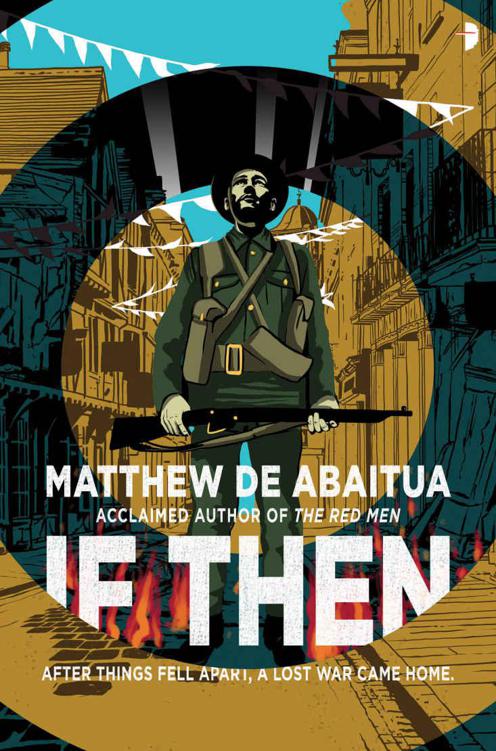

If Then

Authors: Matthew de Abaitua

If Then

Matthew de Abaitua

For my children

T

he front cannot

but attract us, because it is, in one way, the extreme boundary between what one is already aware of, and what is still in the process of formation.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin,

The Makings of a Mind

T

oday’s truths

become errors tomorrow; there is no final number.

Yevgeny Zamyatin,

On Literature, Revolution, Entropy, and Other Matters

IF

1

W

hatever he was

, he was not quite a man. The bailiff found the soldier hanging off a coiled bank of barbed wire running through the heart of Blackcap farmhouse. The soldier did not seem to feel pain and struggled in silence to free his arms and chest from the metal thorns. Though his features were well-defined – a blade of a nose and dark brows – the eyes were mindless, the mouth loose and undirected. No, not quite a man.

The soldier bucked urgently against the new, coarse-cut wire, opening up a bloodless wound: his skin parted along a seam on his forearm, revealing pulpy flesh threaded with spokes of tightly-packed crimson seeds like a pomegranate. The bailiff grasped the hard pale sheen of the soldier’s wrist, just above the wound. The soldier’s uniform – overcoat and pack, a light khaki tunic with two breast-pockets, woollen trousers with a safety pin through the waistband, puttees and hob-nailed boots – smelt of damp earth and the chemical cleansers of the assembly line. He wore an armlet marked with two red letters:

SB

.

The bailiff knelt down and stroked the soldier’s close-cropped hair as if calming a child crying in the night.

“My name is James,” said the bailiff.

Then James pressed his right boot against the wire and gently lifted the struggling soldier off its spikes. Once free, the soldier turned slowly on his back, readjusting, realigning. James clambered over the wire and onto the soldier’s chest, reached into the tunic and found a pair of bandages, then set about binding the wound. There was neither a flicker of thanks nor relief upon the face of the soldier, his eyes merely agitating at the speeding clouds overhead.

James tucked the bandage back into the soldier’s pocket, then noted, tied around his neck, a pair of identity discs: a brick-coloured circle and green hexagon threaded with knotted string and imprinted with the name of

J Hector

. In Hector’s backpack there was a blank sketchbook, a tin of watercolour paints, a coarse blanket, shining tins of iron rations, a primus stove and a water bottle. The water bottle was full and James offered it to Hector. His lips inclined toward it. He drank. Water was necessary, it seemed. James hauled Hector to his feet. His clothes were sodden with dew, a sign that he had been on the wire since before dawn.

A sea fret drifted over the downland. James pointed to where the bowl of lush green curved upward to the ridgeline. He began his ascent and motioned for Hector to follow. The soldier did not respond.

“Who made you?” asked James.

Hector’s chest rose and fell. He breathed like a man. He drank like a man. He looked like a man. But inside he was pith and beads.

“Did the Process make you?”

No answer. James looked back across the quiet valley. He had seen some things on his patrols of the Downs, but this was new. At least he thought it was. His memory was full of holes.

It was six miles back to town but only four miles across to Glynde. From there he could take a route through the woodland to the Institute. Alex Drown would be interested in the soldier. He would take him to her.

He tried pushing Hector forward. The soldier stumbled on for a few steps then stopped and half-turned back toward James. The will of the Process could ignite within the soldier at any moment: he should drive Hector forward now before resistance rose within him. But James was loathe to show such violence, even to a manufactured man. He believed in kindly discipline, the fatherly appeal to reason, although he had no children himself. He and Ruth had not been so blessed.

James returned to the ruined barn, found a rope, and tied it around Hector’s midriff to use as a leash. He climbed toward the escarpment, yanking at Hector to follow him. The soldier stumbled and fell forward without bringing up his arms to protect himself. James would have to carry him. A fireman’s lift. James was tall and broad, sixteen stone of muscle and one stone of fat. With the soldier slumped uncomplaining across his shoulders, James staggered to the top of the chalk ridge.

Radio masts lay fallen across the western track, broken into thirds and rusting into the earth. He lay Hector down and went inside the relay station to check for signs of the evicted. The previous week he had evicted three people from the town and sometimes they did not get very far. The relay station was empty.

His patrol route followed the ridge down to the river, then along its course north into town. Hector had been caught up in the south side of the wire, and so must have come from the direction of the coast. James shielded his eyes and gazed out to sea: three long tankers laden with scrap and containers idled at anchor, waiting for a berth in the port. The new owners of Newhaven had found a use for their acquisition: the port was busier than when it had been inhabited by people. He had not been to Newhaven since the Seizure. His memories of that night were mercifully vague: faces screaming in the spotlights; his giant iron hand peeling back a roof to find a family huddled in their beds; raindrops quivering on the porthole; the silence afterwards; rusting hulls rocking in the oily waters of the harbour.

James headed down the steep old road toward Firle village. The tarmac was cracked. The scent of a colony of wild garlic, clustered in the dappled sunlight at the foot of an oak, reminded him of past trips to the village, before the Seizure, when paragliders rode the thermals rising up Firle Beacon. The view from the air was different now. Ancient and modern ruins merged into one another: the faded road markings just visible through the hawthorn, the mounds of barrow and iron fort, the rotten thatch of a country pub and the flyblown carriage of a lost commuter train, and then the great old houses with their fortified estates, the reservoir, the woodsmoke rising from the encampments of the foresters, and Lewes itself, his home, protected.

The broken road skirted around the edge of the Firle estate. The cottage doors were painted green to mark their ownership by the viscount and his family. Children played in the gardens and in the street. A girl of about ten years old, with straight blonde hair, followed him as he walked; she cartwheeled first with two hands, then with one.

When he paid her no attention, she called out, “Who’s the man on your back, bailiff?”

She wore a homemade gingham dress and was barefoot. She wore her hair in a ponytail tied with ribbons made by his wife. Many of the women wore their hair that way as it concealed the stripe.

“His name is Hector,” James replied. He lowered the soldier to the ground.

“Is he hurt?”

“Yes.”

“So why doesn’t he cry?”

“Because he’s not quite a man,” said James.

“He looks like a man.”

“He’s not as heavy as a man. Somebody made him.”

“Like a doll?” asked the girl.

“Yes.”

“To play a game with?”

“Perhaps.”

“My dad found one in the river,” she said. “He wasn’t a real man either.”

“When was this?”

“Last week. He was dressed as a soldier man too.”

“A soldier from the olden days?”

“From the First World War,” the girl corrected him, taking pride in her knowledge. “We all had a look at him. He was different from this one. Chunkier.”

“Is your father around?”

“No, bailiff,” she shook her head. All the children lied to him: the angle of her left foot, pointed inward, the adjustment of her hair over her right ear, her scrupulous effort not to glance back through the avenue of overgrown sycamore, were all signs for him to sift.

“Where is your soldier now?”

“They took him to the Institute tied to a wheelbarrow. Is that where you’re taking this one?”

“Tied?”

“The soldier didn’t want to go. This one seems not so alive.”

“The Process is weaker in the valleys. Where are your parents?” He felt responsible for the girl now and didn’t want to leave her out alone.

“Don’t you remember my name?” she asked. “We met at the lido. Your wife is my teacher.”

“I don’t have a very good memory,” he confessed.

She looked concerned.

“Are you sick?”

“I had an operation,” he explained. “It had side effects.”

“You had an operation to make you the bailiff. We learnt about it at school.”

“You know a lot of things.”

“My name is Agnes,” she said.

Hector stirred. The soldier ran one hand along the hobnailed sole of his boot, recalling the sensation of the earth beneath his feet.

“He’s like my cat,” said Agnes. “He’s with us but he’s alone too.”

“He’s part of the Process,” said James.

“Why?”

“I don’t understand the Process. I just follow it. The Institute will know what he is for.”

James bent down and heaved Hector onto his shoulder; the body had grown denser, and palpably heavier with presence. Time was running out. Agnes, idly chewing the ends of her long straight blonde hair, watched the bailiff struggle down the lane, the dappled light through overhanging branches playing upon the face of the soldier on his back.

At the railway line, he rested and lowered Hector to the ground. A rictus had formed on the soldier’s face. James balanced Hector’s head on his lap, and worked the rictus away. Under the massaging of his fingers, the facial muscles relaxed, and the soldier took a deep breath, in the same way that a real man would do after the passing of a crisis.

James took out the soldier’s canteen and tried a sip of his water. It was faintly fizzy and doctored. Hector reached up for the canteen.

“Do you want this?” James searched Hector’s face for signs of volition. The hand hung there, waiting. He pressed the canteen into it. The soldier took a sip, his lips tight around the spout.

Smoke from the fires of the blacksmith of Glynde rose wispy black against the soft green of Mount Caburn. James checked the rope was secure around Hector’s midriff. He jogged down the railway cutting, the soldier stumbling after him.

The Hampden family still occupied the grand house of Glynde Place and their tenants in the surrounding cottages worked for the Institute much as laymen and laywomen had for the monasteries; acting as intermediaries between the secular and the sacred. With the railway closed, few outsiders came to the village. Cattle milled around the abandoned ticket office and the cricket pitch had been turned to allotments. The bailiff was known to the men and women digging in the field. Their evasive expressions paid James his due.

The blacksmith, smoking a roll-up cigarette in his yard, was the only one to catch his eye; a proud man whose choice of craft had once seemed quaint, even perverse. Not anymore.

“Is that a soldier, bailiff?” The blacksmith wiped his oily hands on his apron, squinting through cigarette smoke.

“Have you seen more of them?”

The blacksmith nodded. “I heard them marching down the lanes at night. The wooden wheels of their carts on the road. I took them for spectres, but the viscount reckons they’re made men and come from the factory out by Newhaven.”

“I saw ships, big container ships waiting in the bay.”

“Raw materials for the assemblers.” The blacksmith was a weathered tall man in his late fifties, cynical and houndish, with deeply scored features, bloodshot eyes and swollen fingers that indicated a neglected medical condition.

“The Process can make anything from a pattern but I’d be out of a job if it started making things that

original

.” The blacksmith wiped the oil from his hands with a rag and appraised James from head to toe.

“You’re not using the armour, bailiff?”

“Not today.”

“Is it broken again?”

During the Seizure, James had stood on this very grass, forty feet high in the armour, pistons hissing, iron fingers fashioned from digger’s claws, gearwheels turning in response to his every gesture, his voice an amplified fizzing bark, and asked the blacksmith for help.

“I keep the armour for evictions.”

“What if you run into trouble?”

“Have you heard of any trouble?”

“A few of the people you moved on from Newhaven came back.” The blacksmith pointed out the villagers working the allotment. “That family walked all the way from London. We took them in. There’s some work here, and some food.”

The soldier’s leash tightened and James staggered back a step.

“He wants to get back with his comrades,” said the blacksmith.

“Let me show you how he is put together.”

James yanked the rope hard so that the soldier sprawled once more on the earth. Quickly, James sat astride him, removed the bandage, and by the force of his thumbs parted the wound. The blacksmith whistled, set his cigarette aside and reached into the gash with the tip of a penknife, prising out one of the crimson seeds embedded in the man’s flesh. He held it up to the sunlight to observe how the light swirled within its translucency.

“A polymer seed. He’s been specially grown. His face is very individual, isn’t it?”

“His identity discs give his name as J Hector. Do you think he is a copy of an actual soldier?”

“His body is very slight. He’s about five foot nine, isn’t he? The Tommies were small men. As to whether he is a copy of somebody who actually lived, the Process has to work from an existing pattern. That means something or somebody who existed. The Institute will know for certain.”

The blacksmith left sooty fingerprints upon the soldier’s cheekbones. He slipped the seed into the breast pocket of his overall and offered James a drink. James declined. He had to push on to the Institute. It was only a matter of time before the Process made the soldier unmanageable.