In Patagonia (21 page)

Authors: Bruce Chatwin

But the Onas did have one swift and daring marksman called Täapelt, who specialized in picking off white murderers with cold selective justice. Täapelt stalked the Red Pig and found him out man-hunting one day with the local Chief of Police. One arrow pierced the policeman's neck. The other sank into the Scotsman's shoulder, but he recovered and had the arrow head mounted as a tie-pin.

The Red Pig found his nemesis in the liquor of his own country. Drunk by day and night, the Menéndez family sacked him. He and his wife Bertha retired to a bungalow in Punta Arenas. He died of delirium tremens in his mid-forties.

57

âB

UT THE Indians

did

get the Red Pig, you know.' The speaker was one of two English spinster ladies I met later in Chile. Both were in their seventies. Their father had been manager of a meat-works in Patagonia and they were on holiday in the South looking up old friends. They lived in a flat in Santiago. They were nice ladies and they spoke with nice ladylike accents.

UT THE Indians

did

get the Red Pig, you know.' The speaker was one of two English spinster ladies I met later in Chile. Both were in their seventies. Their father had been manager of a meat-works in Patagonia and they were on holiday in the South looking up old friends. They lived in a flat in Santiago. They were nice ladies and they spoke with nice ladylike accents.

Both wore a lot of make-up. They had plucked their eyebrows and painted them in higher up. The elder sister was blonde, bright gold to be exact, and white at the roots. Her lips were a scarlet bow and her eyelids were green. The younger one was brunette. Her hair, eyebrows, suit, handbag, and spotted silk cravat were a matching shade of chocolate; even her lips were a kind of reddish brown.

They were taking tea with a friend and the sun came in off the sea, filling the room and shining on their lined and painted faces.

âOh, we knew the Red Pig well,' the blonde one said, âwhen we were gels in Punta Arenas. He and Bertha lived in a funny little house round the corner. The end was terrible. Terrible! Kept seeing Indians in his sleep. Bows and arrows, you know. And screaming for blood! One night he woke and the Indians were all round the bed and he cried: “Don't kill me Don't kill me!” and he ran out of the house. Well, Bertha followed down the street but she couldn't keep up, and he ran right on into the forest. They lost him for days. And then a peon found him in a pasture with some cows. Naked! On all fours And eating grass! And he was bellowing like a bull because he thought he

was

a bull. And that was the

end

of course.'

was

a bull. And that was the

end

of course.'

58

T

HE GERMAN Esteban gave me a spare cot for the night and then we saw the headlights of a car. It was a taxi, taking a peon to the estancia I was aiming for. They left me at the front gate.

HE GERMAN Esteban gave me a spare cot for the night and then we saw the headlights of a car. It was a taxi, taking a peon to the estancia I was aiming for. They left me at the front gate.

âWell, at least the visitor speaks English.'

The voice came round the door of a sitting-room where a log fire was blazing.

Miss Nita Starling was a small, agile Englishwoman, with short white hair, narrow wrists and an extremely determined expression. The owners of the estancia had invited her to help with the garden. Now they did not want her to go. Working in all weathers, she had made new borders and a rockery. She had unchoked the strawberries and under her care a weed-patch had become a lawn.

âI always wanted to garden in Tierra del Fuego,' she said next morning, the light rain washing down her cheeks, âand now I can say I've done it.'

As a young woman Miss Starling was a photographer, but learned to despise the camera. âSuch a kill-joy,' she said. She then worked as a horticulturalist in a well-known nursery garden in Southern England. Her special interest was in flowering shrubs. Flowering shrubs were her escape from a rather drab life, looking after her bed-ridden mother, and she began to lose herself in their lives. She pitied them, planted out unnaturally in nursery beds, or potted up under glass. She liked to think of them growing wild, on mountains and in forests, and in her imagination she travelled to the places on the labels.

When Miss Starling's mother died, she sold the bungalow and its contents. She bought a lightweight suitcase and gave away the clothes she would never wear. She packed the suitcase and walked it round the neighbourhood, trying it out for lightness. Miss Starling did not believe in porters. She did pack one long dress for evening wear.

âYou never know where you'll end up,' she said.

For seven years she had travelled and hoped to travel till she dropped. The flowering shrubs were now her companions. She knew when and where they would be coming into flower. She never flew in aeroplanes, and paid her way teaching English or with the odd gardening job.

She had seen the South African veld aflame with flowers; and the lilies and madrone forests of Oregon; the pine woods of British Columbia; and the miraculous unhybridized flora of Western Australia, cut off by desert and sea. The Australians had such funny names for their plants: Kangaroo Paw, Dinosaur Plant, Gerardtown Wax Plant and Billy Black Boy.

She had seen the cherries and Zen gardens of Kyoto and the autumn colour in Hokkaido. She loved Japan and the Japanese. She stayed in youth hostels that were lovely and clean. In one hostel she had a boyfriend young enough to be her son. She gave him extra English lessons, and, besides, the young liked older people in Japan.

In Hong Kong Miss Starling had boarded with a woman called Mrs Wood.

âA dreadful woman,' Miss Starling said. âTried to pretend she was English.'

Mrs Wood had an old Chinese servant called Ah-hing. Ah-hing was under the impression that she was working for an Englishwoman, but could not understand why, if she were English, she would treat her that way.

âBut I told her the truth,' Miss Starling said. â“Ah-hing,” I said, “your employer is not English at all. She's a Russian Jewess.” And Ah-hing was upset because all the bad treatment was now explained.'

Miss Starling had an adventure staying with Mrs Wood. One night she was fumbling for her latchkey when a China-boy put a knife to her throat and asked for her handbag.

âAnd you gave it him,' I said.

âI did no such thing. I bit his arm. I could tell he was more frightened than me. Not what you'd call a professional mugger, see. But there's one thing I'll always regret. I so nearly got his knife off him. I'd have loved it for a souvenir.'

Miss Starling was on her way to the azaleas in Nepal ânot this May but the one after'. She was looking forward to her first North American Fall. She quite liked Tierra del Fuego. She had walked in forests of

notofagus antarctica.

They used to sell it in the nursery.

notofagus antarctica.

They used to sell it in the nursery.

âIt is beautiful,' she said, looking from the farm at the black line where the grass ended and the trees began. âBut I wouldn't want to come back.'

âNeither would I,' I said.

59

I

WENT on to the southernmost town in the world. Ushuaia began with a prefabricated mission house put up in 1869 by the Rev. W. H. Stirling alongside the shacks of the Yaghan Indians. For sixteen years Anglicanism, vegetable gardens and the Indians flourished. Then the Argentine Navy came and the Indians died of measles and pneumonia.

WENT on to the southernmost town in the world. Ushuaia began with a prefabricated mission house put up in 1869 by the Rev. W. H. Stirling alongside the shacks of the Yaghan Indians. For sixteen years Anglicanism, vegetable gardens and the Indians flourished. Then the Argentine Navy came and the Indians died of measles and pneumonia.

The settlement graduated from navy base to convict station. The Inspector of Prisons designed a masterpiece of cut stone and concrete more secure than the jails of Siberia. Its blank grey walls, pierced by the narrowest slits, lie to the east of the town. It is now used as a barracks.

Mornings in Ushuaia began in flat calm. Across the Beagle Channel you saw the jagged outline of Hoste Island opposite and the Murray Narrows, leading down to the Horn archipelago. By mid-day the water was boiling and slavering and the far shore blocked by a wall of vapour.

The blue-faced inhabitants of this apparently childless town glared at strangers unkindly. The men worked in a crab-cannery or in the navy yards, kept busy by a niggling cold war with Chile. The last house before the barracks was the brothel. Skull-white cabbages grew in the garden. A woman with a rouged face was emptying her rubbish as I passed. She wore a black Chinese shawl embroidered with aniline pink peonies. She said â

¿Qué tal?'

and smiled the only honest, cheerful smile I saw in Ushuaia. Obviously her situation suited her.

¿Qué tal?'

and smiled the only honest, cheerful smile I saw in Ushuaia. Obviously her situation suited her.

The guard refused me admission to the barracks. I wanted to see the old prison yard. I had read about Ushuaia's most celebrated convict.

60

T

HE STORY of the Anarchists is the tail end of the same old quarrel : of Abel, the wanderer, with Cain, the hoarder of property. Secretly, I suspect Abel of taunting Cain with âDeath to the Bourgeoisie!' It is fitting that the subject of this story was a Jew.

HE STORY of the Anarchists is the tail end of the same old quarrel : of Abel, the wanderer, with Cain, the hoarder of property. Secretly, I suspect Abel of taunting Cain with âDeath to the Bourgeoisie!' It is fitting that the subject of this story was a Jew.

May Day of 1909 was cold and sunny in Buenos Aires. In the early afternoon, files of men in flat caps began filling the Plaza Lorea. Soon the square pulsed with scarlet flags and rang with shouts.

Swirling along with the crowd was Simón Radowitzky, a redhaired boy from Kiev. He was small but brawny from working in railway yards. He had the beginnings of a moustache and his ears were big. Over his skin hung the pallor of the ghettoââunpleasantly white', the police dossier said. A square jutting chin and low forehead spoke of limited intelligence and boundless convictions.

The cobbles underfoot, the breath of the crowd, the stuccoed buildings and sidewalk trees; the guns, horses and police helmets, carried Radowitzky back to his city and the Revolution of 1905. Gravelly voices mixed with Italian and Spanish. The cry went up âDeath to the Cossacks!' And the rioters, loosing control, smashed shop-windows and unhitched horses from their cabs.

Simón Radowitzky had been in a Tsarist jail. He had been in Argentina three months. He lived with other Russian Jewish Anarchists in a tenement. He drank in their hot talk and planned selective action.

Across the Avenida de Mayo, a cordon of cavalry and a single automobile checked the advance of the crowd. In the car was the Chief of Police, Colonel Ramón Falcón, eagle-eyed, impassive. The front-rankers spotted their enemy and shouted obscenities. Calmly, he calculated their numbers and withdrew.

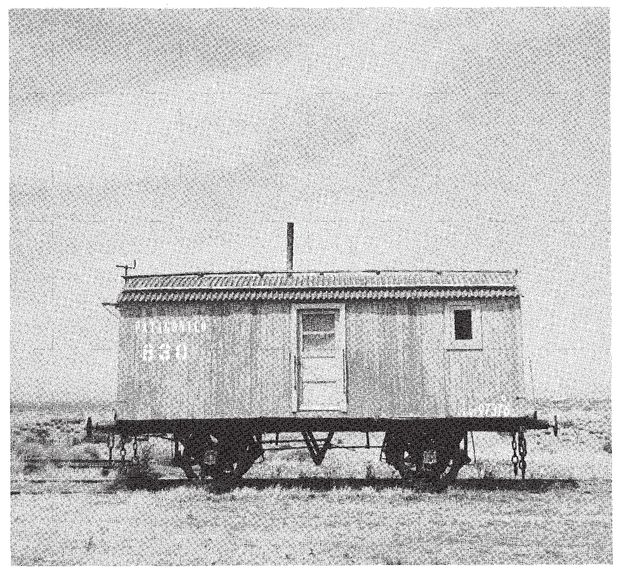

Patagonian Railways

Jaramillo Station

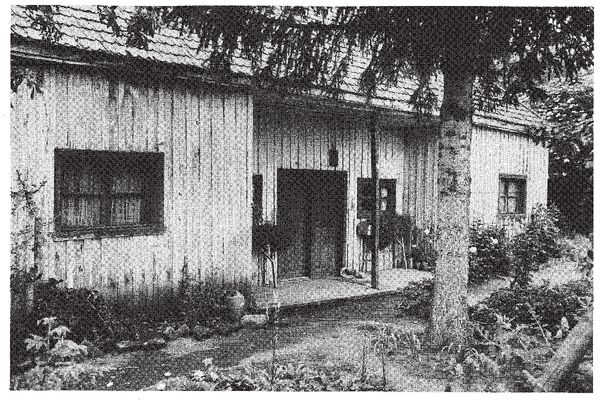

The Tomb at Rio Pico

Other books

The Woman He Loved Before by Koomson, Dorothy

Twelfth Krampus Night by Matt Manochio

Lord of the Isle by Elizabeth Mayne

Supernatural: Carved in Flesh by Waggoner, Tim

Party Princess by Meg Cabot

Swindled in Paradise by Deborah Brown

The House That Jack Built by Graham Masterton

Jason Frost - Warlord 04 - Prisonland by Jason Frost - Warlord 04

The Carpenter's Children by Maggie Bennett

The Ruby Talisman by Belinda Murrell