was born to a school-teacher father and homemaker mother and grew up in a village in the Mandya district of Karnataka. In the early 1980s, he set up a polybag production unit in Bengaluru, in partnership with his brother, Rasool Khan. Starting with the polybags used in nurseries, the Khan brothers had made KK Plastics a well- known name in the industry by the early 1990s.

In 1995, however, the first set of legislations against the use of plastic came into effect, which was a blow to their business. Retailers started replacing plastic bags with those made from paper. Sales at KK Plastics dipped for the first time in years.

“Municipal corporations around the country have found it extremely difficult to handle plastic waste which threatens soil fertility, the life of stray animals and free flow of sewage through ill-maintained municipality pipelines. Banning plastic polybags seems to be a plausible solution, but unfortunately, it inevitably gets replaced by paper, which isn’t ecologically viable either,” says Ahmed.

He describes the problems of using paper bags. “Apart from causing large-scale deforestation, making paper pulp consumes as much as 20 liters of water for every kilogram of pulp produced. Moreover, the dioxins produced during the bleaching process have the potential to cause immunological, neurological and developmental ailments. Yet, paper bags fail to match the high strength and light weight of their plastic counterparts; neither do they possess any resistance against pests or water. Thus, they have a very short shelf life as compared to plastic polybags and require more frequent recycling. The waste paper releases methane upon rotting, which is a highly potent greenhouse gas.”

Ahmed states that banning plastic polybags is not a solution. “Plastic polybags are just the tip of the iceberg. Plastics form a part of almost everything we use on a daily basis – PET bottles, sachets and so on. Thus, it is almost impossible to get rid of them. Using glass bottles for milk instead of plastic bottles, in addition to being more expensive, would be a big hassle. Recycling these bottles uses a lot of water for cleaning, and if they still remain unclean for some reason, they may pose a health hazard. Also, transporting glass bottles requires special arrangements to prevent breakage, which increases the total volume, and thus, the transportation cost and fuel used, ultimately resulting in higher carbon emissions. In short, given the alternatives, banning plastic polybags does not serve the purpose of protecting the environment as well as it is projected to. A more pragmatic approach is to create systems to handle plastic waste in a better manner.

The policy focus should be on implementing ways to segregate plastic waste at the point of origin, so that it can easily be recycled or put to some other constructive use, rather than ending up in landfills along with all other municipal solid waste.”

Ahmed shares what prompted the company to explore plastic waste management. “We realized that being among those who produce plastics, we should own up to the moral responsibility of finding an eco-friendly way of disposing of the plastics. Therefore, we set out on a path to discover meaningful uses for plastic waste.”

Though neither of the brothers had a degree in science, they set up a small laboratory within the factory premises and started experimenting with plastic waste. “At first, we tried to make a construction brick from it. Those efforts did not yield results, and soon, we had to abandon the idea.

“It then struck us that plastics and bitumen, both being derivatives of petroleum, may have complementary properties. So, we started mixing bitumen with molten plastic and studying the results.

There were several failed attempts, as bitumen was not easily miscible with molten plastic. However, we did not give up. We had a strong intuition that bitumen, when mixed with plastic, should have better strength when used for laying roads.”

Their efforts were finally successful, when they mixed molten plastic at 120°C with bitumen and it yielded a consistent mixture. “We did not know the properties of these substances in great detail. We did not follow a systematic approach or use sophisticated equipment. We just tried whatever we thought could work, and luckily, one of them worked. It was all very simple.”

In order to test the strength of the mixture, the company used it to fill potholes on Bengaluru city’s roads, filling almost 1,000 potholes in various parts of the city over the course of a year. “The results were very encouraging. The filled potholes survived the rainy season without any sign of damage.”

The next step was to adopt the technology on a large scale. “We decided to approach L&T to license our technology to them. However, L&T refused to buy it, saying that they were authorized to use only government-approved materials for road construction; thus, we needed an approval from the government for our technology before they could consider buying it.”

“Getting approval from government authorities required getting approvals from the research institutes authorized to test and validate construction material. We approached the Central Road Research Institute, a CSIR institute for road technology, to get our technology evaluated.

Meanwhile, Rasool’s son, Amjad, who was studying Civil Engineering at RV College of Engineering, presented the technology to one of his professors. The professor was very impressed and proposed to conduct further research and refinement. He proposed partnering with Bangalore University’s Highway Engineering Department for this purpose. We agreed to fund the study; IIT Madras was also involved in the project. Their findings added credibility to our claims that the proposed technology results in longer lasting roads.

Despite the results, obtaining approvals proved to be slow, taking almost three years. However, once we had the required approvals, we confidently approached the Chief Minister of Karnataka, Shri SM Krishna, in 1999.

The CM was very supportive. He wanted to implement the technology across the state for road construction, but the bureaucracy vehemently opposed this, because their interests were aligned with the status quo.

They created all sorts of roadblocks, questioning the technology and even the intention. But the CM prevailed. He directed the BBMP, Bengaluru’s municipal corporation, to cooperate with a 30-km pilot project along Raja Rajeshwari Road.

After years of patience and several hiccups, the 30 km stretch was ready in 2002. We waited for a year for the superior strength of the road to be recognized. Despite a heavy monsoon, the road remained as smooth as if it was laid yesterday. The authorities were amazed with the results.

However, the bureaucrats wanted the road to be tested over a few more monsoons, and thus, the clearance was put on hold. Meanwhile, we proceeded with filing the patent for the technology.

Even after three years, the road was as good as new, and the

babus

were finding it increasingly difficult to defer the matter. The technology was finally granted approval for road construction in 2005. Raja Rajeshwari Road is still undamaged, even after 10 years.”

Road construction using the technology took off after that, until the next roadblock. “We constructed 530 km of roads across Bengaluru in the next two years, before being bogged down by an unanticipated problem – lack of enough plastic waste. Even though Bengaluru was generating as much as 100 tons of plastic waste per day, we found it difficult to collect enough to keep the construction going.”

To deal with this, the company formed another arm called KK Plastic Waste Management to manage the plastic waste collection process. “We offered to buy plastic waste from the rag-pickers at 6 per kg, which was much higher than the 40-50 paise per kg they used to get. The word spread among the rag-pickers, and soon, they started bringing in as much as 25 tons of plastic waste per day.

6 per kg, which was much higher than the 40-50 paise per kg they used to get. The word spread among the rag-pickers, and soon, they started bringing in as much as 25 tons of plastic waste per day.

Unfortunately in India, unlike in many western countries, there is no practice of separating recyclable waste (plastics, paper and glass/metal) at the point of origin (that is, people disposing of used paper, plastic and glass/metal in separate bins at their homes and offices). Thus, the rag-pickers are forced to collect it, which is unhygienic and inhuman, and still, they get a very poor price for their labor.”

KK Plastic Waste Management initiated a plastic collection drive at schools in Bengaluru. They educated children about the harmful effects of plastic waste on the environment and asked them to pass on the message to their parents. Children were encouraged to ask their parents to put the plastic waste in separate bins. The plastic waste collected at home could be brought to the waste plastic collection center at the school and the school was paid 6 per kg for the waste collected, which could be used toward buying library books and computers.

6 per kg for the waste collected, which could be used toward buying library books and computers.

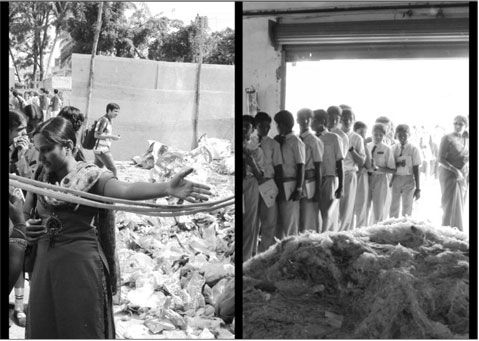

School children being shown the plastic waste collection, segregation, cleaning and grinding process

Collection centers were also set up in several housing societies, in cooperation with the respective Resident Welfare Associations.

“People used to pay to get the waste collected from their homes, and now, they were getting paid for it. The price of 6 per kg served as a good stimulus for people to start handling their plastic waste themselves.”

6 per kg served as a good stimulus for people to start handling their plastic waste themselves.”

The collected plastic waste is segregated into different grades, cleaned, made into a fine powder and then taken to the construction site. At the site, the powder is mixed into bitumen in a proprietary ratio at the aforesaid temperature in hot rollers. The patented mixture, called KK Polyblend, is then used to lay roads. Currently, the company charges the municipal corporation 27 for every kilogram of KK Polyblend used.

27 for every kilogram of KK Polyblend used.