Iconoclast: A Neuroscientist Reveals How to Think Differently (26 page)

Read Iconoclast: A Neuroscientist Reveals How to Think Differently Online

Authors: Gregory Berns Ph.d.

Tags: #Industrial & Organizational Psychology, #Creative Ability, #Management, #Neuropsychology, #Religion, #Medical, #Behavior - Physiology, #General, #Thinking - Physiology, #Psychophysiology - Methods, #Risk-Taking, #Neuroscience, #Psychology; Industrial, #Fear, #Perception - Physiology, #Iconoclasm, #Business & Economics, #Psychology

Innovation Diffusion

Iconoclasts deal in new ideas. They innovate and, ultimately, tear down existing institutions. When Jones introduced the Nautilus, he tore down the clubby bodybuilding world and opened up fitness to a much larger audience. But the process does not happen overnight. Like the opening of milk bottles, ideas that are ultimately accepted follow a well-described trajectory of adoption in society.

According to Everett Rogers, the first scientist to empirically study innovations and the originator of the field of study, there are five attributes of innovations.

3

Bear in mind that these attributes are not objective qualities but perceptions of potential users. First, the innovation must offer an

advantage

over existing products or ideas. Second, the innovation, although potentially novel, must still be

compatible

with existing value systems and social norms. Third, the

complexity

of the innovation will determine the rate at which it is adopted by other people. The more complex the innovation is, the lower the rate of adoption. Fourth, innovations should be

triable

. This allows potential users to try out the idea without much cost to themselves. Fifth, the results of the innovation must be

visible

to other people. Again, this allows potential users to judge the relative advantages of the innovation without having to try it out themselves. Although all five attributes are important, it is really the first two—advantageousness and compatibil-ity—that determine whether other people will adopt a particular innovation. These two attributes are also in tension with each other. The more advantageous an idea, the more it is potentially incompatible

with existing frameworks. The Nautilus offered a huge advantage in time and efficiency over barbells, and that immediately put it into conflict with the status quo. It is here, at the extreme end of incompatibility, that we find the iconoclasts like Jones.

Iconoclasts are also innovators because they create something new, and so there is much to be gleaned from the study of how innovations are accepted or rejected. When Everett Rogers wrote his groundbreaking book,

Diffusion of Innovations

, in 1962, social scientists had been using a wide range of terms to describe innovators. Terms such as

progressist, experimental, lighthouse

, and

advance scout

were thrown around. At the other end of the spectrum, people were often spoken of as

drones, sheep

, and

diehards

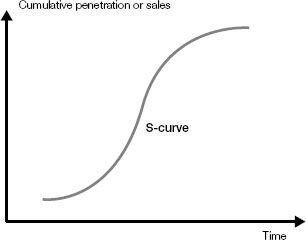

. Colorful terms to which you could relate, but they weren’t very precise. Rogers’s breakthrough came when he realized that all innovations, regardless of the technology, followed a characteristic pattern of adoption, called the

S-curve

(see figure 8-1). The S-curve describes the cumulative rate of adoption of a particular idea or technology as a function of time. Early in the life of an innovation, very few people use it. With time, however, the number of adopters

grows. For a time, the rate of growth itself increases so that the percentage of people adopting the idea accelerates. Eventually, the innovation becomes so widespread that accelerated growth is no longer sustainable, and the rate at which people adopt the idea slows down, eventually reaching zero.

FIGURE 8-1

S-shaped curve of the rate of diffusion of new ideas

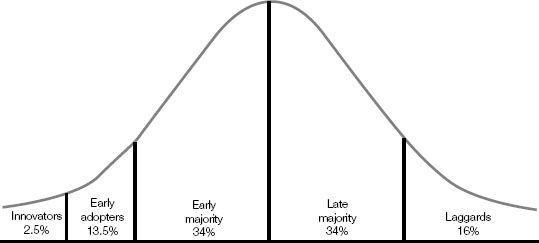

Rogers eschewed the use of imprecise descriptive labels for the different categories of adopters. Instead, he simply took a cue from standard statistical descriptions of personality traits. Any human attribute, whether it is physical height or IQ, is distributed to varying degrees in the population at large. When you plot the number of people possessing each value of the attribute, you come up with a normal distribution, commonly known as the bell curve because of its shape. The bell shape comes from the fact that most people possess the average value, and extreme values are relatively rare. Rogers realized that the trait of innovativeness also followed this distribution. Most people fell into what he called the

early majority

and

late majority

categories of adopters. Only the most extreme, which he defined as two standard deviations from the average and accounting for only 2.5 percent of the population, would fall into the category of true innovators (see figure 8-2).

FIGURE 8-2

Bell-curve distribution of the types of adopters in the population

Rogers did a neat trick. He realized that the S-curve resulted from integrating the bell curve of innovativeness. Integrating means adding up, in a cumulative fashion, the number of people in each category. Because the distribution of innovativeness describes

when

an individual adopts an idea, the integral of this distribution gives the S-curve of innovation diffusion, which is a graph of the number of adopters as a function of time.

This idea was given further mathematical precision by the Purdue finance professor Frank Bass. Bass said that there are really only two types of people:

innovators

and

imitators:

“Imitators, unlike innovators, are influenced in the timing of adoption by the decisions of other members of the social system.”

4

This is a subtle, but important, distinction from Rogers’s theory. Rogers offered a statistical argument for the rate at which innovations are adopted, but Bass offered a behavioral one. Bass said, “Innovators are not influenced in the timing of their initial purchase by the number of people who have already bought the product, while imitators are influenced by the number of previous buyers. Imitators

learn

from those who have already bought.” This means that the importance of innovators will be greater at first and diminish over time.

Jonas Salk and the Compatibility Factor

For rapid diffusion of ideas to occur, nothing beats compatibility. The first blue tit in Swaythling that discovered that he could skim the cream from the milk by piercing the foil top of the bottle was an innovator. This behavior, although novel, was completely compatible with his fellow birds’ behaviors. In fact, some have argued that the milk bottle opening wasn’t even an innovation, because it was simply an extension of the common motoric act of pecking at shiny things. But this is an unfair criticism. The behavior did not exist before the bottles, and so someone had to discover it. The reason it spread so quickly was because

the behavior was completely compatible with what birds normally do. It is the same for human innovations.

When Jonas Salk came on the scene to tackle polio in the 1950s, he entered a fierce competition. Polio, in more ways than one, had shaped the course of history in the United States. Polio is a highly infectious virus and enters the body through the mouth, either by eating contaminated food or incidentally on the hands. Once inside the body, the virus begins multiplying in the gastrointestinal tract, after which it spreads throughout the body. Most people experience polio as a flulike illness, and that’s the end of it, but about 1 percent of individuals experience much more severe symptoms. For these people, the virus enters the central nervous system and, for unknown reasons, attacks the nerves. The end result is paralysis.

In 1952, Salk decided to build on his experience with developing flu vaccines to tackle the holy grail of immunology and go for polio. Ever since Edward Jenner developed the smallpox vaccine, most immunologists believed that using a live virus was the most effective way to vaccinate an individual. The key to live vaccines depended on developing an attenuated version of the virus that actually caused the illness. Jenner used cowpox in place of smallpox. But there wasn’t any such thing for polio when Salk came on the scene. Instead, he took the other route and developed a vaccine made up of killed polio viruses. It wasn’t a particularly novel approach, but it was effective. Salk’s major rival, Albert Sabin, who was developing a live vaccine, derided Salk, famously remarking, “Salk was strictly a kitchen chemist. He never had an original idea in his life.”

5

Salk was an opportunist. He figured that the simplest approach would win the race, and this meant a killed virus vaccine. When he found out about a new technique that allowed him to grow large quantities of polio virus in a test tube, it was a simple matter to inactivate it by dunking the virus in formalin. The killed viruses, when injected in

diluted form, provoked an immune response that gave lasting protection against the real thing.

It wasn’t exactly rocket science, but Salk inadvertently benefited from the way in which ideas diffuse. Instead of waiting to publish his findings in a medical journal, which would have involved lengthy peer review from his competitors, he went straight to the public. On March 26, 1953, Salk appeared on CBS’s national radio program and announced his results. He would be vilified for this move by fellow scientists for the rest of his life. But the public, scared by polio outbreaks, was urgently ready to adopt a vaccine. Salk’s vaccine was particularly compatible with the existing social expectations. The public did not need to do anything different other than lining up for a shot, and they were already used to that. Salk became an icon overnight. And although he never won a Nobel Prize, he will always be indelibly linked to the cure for polio.

The key lesson from Salk’s vaccine is the power of compatibility. Timing is important, but the iconoclast cannot control the timing of discovery. He can, however, make his ideas as compatible with existing frameworks of thought as possible. Iconoclasts are used to seeing things differently than other people, but most of the public sees things in ways that are familiar to them. Thus, the transition from iconoclast to icon means that the iconoclast must present his ideas in a way that is familiar, even if they are not.

The Brains of Early Adopters

The birds’ discovery that they could skim the cream from milk bottles by opening the tops is an amazing story of animal adaptation. There is an even deeper question behind the story, however. Why was it that the blue tits discovered this and not some other bird? Why didn’t a pigeon figure this out? The fact that it was a tit and not some other bird yields

an important clue about the biological basis of innovative behavior and how new ideas diffuse through societies.

Fisher and Hinde opened the door to the study of bird behavior, especially the study of how they innovate. Over the next few decades, ecologists began to systematically measure the relationship between exploratory behavior, environment, and biology. In one such setup, a wild bird is captured and then given the choice between a familiar and a novel object. The degree of novelty seeking is measured by how long it takes the bird to approach the unfamiliar object relative to the familiar one. Birds that don’t like new things display characteristic signs of fear. Their feathers start to stand on end. Some species do jumping jacks, where they gingerly approach the new object and quickly make backward hops.

Unless you are an ornithologist or a bird aficionado, you probably don’t give much thought to bird brains. But like people, some birds are smarter than others, and the difference has much to do with their brains. For birds, the bigger the brain, the more likely a species will assimilate new ideas. But when it comes to human brain size, there are two schools of thought. One possibility is that humans evolved large brains to solve complex problems related to survival. A big brain, for example, let an early human discover that tools could be used to kill other animals. A big brain also has more memory capacity and would let its owner use the results of past events to predict the future. Compelling arguments, but there is another side to the story.