Indian Innovators (5 page)

Developing 3Nethra has been challenging on many technical fronts. Since the medical devices industry is highly research oriented and expects huge profitability, even the most basic functionality in existing devices has been patented.

“We were trying to combine several optical devices into one. For this, we needed to split the light beam so that the same beam can be used for testing multiple things at the same time. Though there are several processes available for this, we had to struggle hard to find a unique way of doing it, so that none of the existing patents were infringed. Moreover, we had to do it in a cost-effective manner that allowed the device to remain portable. This was, by far, the most challenging part of designing 3Nethra.”

The company, fortunately, received early angel funding and did not have to face many financial challenges; most of their challenges were on the technical side. The process involved a high level of R&D inputs and getting the right people was important. “We built a team of around 12 very competent researchers. Most of them had worked with me at either Ericsson or Philips and were passionate about what we were trying to do. We also tied up with IIT Kharagpur and IISc. We have recently managed to obtain a $5 million funding from Accel Partners and IDG Ventures India, two of the leading venture capital funds in the country.”

The company has applied for seven patents on 3Nethra, the most important being the one on cornea imaging, retina imaging and refraction measurement via a single optic line. Besides that, there are patents on image processing and pattern recognition and on indirect measurement of physical parameters.

3Nethra has received due recognition, with the team winning several awards. In 2010, 3Nethra was awarded the Sankalp Award. The Department of Science and Technology (DST) conferred the Lockheed Martin Gold Medal upon it in 2011. The same year, it also received the Piramal Award, the Samsung Innovation Quotient Award and the Anjali Mashelkar Inclusive Innovation Award.

Shyam shares his future plans. “We are now working on another device, ROP (Retinopathy of Prematurity) machine.” ROP affects prematurely born babies. The eye is the last organ to develop in the fetus, and sometimes, when a baby is born prematurely, the retina is not yet fully developed. In many such cases, the retina can grow unusually fast over the 3-6 weeks after birth. The disorganized growth of retinal blood vessels may result in scarring and retinal detachment, which, if not treated in time, can lead to blindness.

“We need to scan about 3-4 million prematurely born babies each year for ROP. You need a special, wide angle camera to do this. Only a couple of companies currently produce such cameras and they easily cost several crores each. There are just 30-40 such cameras available in India. The ROP detection device we are developing would be substantially cheaper and much easier to use than any other available right now. Since most of the premature births occur in hospitals, many hospitals have shown interest in the device.

The 3Nethra pediatric machine, designed for children in the age group of 3-8 years, is also in the pipeline. This is the age group during which the imaging system of the eye develops. Many eye ailments, like squint, develop during this age, but become observable only at a much later stage, when it is usually too late. It is easily treatable in the initial stages. Thus, this device would help in the timely detection of eye ailments peculiar to this age group.”

An innovator once is an innovator for a lifetime. Shyam is a visionary with an inspiring passion for innovation and social good. We hope his work goes on to serve the masses across the globe.

For the Innovator in You

“The progress in 3Cs – communication, computation and collaboration – has made it much easier for people to acquire and share knowledge. With the emergence of new and fairer business models, there is renewed vigor around the world to innovate for the people at the bottom of the pyramid. It is an underserved market that innovators should focus on, to earn good financial returns as well as great satisfaction.

In India, companies in the service industry multiply their wealth very fast, but this does not happen for a product-based company. Market acceptance for a product may take time, so one should be patient. Also, financial resources must be managed such that you do not have to be in a rush to make money.”

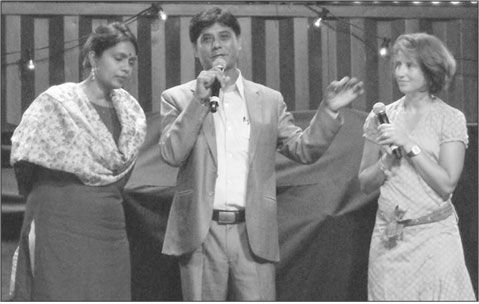

Mansukhbhai recounting his MittiCool story to foreign audience via an interpreter

MittiCool Refrigerator

Mansukhbhai Prajapati may be the most popular Indian innovator that you have never heard of. He is the poster boy of grassroots level innovators in India, and has been featured in almost every newspaper in India, in the

Harvard Business Review

and even on Discovery Channel and BBC.

Mansukhbhai comes from a traditional clay potters’ family. He was born in Nichimandal village, in Morbi district of Gujarat’s Saurashtra region. Morbi is known for its glazed ceramic tiles and has several kilns.

In 1979, Nichimandal was destroyed by floods and Mansukhbhai’s father was forced to migrate to Rajkot, where he found work as a construction laborer for daily wages. Mansukhbhai was left behind with his grandparents in Wakaner, 70 km from Morbi.

At the age of seven, his marriage was fixed with a girl from a relatively well-off family. He continued to study, but failed his class X exams. His father then arranged for him to work in a brick kiln, but Mansukhbhai hated it because of the dust. Soon, he convinced his father to let him buy a pushcart to sell tea on the highway, just outside Wakaner, but the endeavor didn’t last too long.

“I enjoyed being a tea-vendor, but I lived in the fear that my in-laws would see me and call off the marriage. I used to hide behind my push-cart whenever my in-laws passed by the highway. Though the business was doing fine, I didn’t want to lose my bride-to-be for it.”

One day, the owner of a factory that made red roof tiles came to his stall. As he was having tea, he asked Mansukhbhai if he knew any young boy of his age who may be looking for employment. Sixteen-year-old Mansukh almost screamed in excitement that he was available. Even before the factory owner could tell him what the job entailed or how much he would be paid, he had accepted it.

The job at the factory required staying 24×7 within the factory premises. Day-to-day activities involved looking after the security and counting the roof tiles before they were loaded on the truck. Sometimes, Mansukhbhai had to substitute for any laborer who would call in sick.

“I was paid 10 a day, along with meals and had the factory floor for a bed. For the next six years, I did every odd job at the factory, from repairing the machinery to making the clay and sweeping the floor.”

10 a day, along with meals and had the factory floor for a bed. For the next six years, I did every odd job at the factory, from repairing the machinery to making the clay and sweeping the floor.”

In 1988, at the age of 22, he married the woman he was betrothed to. Later that year, he left the job at the factory and started a workshop for making motor windings, in partnership with a friend who knew a little about making motors.

“As it turned out, he knew very little. The first batch of motors burned up on their very first use at the factory that had ordered them.” The business incurred heavy losses and had to be shut down after six months.

Mansukhbhai then started a shop to sell sweets and snacks

(bhajiya).

This venture too ended unsuccessfully within six months, leaving Mansukhbhai in deep financial trouble. He was forced to approach moneylenders.

“I asked a few

lalajis

for a loan of 50,000. Because I did not have anything to offer as security, they weren’t so keen to lend, despite the high interest rate that they usually charged.”

50,000. Because I did not have anything to offer as security, they weren’t so keen to lend, despite the high interest rate that they usually charged.”

Somehow, the owner of the roof-tile factory came to know of his plight through one of the moneylenders Mansukhbhai had approached. “He told the

lalaji

about my honesty and even agreed to provide the backing for the loan in case of default. He personally came to my house along with

lalaji

to give me the much-needed 50,000. However, I was away from home at that time, and my father, unaware of my financial situation, told them that we did not need to borrow money.

50,000. However, I was away from home at that time, and my father, unaware of my financial situation, told them that we did not need to borrow money.

Later,

lalaji

agreed to lend me 30,000 at 18% interest, which I accepted.”

30,000 at 18% interest, which I accepted.”

With the money left after repaying earlier debts, Mansukhbhai purchased some land and decided to enter the family’s traditional business of clay pottery. His father, however, was against the idea, because he knew that there was little money to make in this profession. Mansukhbhai stood firm, for he felt that “it was at least a stable business and required less capital to start.”

He started making clay flat pans

(tawas),

but due to his inexperience, broke about 25,000

tawas

in the first year and ended up with zero profit. However, things gradually started to change for the better.

By 1990, the family together made about 100

tawas

a day, but the money they earned was barely enough for survival. Mansukhbhai wanted to scale up the business, but could not afford to hire additional labor. Therefore, he thought about making a machine to make

tawas.

For about a year, he experimented with several dies and finally succeeded in making a press for manufacturing clay

tawas

. This was his first in a series of innovations. The production increased from 100 to 1,000

tawas

a day. Where Mansukhbhai would earlier sell

tawas

going from one village to another on bicycle, he now hired an auto-rickshaw.

In 1992, Mansukhbhai introduced a new offering, a clay pot

(matka)

with beautiful colors and designs.

“People found the shape and designs of the

matka

so attractive that we would sell whatever we produced almost as soon as we reached the market.”

Mansukhbhai’s financial woes were now over, but he wanted to do something more than just making a living.

On observing that the pond water that the villagers drank was quite polluted and often led to sickness, he started thinking about making a pot that could provide purified water.

By 1995, completely on his own, he had made a clay filter with pores as fine as 0.9 microns. He put the filter between two clay pots to create a system that provided clean and cool water at a nominal price of 100.

100.

The earthquake that rocked Gujarat in January 2001 also jolted Mansukhbhai’s hitherto comfortable life. The earthquake, measuring 7.7 on the Richter scale, is estimated to have left 20,000 people dead and another 160,000 injured. About 400,000 homes were destroyed and 600,000 people were left homeless, with the economic loss billed at about $5.5 billion.

Since it was winter, Mansukhbhai had stocked 5,000

matkas

for sale during summer. Where brick-and-cement houses could not withstand the earth’s fury, the clay pots too were shattered within seconds.

A reporter passing through Wakaner saw the pile of shattered

matkas

and clicked a few pictures. On February 26, 2011, exactly a month after the earthquake, a leading Gujarati daily,

Sandesh

carried the pictures on the first page with a caption that translates to “Poor man’s refrigerator shattered”.

This set Mansukhbhai thinking about making an actual refrigerator for the poor.

“Matka hi garibon ka fridge hota hai. Gareeb logon ke paas fridge khareedne ke paise nahin hote, na hi usse chalane ke liye bijli ka bill dene ki kshamata. To maine socha ki kyun na mitti se aisa fridge banaun jo sasta ho aur bijli ke bina chale

.” (The clay pot is a refrigerator for

the poor. They do not have the money to buy a refrigerator; nor can they afford to pay electricity bills. So, I thought, why not make a clay refrigerator that is cost-effective and works without using electricity.)

He decided to use the principles employed daily by vegetable vendors in India. During the summer, these vendors cover their vegetables with a wet cloth and keep sprinkling water over it. Evaporation maintains a cooler and stable temperature beneath the cloth and keeps the vegetables fresh.

Meanwhile, a newspaper reporter wrote about Mansukhbhai’s effort to make the clay refrigerator. The news spread like wildfire, and soon, various newspapers were talking about this unimaginable endeavor. People started visiting Mansukhbhai and enquiring about the progress, though in reality, little had been achieved. However, this increased Mansukhbhai’s resolve to realize his dream project. There were several failed attempts, each costing a lot of money.

“After the earthquake, the Gujarat government started giving loans to people to start new businesses, so that more people would get employment, which would help to restore normalcy in Gujarat. I applied for a loan of 7 lakh and it was approved. I put all the money toward making the refrigerator, but it still did not reach the required level of cooling. In order to pay the interest on the loan, I had to sell my house. I then sold my push-cart and a few other possessions as well. People started calling me mad.

7 lakh and it was approved. I put all the money toward making the refrigerator, but it still did not reach the required level of cooling. In order to pay the interest on the loan, I had to sell my house. I then sold my push-cart and a few other possessions as well. People started calling me mad.