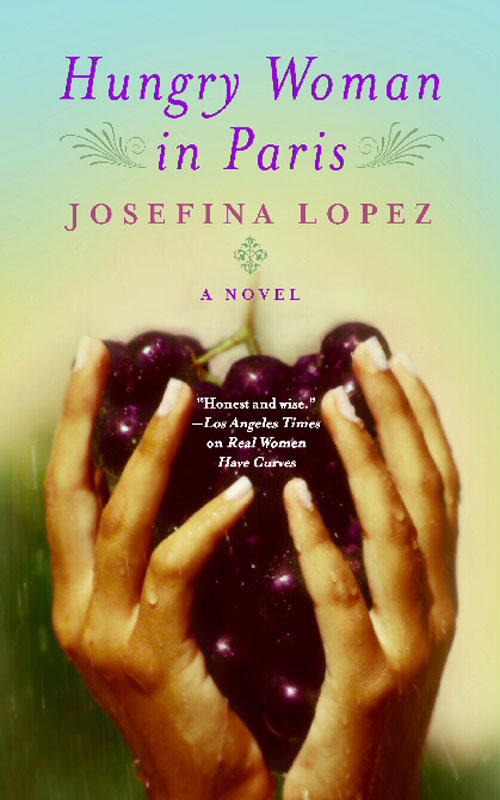

Hungry Woman in Paris

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are

used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2009 by Josefina López

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook Edition: March 2009

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-446-54446-7

Contents

Chapter 1: Four Gossips and a Funeral

Chapter 3: Hiding Out in the Sixteenth

Chapter 4: Bonjour, Carte de Séjour

Chapter 6: Like Water for Canela

Chapter 7: I’ll Always Have Butter

Chapter 10: Blood of the Earth

Chapter 11: Eat Woman Drink Man

Chapter 12: Alive and Rotting in Paris

Chapter 14: Not Without My Bag!

Chapter 15: Boys in the Banlieue

Chapter 18: Au Revoir les Euros

Chapter 19: Last Mango in Paris

Glossary of French and Spanish Words and Terms

This book is dedicated to my parents, Catalina and Rosendo López, who lived their lives in the United States as immigrants

with dignity and sacrificed so much to give their children an education and a better life; and to my brothers and sisters,

who all have become exemplary models of successful American citizens.

This book is also dedicated to all the women I met at cooking school—in particular, Amy Whitman, Carla Trujillo, Kate Moffet,

Myra Coca, Ingrid Wright, Sofia Sarabia—and to all the women in cooking schools who aspire to be taken seriously as chefs.

May the fire in their hearts continue to burn bright.

To my husband, Emmanuel, who gave me a wonderful introduction to French culture and continues to surprise me by aspiring to

be the man of my dreams.

To my dear cousin Marina, whom I never got to know because there was a border between us, but whose tragic passing haunts

me.

This novel and my career were made possible by my wonderful and passionate manager, Marilyn Atlas.

I would also like to thank my literary agent Barbara Hogenson for being so lovely to work with.

My editor, Selina, took my underwritten and overplotted story and helped shape it into a real novel. Thank you!

I also want to thank all the other editors who worked on my novel for helping me clarify my story and making me sound articulate

in three languages. Gracias! Merci! Thank you!

I couldn’t have survived Le Cordon Bleu cooking school without the kindness and support of Kate Moffet, Myra Coca, Carla Trujillo,

and Christopher Carlos.

I also want to acknowledge all the sweet ladies in administration at Le Cordon Bleu for being extra kind to Americans, as

well as Chef Didier, for always bringing joy and passion to the kitchen.

Thank you to all my muses and friends who encouraged me along the way: my sweet mother, Miles Brandman, Luz Vasquez, Hector

Rodriguez, Mercedes Floresislas, Patricia Zamorano, Margarita Medina, Elizabeth Andrews, Angela Wu, Anthony Villareal, Jay

Vincent, Rafael Rubalcava, Jeremy Ackers, Anaïs Nin, Stephen Clarke for writing

A Year in the Merde,

Alisa Valdes-Rodriguez for showing me it could be done, and Sandra Cisneros for clearing the path for Latina writers like

me.

Thank you to all the Latina journalists who serve as inspiration for this novel, in particular Yvette Cabrera, Christina Gonzalez,

Lorena Mendez, and Elizabeth Espinoza.

A very special thanks to Angel Alcala, who planted the seed in my mind to go to Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, as well as Jennifer

Ladder, who had the courage to follow her heart and inspired me to enroll in cooking school too.

T

T

his is either the longest suicide note in history or the juiciest, dirtiest, most delicious confession you’ll ever hear. Call

me Canela. That’s Spanish for Cinnamon, but don’t call me Cinnamon; that’s a stripper’s name. Not that there is anything wrong

with being an exotic dancer. With my lifestyle, I’m the last one to throw stones. Thank God I’m a modern woman living in a

so-called democracy and—aside from in Nigeria and some Middle Eastern countries I would be too scared to visit—getting killed

by stones is a thing of the past. My mother named me Canela because she loved to make buñuelos and add lots of sugar and cinnamon

to them. She would make them from scratch, using none of the shortcuts, like taking flour tortillas and frying them. You do

know what a tortilla is, don’t you? By now who doesn’t? No, she did them by hand,

a mano.

It was probably her sweat and tears that made them tasty. When she saw me for the first time, she was disappointed that I

was so pale. Unlike some Mexicans with internalized racism, she thought being dark and indigenous- looking was beautiful,

but she wondered if people gossiped about whether she had cheated on my father with an American to get such a white-looking

child. I did get her high cheekbones, big eyes, big breasts, black hair, and love of smells. I also got her propensity to

be fat, but let’s not talk about that right now. My mother spent most of her time in the kitchen and in the bedroom. When

she wasn’t making beans, she was making babies. Her world was tiny, as was her kitchen, but she made it delicious. So by adding

cinnamon to a buñuelo she would make it even browner. With my name she spiced me up and made me brown. She didn’t want people

to mistake me for Italian or Irish—not that there’s anything wrong with that—so she gave me a Spanish name so people would

ask, “What is Canela?” More importantly, I hope you ask, Who is Canela? Who is Canela? Thanks for asking… My psychiatrist

might have an idea. My psychic might have a better idea. My mother probably has a good idea, but after thirty years in my

skin and in my soul, I’m still finding out…

Four Gossips and a Funeral

A

A

re you ready to begin your exciting culinary career?” the cooking school admissions agent asked me in her French-accented

English. I stared blankly up at her, clutching my admissions application, not believing what I was about to do. Anyone who

knew me would think I had clearly gone insane. But what had brought me here? It had never been my dream to attend Le Coq Rouge,

the world’s most famous cooking school. Yet here I was in Paris about to lay down thirty thousand dollars to be in the kitchen

when I had sworn I would never go back there, ever.

Maybe my mother was right: I had gone crazy and I needed medication. Otherwise why would I have broken off my engagement to

a Latino surgeon, given up my journalism career, and run off to Paris by myself?

“Is there a problem?” Marie-Hélène, the admissions agent, asked with half a smile.

“Ah…” I tried to come up with a line to buy me a few more seconds. I needed to think about my past and whether I was

making the right decision.

Maybe it was Luna’s suicide that had shaken me out of my senses, or the Iraq war, or the fight with the editor, or the fight

with my fiancé, or my mother and father fighting… yes, when all else fails blame it on my childhood. All I knew was that

I didn’t want to go back to the United States, to my home in Los Angeles, and this was the only way to stay in France.

It must have been the fight at the wake that made me realize I was exhausted from fighting everyone, including myself.

Why is it that when someone dies everyone only says good things about her at the funeral? Death makes angels of everyone,

I suppose. No, I think it’s out of superstition. At the root of every fear is death, so if you speak badly of someone who

is dead and they can’t defend themselves, then death might strike you. At my funeral I want people to say I was a bitch if

I truly was one to them. All I hope is that the people who experienced my kindness will speak up and say, “Yes, but…”

Maybe then people can have authentic conversations instead of the stupid ones in which everyone knows the person is dead but,

aside from this exception, pretends death doesn’t really exist, thus freeing them to converse about silly things. Silly things

like my broken-off engagement.

“Is it true what I just heard?” asked my mother in her metiche mode. My mother was usually my favorite person on the planet,

but also the one that drove me to tears and insanity at the push of an emotional button whose location only she knew.

“You hear a lot of things, including ghosts, so it depends on what you heard,” I replied.

“You and Armando—what’s going on?” she demanded to know. “Your sister told me she thinks you are depressed. I think you should

get on medication. You are not thinking straight. You can’t break it off. He’s a doctor and he loves you! Do you realize how

hard it is to get a good man in Los Angeles? Es una locura!” she hissed at me like a cat about to get mauled by a dog.