Icelandic Magic (6 page)

5

Runes and Magical Signs

The knowledge surrounding the ancient lore of the runes had decayed significantly by the sixteenth century. Nevertheless, the history of magic demonstrates that even confused forms can still be used effectively by skilled sorcerers. What most interests us here is the way in which runic magical methods and techniques were handed down in the Icelandic traditions. The two main distinctive graphic features of the Northern style are the use of runes and the magical signs. The runes (Ice.

rúnir

) or runelike symbols, or even magical letters or characters (Ice.

galdraletur

), were used liberally in Icelandic magical manuals, as were the magical signs known in Icelandic as either

galdrastafir

or

galdramyndir.

As we noted earlier, another striking feature is that the technique by which this magic was effected was often virtually identical with that of the rune magic employed in the pagan age.

Basic runelore is found in appendix A of this book, along with instructions on how to transliterate Old Norse names into authentic runic forms.

As a practical alternative script, the runes continued to be known in Iceland into modern times. They were sometimes used to write inscriptions in and around magical drawings, or to write certain words in spells that the magician wanted to obscure. There was also the use of encoded runic forms called

galdraletur, villuletur,

or

villurúnir.

These were meant to confuse and conceal rather than reveal meanings. Runelore was sometimes used by the magicians who composed or compiled these workings by having certain numbers of runelike figures arranged in a way suggestive of the runic system. For example, efforts were made to use a meaningful number of figures to compose complexes or series of signs, such that there are twenty-four or sixteen or eight of them.

The terminology for describing the magical figures and ways of using them was also inherited from ancient runic magical practice. Often these signs are referred to in Icelandic as

stafir

(sing.

stafur

), “staves.” This terminology is taken over from the old technical designation of runes as staves or “sticks.” This is because they were from an early time carved on such wooden objects originally used for talismanic or divinatory purposes. The execution of these figures for magical aims is indicated by the Icelandic verbs

rÃsta

or

rista,

both meaning “to carve, scratch, or cut.” At first these terms indicate that actual cutting or carving is intended (into wooden or stone objects, for example), but later they are also used in contexts that show that what is intended is more akin to

writing,

as with ink and quill on parchment or paper.

Certainly the most outstanding single feature of the Icelandic books of magic is the presence of complex magical signs. Most efforts at classifying these signs attempt to determine their relationships to the runes and their magical functions. There are three main types of such signs.

- Bandrúnir:

bindrunes made up of more or less obvious combinations of runes - Galdrastafir:

magic staves, which were perhaps originally bind runes but which have become so stylized as to take on independent lives of their own - Galdramyndir:

magical signs that seem to have always been non-runic, abstract, or iconic signs

Many of the signs appear to be combinations of runes and abstract symbols. The main problem that arises in any effort to decipher these signs is the longstanding tradition of stylization, which can include simplification as well as artificial complication or elaboration. Another way of

classifying them has to do with their functions. If they were intended

to be protective amulets they might be called by the Latin name

innsigli

(sigils) or by the Icelandic term

varnastafir

(protective staves). The term

galdrastafir

would then indicate magic of an operative nature meant to

cause alterations in the environment.

It is almost impossible to read any linguistic meaning in the

galdrastafir

(and many of the

bandrúnir

) without having some indication

being given in the commentaries. These leads usually come in the form

of the distinctive names given to particular signs. Examples of such

names are given in

figure 4.1

. Careful analysis reveals these

to be

bandrúnir

that have been stylized in the medium of pen and ink,

yet many of their runic features remain visible. On the other hand,

many of the names given to magical signs have to do with their functions

and not their forms. The names themselves are most often words

with highly obscure meanings. The two most famous names of such

signs are

ægishjálmur

(helm of awe or terror) and

and

svefnþorn

(sleepthorn) . The

. The

ægishjálmur

is a name given to a figure that could be

simple or extremely complex, but its basic form starts out as a fourfold

or eightfold equal-armed cross with branches at its terminals. With

these two signs we are lucky, because mythic narratives survive that give

us insights into their origins, contexts, and meanings.

The

ægishjálmur

is mentioned in Old Norse literature concerning

the legendary hero Sigurðr Fáfnisbani. When Sigurðr slays the serpent

named Fáfnir to gain the treasure hoard of the Niflungs (Nibelungen),

one of the objects of power that he obtains is the

ægishjálmur

. This is

not a “helmet” in the usual sense, but rather a general covering that

surrounds the wearer with an overawing power to terrify and subdue

any enemies. This power is portrayed as being concentrated between the

eyes, and it is often associated with the legendary power of serpents to

paralyze their prey. This is an ancient Indo-European concept, as demonstrated

by the etymology of the Greek drakônâthe “one with the evil

eye.” This is also reminiscent of the Gorgons' ability to paralyze their victims, to petrify or “turn them to stone,” with the gaze of their eyes set in a head surmounted by serpents.

The

svefnþorn

is also mentioned in Old Norse mythic literature as the magical device with which Ãðinn placed one of the

valkyrjur,

SigrdrÃfa (or Brynhildr), into a deep slumber from which she could be awakened only by one who was able to cross the magical barrier of fire placed around her by Ãðinn. This feat too was accomplished by the Odinic hero Sigurðr Fáfnisbani. Spells intended to put people into a deep slumber from which they can be awakened only by the magical will of the sorcerer are common in the Icelandic black books, and there are numerous signs that are given the name

svefnþorn

.

In addition to these two signs there are several other names given to signs, for example,

gapaldur, veðurgapi

(“weather daredevil,” to cause a storm),

kaupaloki

(“deal-closer,” for good business),

ginnir

(also a name of Ãðinn), and

angurgapi

(“reckless one of anger”). The fact that the same name may be attached to two or more different signs shows the names are not so much given to the particular shape of the sign but instead describe the sign's intended effect.

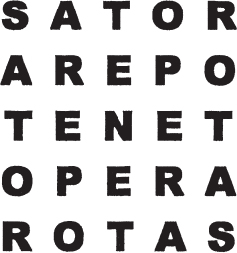

Despite the fact that it is obviously of Mediterranean origin, the so-called

sator

-square has certainly found a lively existence in the magical lore of the North. As a graphic sign it most often appears inscribed in Latin letters (see figure 5.1

below). The verbal formula was apparently well known, as magical instructions sometimes call for reciting the “

sator-arepo.

” It seems clear that this means that the practitioner is to speak the apparently nonsense sounds

sator-arepo-tenet-opera-rotas.

The

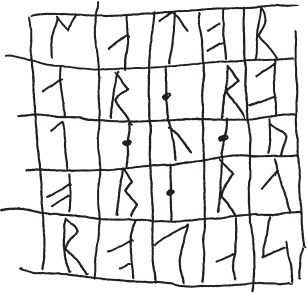

sator

-square formula was so well integrated into Northern practice that it is also found in at least nine runic inscriptions! One example is found on the bottom of a fourteenth-century silver bowl from Dune, Gotland (see figure 5.2, below).

Fig. 5.1. Sator-square

The

sator

-formula is actually one that conceals the formula Paternoster (“Our Father”) plus the formula “A + O” (

alpha

+

omega

). This formula is obviously best known as the beginning of the Christian “Lord's Prayer.” This prayer is widely used in magical contexts, but the formula actually predates Christianity. We know this because an example of the

sator

-square was found in the ruins of the Roman city of Pompeiiâburied under volcanic ash in the year 79 CE. This predates any known Christian influence in that city, and so it demonstrates that the “Our Father” prayer was used by some sect before the advent of organized Christianity. The sect in question was most likely the cult of Mithras from which organized Christianity adopted many features.

Fig. 5.2. Reproduction of the sator-square from the Dune bowl

6

The Theory and Practice of

Galdor-Sign Magic

Examples such as the

sator

-square point up the fact that there were definitely influences coming into the North from the southern European traditions of magic. But to some extent these examples serve also to show the remarkable degree to which basic Northern ideas of how magic works, and of how to work magic, remained intact even under this superficial influence.

We will now look at the underlying theories of magic as expressed in the Icelandic

galdrabækur,

at the powers by which it was thought to work, and at some of the consistent ritual techniques.

Standard medieval magical theories stemming from the Mediterranean and Middle East are based on a model in which lower entities are coerced by the agency of higher entities to fulfill the wishes of the magician. This usually involves long preparations, and the magician must also use specific ritual procedures to ensure protection from the entities that he invokes. After the rite the magician formally banishes the spirits he has invoked. There are certain aspects of this theoretical working model that remain foreign to the Icelandic magician. In Icelandic magic it is rare to see any extensive preparations indicated for a specific working; instead it appears that the magician constantly prepared himself in a general way and then applied his spells almost in a rough-and-ready fashion. This is very reminiscent of the way Egill SkallagrÃmsson worked. Furthermore, the Icelandic magician never seems to need to protect himself from the powers upon which he is calling; to the contrary, he appears more concerned with the actions of other humans. Although spiritual entities are involved, it would be more accurate to say that they

help

the magician work his own will rather than do the work for himâand because the magician has no need to protect himself from the entities he summons, he has no need to banish them.

Generally speaking, Icelandic magic seems to have worked through one of three media: (1) graphic signs, (2) spoken or written words, and (3) natural substances. These media could be used alone or in combination with one another.

Graphic signs (including runes and other written or drawn characters) are thought to be conduits or doorways through which various impersonal powers or personalized entities are directed in order to facilitate the will of the magician. The actual physical sign seems to have little power on its own; it is only in combination with the will of a trained magician that any results can be expected. That is why, in the folktales concerning the famous

galdramenn,

such emphasis is placed on their scholarly characters and on the fact that signs had to be learned by a process that apparently involved more time and effort than just memorizing their external forms. Nevertheless, the memorization of their forms was likely the first step in this process. Except for the most common signs such as the

ægishjálmur

or the

Ãórshamar,

specific “staves” rarely appear more than once among the various manuscripts. The fact that quite different staves might be called by the same name, however, indicates that it was an inner formârather than an external shapeâthat was mainly being “learned.”

Words, whether spoken or written, are the medium often used to activate the signs. Words can work alone either to direct or command some power or entity or to beseech an entity to act on behalf of the magician. The latter prayer-type formula is usually found only in spells of a Christianized kind. In the medieval Icelandic formularies words and names can activate the corresponding power or entity in a way desired by the magician and as formulated in his verbal spell. The “power of the name” is a well-known phenomenon in the annals of magic, and such a belief was also part of the ancient Germanic worldview. Its most famous depiction is in the lore surrounding Sigurðr Fáfnisbani: after fatally wounding the serpent Fáfnir, Sigurðr attempts to conceal his name from the dying giant because, as we read in the “Fáfnismál,” a poem from the

Poetic Edda,

“it was the belief in olden times that the words of a doomed man had great might, if he cursed his foe by name.”

*12

This ancient Germanic lore was, of course, further reinforced by the importation of Judeo-Gnostic names of God or words of power that are heaped up in some of the Christian-type spells. In all cases these verbal elements are seen as being vitally linked to the actual things they name, and therefore willful and trained manipulation of such words and names constitutes a manipulation of the actual things or entities.

Certain substances tend to be used in magical operations, the most typical being blood and woods of various kinds. Both are well represented in the heathen type of spell. The blood of the magician can be used, and in the old material four kinds of woodâoak, rowan, alder, and ashâare frequently mentioned. Herbs are also referenced in many old spells. The most useful are

millefolium

(yarrow) and

Frigg jargras

(

Platanthera hyperborea

). Many other spells make use of various substances on which staves are to be carved or written. In each case there seems to be an underlying analogical reason for the use of the substance, which must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

In Icelandic magical spells emphasis is laid heavily on the person of the magician. He is rarely said to have the explicit help of outside forces, and the rituals, such as they are, are quite simple procedures. This is, again, a sharp contrast to the multilateral complexities found in grimoires of the southern tradition.

Because there is such a strong emphasis placed on the person of the magician, it is necessary to take a closer look at what makes up the psychophysical complex of the individual human being. We can know this to a fairly exact degree because they had such a well-developed set of technical terms for the psyche. In pagan times this body-soul structure could have been described as having

- a physical body (ON

lÃk

) - a shape or semiphysical body image (ON

hamr

) - a faculty of inspiration (ON

óðr

) - a vital breath (ON

önd

) - a volitive/cognitive/perceptive faculty (ON

hugr

) - a reflective faculty (ON

minni

) - a “shade,” or after-death, image (ON

sál

or, figuratively,

skuggi,

“shadow”) - a permanent magical soul or fetch (ON

fylgja

) - a dynamistic empowering substance that gives luck, protection, and the ability to shape-shift (ON

haming ja

)

Unfortunately, with the coming of Christianity, this refined native psychology, or “soul lore,” was assailed and began to decay and became very confused and stunted. In our

galdrabækur

we have only the remnants of a fragmented system. Nevertheless, it is clear that the Icelandic magicians preserved some of the technical lore in ways they believed magic worked. It seems fairly clear that even in the period in which those spells were being used the magicians recognized (1) an animating or vital principle, (2) a personal image, (3) a separable power entity by which “sendings” (Ice.

sendingar

) were projected, and (4) an essential core faculty of “heart and mind” (Ice.

hugur

).

For example, it is obvious that curse formulas are meant to deplete the vital energy of a person or animal, and protective formulas are meant to build up this faculty. Other formulas are intended to change the quality of the contents of the

hugur

âfor example, to cause someone to fear or love the magician. The ability to see shades, or images, of other people, especially ones who have stolen something from the magician, is also frequently mentioned.

For the form of magic outlined in the practical parts of this book some command over these faculties must first be developed. Without this development the words and signs are mere empty shells that await vivification by the faculties of a developed magician.

Spell 34 in the

Galdrabók,

adapted in this book as a spell to acquire love, represents a working to get the love of a woman. It is an attempt to turn her free will genuinely toward the magician, but it is couched in the magical forms of threats and curses. A review of the magical procedures would include a complex set of actions. First, the woman's being is linked to the formula by means of location (placing the staves and material components of the spell “in a place where she will go over it”) and essence (writing her name with staves); then the magician's (sexual) being is linked with the woman's being and with the magical formulas by means of the “etin-spear blood” (“snake blood,” that is, semen); and finally, the magical signs that graphically embody the aim of the operation are inscribed and the whole contained in a ring of water. All of this has linked the woman, the magician, and the aim in an essential but as yet only general way. This symbolic and graphic series of actions and signs is then empowered and given a specific direction by means of the words spoken over the forms. This spell includes references to how the formula is to work within the psychological scheme as understood by the magician. It includes graphic imagery and a prayerlike entreaty to Ãðinn for success. (In the ancient mythology, Ãðinn is, by the way, known for his interest in spells of this kind.) Just about all of the elements common to medieval Icelandic spells are to be found in this operation, and again, it should not be missed that the general procedure is quite the same as that practiced by the pagan runic magicians of the North.

Ultimately it must be said that the theory of galdor-sign magic is one in which there is a system of communication between the magician and the causal powers of the universe. All systems of communication have their own language, and hence grammar, by which precise messages can be sent and received by the various parties involved. If this language is learned, the code of grammar and vocabulary is “cracked”; the magician is then free to conduct his or her own communications as desired. Here we learn to communicate with causal powers through the signs: we send messages in signs and the universe responds with events, either inner or outer ones in ourselves or in the minds of others. We basically do this in a manner similar to the way we learn and speak our own native languages of natural communication. The first step is to observe how the process works. This is then followed by a period of imitating the successful communications of others, after which we can begin to finally communicate on our own, in ways that are effective for us. This book guides you through the first two levels of this process and shows you a glimpse of the third. But the third level is one that must be undertaken independently.

Languages are made up of increasingly complex levels of signs. At the base level we start with phonology, the understanding of the system of basic

sounds

in the language. The next level is morphology, the understanding of the meaningful clusters into which sounds can be arranged, basically what we call “words.” Syntax is the next level, which has to do with the arrangement of words in meaningful strings to convey a more complex communication: the sentence. Galdor signs work in a similar way, just in more dimensions than natural language. In chapter 9 of this book we will go into the practical aspects of this grammar of the galdor signs.