India (Frommer's, 4th Edition) (278 page)

Note:

At press time, tax on Rajasthan hotel accommodations varied between 8% and 10% (depending on the city), although this does not apply to economy rooms; sales tax of 12.5% is charged on dining bills.

An Aravalli Ramble

If you wish to try a largely city-free option that will encourage a more peaceful, activity based trip, far from the crowds and tourist groups then try the rustic beauty and pastoral tranquillity of the ancient Aravalli Hills and its folk and culture. It is possible to plan your itinerary accordingly and overnight at properties that are not diluted by the chaos, pressures, and noise of larger cities. Even the smaller towns, while charming, can sometimes break the hypnotic calm of an Aravalli countryside sojourn. You can choose a route with the appropriate properties, together with unique activities, that maintains the distinct charm of these villages and its people. A recommended route (southwest to northeast, Udaipur to Delhi, or vice versa), which tracks the Aravalli Range, would include the lakeside Deco heritage of Dungapur’s Udai Bilas Palace. Then move on to Udaipur, where you can escape the crowds by staying a night at Devi Garh before moving on to the charming Rawla Narlai. Then you could take in the impressive Kumbhalgarh Fort and the Jain temples at Ranakpur (overnighting at HRH’s Aodi). After that head northeast towards Bhilwara and the homely Shahpura Bagh (halfway between Udiapur and Jaipur) for a few days before the drive to Jaipur. After shopping and sightseeing in the Pink City spend a night at Samode Palace after seeing the Amber Fort, but be sure not to miss Amanbagh for a final few days of relaxation and pampering before the short trek to Delhi and home.

WHERE TO STAY & DINE EN ROUTE TO OR FROM DELHI

Instead of hightailing it to or from the capital, consider breaking up your journey and enjoying some of the marvelous luxury and architectural heritage available between Delhi and Jaipur.

Amanbagh For its inspired location alone, this fabulous Amanresort property deserves three stars. Made almost entirely of pink sandstone by local stonemasons, the best and most expensive suites are the palatial pool pavilions. A light-filled entrance foyer leads directly through to your own emerald marble pool, a gorgeous, massive bedroom on one side and a spacious domed bath chamber on the other. For significantly fewer dollars, you can forgo a private pool (arguably eclipsed by the 33m/108 ft. marbled magnetic main pool), while still being thoroughly ensconced in luxury in one of the three categories of haveli suite (the elevated terrace units are best, up in the mango trees gazing directly at the hills; ask for one facing the canal rather than the pool). If you can bear to leave the premises, you can undertake a number of truly worthwhile activities: picnics into the countryside, hike to ancient Somsagar Lake, explore the haunted ruins at Bhangarh, visit the archaeological sites in the Paranagar area. Amanbagh’s staff is enchanting: warm, discreet; dining is world-class.

For its inspired location alone, this fabulous Amanresort property deserves three stars. Made almost entirely of pink sandstone by local stonemasons, the best and most expensive suites are the palatial pool pavilions. A light-filled entrance foyer leads directly through to your own emerald marble pool, a gorgeous, massive bedroom on one side and a spacious domed bath chamber on the other. For significantly fewer dollars, you can forgo a private pool (arguably eclipsed by the 33m/108 ft. marbled magnetic main pool), while still being thoroughly ensconced in luxury in one of the three categories of haveli suite (the elevated terrace units are best, up in the mango trees gazing directly at the hills; ask for one facing the canal rather than the pool). If you can bear to leave the premises, you can undertake a number of truly worthwhile activities: picnics into the countryside, hike to ancient Somsagar Lake, explore the haunted ruins at Bhangarh, visit the archaeological sites in the Paranagar area. Amanbagh’s staff is enchanting: warm, discreet; dining is world-class.

Ajabgarh, Rajasthan. 01465/22-3333.

01465/22-3333.

Fax 01465/22-3335.

www.amanresorts.com

. [email protected]. Reservations: Amanresorts Corporate Office 77/774-3500

77/774-3500

in Colombo 24/7. Fax 011/237-2193. [email protected]. 40 Units. $1,250 pool pavilion; $850 terrace haveli; $700 garden haveli; $650 courtyard haveli. Rates exclude 10% service charge. AE, MC, V.

Amenities:

2 restaurants; bar; doctor-on-call; gym; Internet (complimentary); library; guided meditations; 2 heated pools; room service; safaris—horse, camel, jeep; spa; walks; yoga. In room: A/C, CD player, minibar, pool pavilion rooms have private heated pool; Wi-Fi (complimentary).

Once Were Warriors: The History of the Rajput

Rajasthan’s history is inextricably entwined with that of its self-proclaimed aristocracy: a warrior clan, calling themselves Rajputs, that emerged sometime during the 6th and 7th centuries. Given that no one too low in the social hierarchy could take the profession (like bearing arms) of a higher caste, this new clan, comprising both indigenous people and foreign invaders such as the Huns, held a special “rebirth” ceremony—purifying themselves with fire—at Mount Abu, where they assigned themselves a mythical descent from the sun and the moon. In calling themselves Rajputs (a corruption of the word Raj Putra, “sons of princes”), they officially segregated themselves from the rest of society. Proud and bloodthirsty, yet with a strict code of honor, they were to dominate the history of the region right up until independence, and are still treated with deference by their mostly loyal subjects.

The Rajputs offered their subjects protection in return for revenue, and together formed a kind of loose kinship in which each leader was entitled to unequal shares within the territory of his clan. The term they used for this collective sharing of power was “brotherhood,” but predictably the clan did not remain a homogenous unit, and bitter internecine wars were fought. Besides these ongoing internal battles, the Hindu Rajputs had to defend their territory from repeated invasions by the Mughals and Marathas, but given the Rajputs’ ferocity and unconquerable spirit, the most skillful invasion came in the form of diplomacy, when the great Mughal emperor Akbar married Jodhabai, daughter of Raja Bihar Mal, ruler of the Kachchwaha Rajputs (Jaipur region), who then bore him his first son, Jahangir.

Jahangir was to become the next Mughal emperor, and the bond between Mughal and Rajput was cemented when he in turn married another Kachchwaha princess (his mother’s niece). A period of tremendous prosperity for the Kachchwaha clan followed, as their military prowess helped the Mughals conquer large swaths of India in return for booty. But many of the Rajput clans—particularly those of Mewar (in the Udaipur region)—were dismayed by what they saw as a capitulation to Mughal imperialism. In the end it was English diplomacy that truly tamed the maharajas. Rather than waste money and men going to war with the Rajput kings, the English offered them a treaty. This gave “the Britishers” control of Rajputana, but in return the empire recognized the royal status of the Rajputs and allowed them to keep most of the taxes extorted from their subjects and the many travelers who still plied the trade routes in the Thar Desert.

This resulted in a period of unprecedented decadence for the Rajputs, who now spent their days hunting for tigers, playing polo, and flying to Europe to stock up on the latest Cartier jewels and Belgian crystal. Legends abound of their spectacular hedonism, but perhaps the most famous surround the Maharaja Jai Singh of Alwar (north of Jaipur), who wore black silk gloves when he shook hands with the English king and reputedly used elderly women and children as tiger bait. When Jai Singh visited the showrooms of Rolls-Royce in London, he was affronted when the salesman implied that he couldn’t afford to purchase one of the sleek new models—he promptly purchased 10, shipped them home, tore their roofs off, and used them to collect garbage. The English tolerated his bizarre behavior until, after being thrown from his horse during a polo match, he doused the animal with fuel and set it alight. Having ignored previous reports of child molestation, the horse-loving British finally acted with outrage and exiled him from the state.

Above all, the Rajput maharajas expressed their newfound wealth and decadence by embarking on a frenzied building spree, spending vast fortunes on gilding and furnishing new palaces and forts. The building period reached its peak in Jodhpur, with the completion of the Umaid Bhawan Palace in the 1930s, at the time the largest private residence in the world.

When the imperialists were finally forced to withdraw, the “special relationship” that existed between the Rajputs and the British was honored for another 3 decades—they were allowed to keep their titles and enjoyed a large government-funded “pension,” but their loyalty to the British, even during the bloody 1857 uprisings, was to cost them in the long run.

In 1972 Prime Minister Indira Gandhi—sensibly, but no doubt in a bid to win popular votes—stripped the Rajputs of both stipends and titles. This left the former aristocracy almost destitute, unable to maintain either their lifestyles or their sprawling properties. While many sold their properties and retired to middle-class comfort in Delhi or Mumbai, others started opening their doors to paying guests like Jackie Kennedy and members of the English aristocracy, who came to recapture the romance of Raj-era India. By the dawn of a new millennium, these once-proud warriors had become first-rate hoteliers, offering people from all walks of life the opportunity to experience the princely lifestyle of Rajasthan.

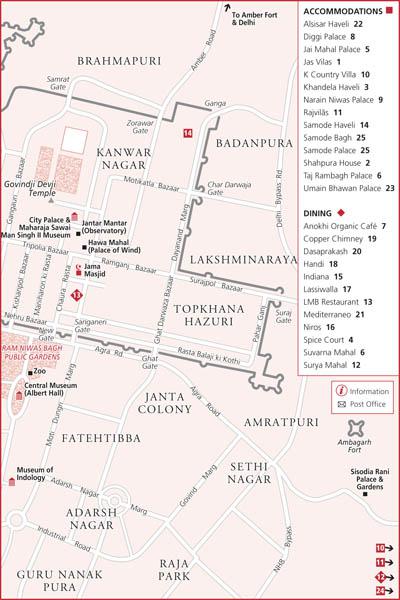

2 Jaipur

262km (162 miles) SW of Delhi; 232km (144 miles) W of Agra

Jaipur