How We Learn (23 page)

Authors: Benedict Carey

The incorporation of these random demands is what made Kerr and Booth’s observation plausible, and Schmidt and Bjork knew well enough that the principle wasn’t only applicable to physical skills. Digging out verbal memories on a dime requires a mental—if not physical—suppleness that doesn’t develop in repetitive practice as fast as it could. In one previous experiment, Bjork and T. K. Landauer of Bell Laboratories had students try to memorize

a list of fifty names. Some of the names were presented for study and then tested several times in succession; other names were presented once and tested—but the test came

after

the study session was interrupted (the students were given other items to study during the interruption). In other words, each student studied one set of names in an unperturbed session and the other set in an interrupted one. Yet thirty minutes later, on subsequent tests, they recalled about 10 percent more of the names they’d studied on the interrupted schedule. Focused, un-harried practice held them back.

“It has generally been understood that any variation in practice that makes the information more immediate, more accurate, more frequent, or more useful will contribute to learning,” Schmidt and Bjork wrote. “Recent evidence, however, suggests that this generalization must be qualified.”

“Qualified” was a polite way to say “reconsidered” and possibly abandoned altogether.

It’s not that repetitive practice is

bad

. We all need a certain amount of it to become familiar with any new skill or material. But repetition creates a powerful illusion. Skills improve quickly and then plateau. By contrast, varied practice produces a slower

apparent

rate of improvement in each single practice session but a greater accumulation of skill and learning over time. In the long term, repeated practice on one skill slows us down.

Psychologists had been familiar with many of these findings, as isolated results, for years. But it was Schmidt and Bjork’s paper, “New

Conceptualizations of Practice,”

published in 1992, that arranged this constellation of disparate pieces into a general principle that can be applied to all practice—motor and verbal, academic as well as athletic. Their joint class turned out not to be devoted to contrasts, after all, but to identifying key similarities. “We are struck by the common features that underlie these counterintuitive phenomena in such a wide range of skill-learning situations,” they concluded. “At the most superficial level, it appears that systematically altering practice so as to encourage additional, or at least different, information processing activities can degrade performance during practice, but can at the same time have the effect of generating greater

performance capabilities.”

Which activities are those? We’ve already discussed one example, in

chapter 4

: the spacing effect. Breaking up study time is a form of interference, and it deepens learning without the learner investing more overall time or effort. Another example, explored in

chapter 3

, is context change. Mixing up study locations, taking the books outside or to a coffee shop, boosts retention. Each of these techniques scrambles focused practice, also causing some degree of forgetting between sessions. In their Forget to Learn theory, Robert and Elizabeth Bjork called any technique that causes forgetting a “desirable difficulty,” in that it forces the brain to work harder to dig up a memory or skill—and that added work intensifies subsequent retrieval and storage strength (learning).

But there’s another technique, and it goes right back to the long-lost beanbag study. Remember, the kids who did best on the final test hadn’t practiced on the three-foot target at all. They weren’t continually aiming at the same target, like their peers, doing a hundred A-minor scales in a row. Nor were they spacing their practice, or changing rooms, or being interrupted by some psychologist in a lab coat. They were simply alternating targets. It was a small variation, only a couple of feet, but that alteration represents a large idea, and

one that has become the focus of intense study at all levels of education.

• • •

Let’s leave the beanbags and badminton behind for now and talk about something that’s more likely to impress friends, strangers, and potential mates: art. I’m not talking about creating art, I’m talking about appreciating it. One of the first steps in passing oneself off as an urbane figure (so I’m told) is having some idea who actually created the painting you’re staring at. Remarking on Manet’s use of light while standing in front of a Matisse can blow your cover quickly—and force a stinging retreat to the information desk for some instructional headphones.

Yet learning to identify an artist’s individual touch, especially one who has experimented across genres and is not among history’s celebrities, a van Gogh or a Picasso or an O’Keeffe, is not so easy. The challenge is to somehow feel the presence of the artist in the painting, and there’s no simple recipe for doing so. What’s the difference between a Vermeer, a de Heem, and a van Everdingen, for example? I couldn’t pick any one of these Dutch masters out of a lineup, never mind identify the creative signatures that separate one from the others. “The different subjects chosen by Vermeer and de Heem and van der Heyden and van Everdingen are at once different ways of depicting life in 17th-Century Holland and different ways of expressing its domestic quality,” wrote the American philosopher Nelson Goodman in one of his essays on artistic style. “Sometimes features of what is exemplified, such as color organizations, are ways of exemplifying other features,

such as spatial patterns.”

Got all that? Me neither.

Goodman famously argued that the more elusive and cryptic an artist’s style, the more rewarding it was for the viewer: “An obvious style, easily identified by some superficial quirk, is properly decried as

a mere mannerism. A complex and subtle style, like a trenchant metaphor, resists reduction to a literal formula.” And there’s the rub. Art appreciation is a world removed from biology, playing music, German 101, and the epic poets. There are no word pairs or chemical bonds to study, no arpeggios or verses or other basic facts, no obvious verbal or motor “tasks” to measure. The ability contains an element of witchcraft, frankly, and learning scientists had traditionally left the study of artistic styles to the likes of academics like Goodman.

That all changed in 2006, when Robert Bjork and postdoctoral student Nate Kornell, now at Williams College, decided to test whether a form of interrupted study affected aesthetic judgment in addition to retention. The idea came from a story that one of Bjork’s colleagues had told him, about taking a trip to Italy with her teenage daughter. She—the mother—was excited by the opportunity to visit great museums, such as the Uffizi and Accademia in Florence, the National and Borghese in Rome, as well as the vast Vatican collection, but she worried that the experience would be lost on her daughter, if not actively resisted. She told Bjork that she knew her daughter would get so much more out of the trip if she learned to identify Italian painters’ styles—and had devised a flashcard game that taught her to do just that.

Kornell and Bjork did essentially

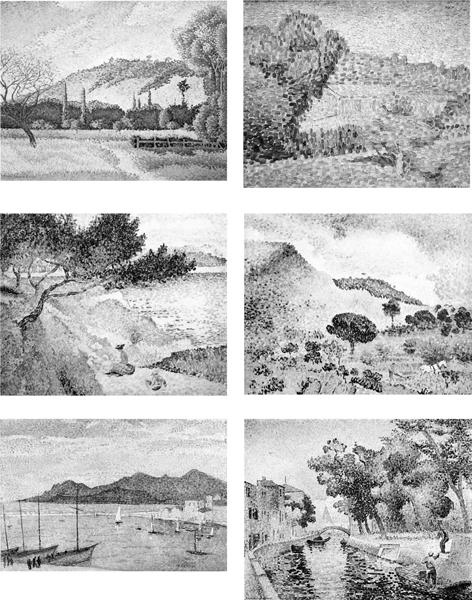

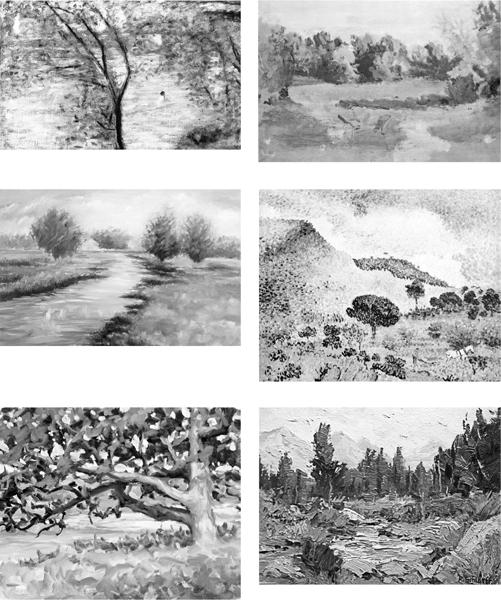

the same thing in their experiment. They chose a collection of paintings by twelve landscape artists, some of them familiar (Braque, Seurat), but most by artists unfamiliar to the participants, like Marilyn Mylrea, YeiMei, and Henri-Edmond Cross. They then had a group of seventy-two undergraduates study the paintings on a computer screen. Half of the students studied the artists one at a time. For example: They saw one Cross after another for three seconds each, with the name of the painter below the image:

After six Crosses, they saw (let’s say) six works by Braque, again for three seconds each with the artist’s name below; then six by YeiMei; and so on. Kornell and Bjork called this blocked practice, because the students studied each artist’s works in a set.

The other half of the participants studied the same paintings for the same amount of time (three seconds per piece), also with the artist’s name below. But in their case, the paintings were

not

grouped together by artist; they were mixed up:

Both groups studied a total of six paintings from each of the twelve artists. Which group would have a better handle on the styles at the end?

Kornell and Bjork had the participants count backward from 547 by threes after studying—a distraction that acted as a palette cleanser, a way to clear short-term memory and mark a clean break between the study phase and the final test. And that test—to count as a true measure of performance—could not include any of the paintings just studied. Remember, the participants in this study were trying to

learn painting

styles

, not memorize specific paintings. If you “know” Braque, you should be able to identify his touch in a painting of his you’ve never seen before. So Kornell and Bjork had the students view forty-eight un-studied landscapes, one at a time, and try to match each one to its creator, by clicking on one of the twelve names. The researchers weren’t sure what to expect but had reason to suspect that blocked study would be better. For one thing, no one understands exactly how people distinguish artistic styles. For another, similar studies back in the 1950s, having subjects try to learn the names of abstract drawings, found no differences. People studying the figures in blocked sets did every bit as well as those studying mixed sets.

Not this time. The mixed-study group got nearly 65 percent of the artists correct, and the blocked group only 50 percent. In the world of science, that’s a healthy difference, so the researchers ran another trial in a separate group of undergraduates to double-check it. Once again, each student got equal doses of blocked and mixed study: blocked for six of the artists, mixed for the other six. The result was the same: 65 percent correct for those studied in mixed sets, and 50 percent for those studied in blocks. “A common way to teach students about an artist is to show, in succession, a number of paintings by that artist,” Kornell and Bjork wrote. “Counterintuitive as it may be to art history teachers—and our participants—we found that interleaving paintings by different artists was more effective than massing all of an artist’s paintings together.”

Interleaving

. That’s a cognitive science word, and it simply means mixing related but distinct material during study. Music teachers have long favored a variation on this technique, switching from scales, to theory, to pieces all in one sitting. So have coaches and athletic trainers, alternating endurance and strength exercises to ensure recovery periods for certain muscles. These philosophies are largely rooted in tradition, in a person’s individual experience, or in concerns about overuse. Kornell and Bjork’s painting study put interleaving on the map as a

general

principle of learning, one that could

sharpen the imprint of virtually any studied material. It’s far too early to call their study a landmark—that’s for a better historian than I to say—but it has inspired a series of interleaving studies among amateurs and experts in a variety of fields. Piano playing. Bird-watching. Baseball hitting. Geometry.

What could account for such a big difference? Why any difference at all? Were the distinctions between styles somehow clearer when they were mixed?

In their experiment, Kornell and Bjork decided to consult the participants. In a questionnaire given after the final test, they asked the students which study method, blocked or interleaved, helped them learn best. Nearly 80 percent rated blocked study as good or better than the mixed kind. They had no sense that mixed study was helping them—and this was

after

the final test, which showed that mixing provided a significant edge.

“That may be the most astounding thing about this technique,” said John Dunlosky, a psychologist at Kent State University, who has shown that interleaving accelerates our ability to distinguish between bird species. “People don’t believe it, even after you show them they’ve done better.”

This much is clear: The mixing of items, skills, or concepts during practice, over the longer term, seems to help us not only see the distinctions between them but also to achieve a clearer grasp of each one individually. The hardest part is abandoning our primal faith in repetition.