How We Learn (12 page)

Authors: Benedict Carey

Why spaced study sessions have such a large impact on learning is still a matter of debate. Several factors are likely at work, depending on the interval. With very short intervals—seconds or minutes, as in the early studies—it may be that the brain becomes progressively less interested in a fact when it’s repeated multiple times in rapid succession. It has just heard, and stored, the fact that James Monroe was the fifth president. If the same fact is repeated again, and then a third time, the brain pays progressively less attention.

For intermediate intervals of days or weeks, other factors might come into play. Recall the Forget to Learn theory, which holds that forgetting aids learning in two ways: actively, by filtering out competing facts, and passively, in that some forgetting allows subsequent practice to deepen learning, like an exercised muscle.

The example we used in

chapter 2

was meeting the new neighbors for the first time (“Justin and Maria, what great names”). You

remember the names right after hearing them, as retrieval strength is high. Yet storage strength is low, and by tomorrow morning the names will be on the tip of your tongue. Until you hear, from over the hedges—“Justin! Maria!”—and you got ’em, at least for the next several days. That is to say: Hearing the names again triggers a mental act, retrieval

—Oh that’s right

,

Justin as in Timberlake and Maria as in Sharapova

—which boosts subsequent retrieval strength higher than it previously was. A day has passed between workouts, allowing strength to increase.

Spaced study—in many circumstances, including the neighbor example—also adds contextual cues, of the kind discussed in

Chapter 3

. You initially learned the names at the party, surrounded by friends and chatter, a glass of wine in hand. The second time, you heard them yelled out, over the hedges. The names are now embedded in two contexts, not just one. The same thing happens when reviewing a list of words or facts the second time (although context will likely be negligible, of course, if you’re studying in the same place both days).

The effects described above are largely subconscious, running under the radar. We don’t notice them. With longer intervals of a month or more, and especially with three or more sessions, we begin to notice some of the advantages that spacing allows, because they’re obvious. For the Bahricks, the longer intervals helped them identify words they were most likely to have trouble remembering. “With longer spaces, you’re forgetting more, but you find out what your weaknesses are and you correct for them,” Bahrick told me. “You find out which mediators—which cues, which associations, or hints you used for each word—are working and which aren’t. And if they’re not working, you come up with new ones.”

When I first start studying difficult material that comes with a new set of vocabulary (new software, the details of health insurance, the genetics of psychiatric disorders), I can study for an hour and return the next day and remember a few terms. Practically nothing.

The words and ideas are so strange at first that my brain has no way to categorize them, no place to put them. So be it. I now treat that first encounter as a casual walk-through, a meet-and-greet, and put in just twenty minutes. I know that in round two (twenty minutes) I’ll get more traction, not to mention round three (also twenty minutes). I haven’t used any more time, but I remember more.

By the 1990s, after its long incubation period in the lab, the spacing effect had grown legs and filled out—and in the process showed that it had real muscle. Results from classroom studies continued to roll in: Spaced review improves test scores for multiplication tables, for scientific definitions, for vocabulary. The truth is, nothing in learning science comes close in terms of immediate, significant, and reliable improvements to learning. Still, “spacing out” had no operating manual. The same questions about timing remained: What is the optimal study interval

given the test date

? What’s the timing equation? Does one exist?

• • •

The people who have worked hardest to turn the spacing effect into a practical strategy for everyday learning have one thing in common: They’re teachers, as well as researchers. If students are cramming and not retaining anything, it’s not all their fault. A good class should make the material stick, and spaced review (in class) is one way to do that. Teachers already do some reviewing, of course, but usually according to instinct or as part of standard curriculum, not guided by memory science. “I get sick of people taking my psych intro class and coming back next year and not remembering anything,” Melody Wiseheart, a psychologist at York University in Toronto, told me. “It’s a waste of time and money; people pay a lot for college. As a teacher, too, you want to teach so that people learn and remember: That’s your job. You certainly want to know when it’s best to review key concepts—what’s the best time, given the spacing effect, to revisit material? What is the optimal schedule for students preparing for a test?”

In 2008, a research team led by Wiseheart and Harold Pashler, a psychologist at the University of California, San Diego, conducted a large study that provided the

first good answer to those questions. The team enrolled 1,354 people of all ages, drawn from a pool of volunteers in the United States and abroad who had signed up to be “remote” research subjects, working online. Wiseheart and Pashler’s group had them study thirty-two obscure facts: “What European nation consumes the most spicy Mexican food?”: Norway. “Who invented snow golf?”: Rudyard Kipling. “What day of the week did Columbus set sail for the New World in 1492?”: Friday. “What’s the name of the dog on the Cracker Jack box?”: Bingo. Each participant studied the facts twice, on two separate occasions. For some, the two sessions were only ten minutes apart. For others, the interval was a day. For still another group, it was a month. The longest interval was six months. The researchers also varied the timing of the final exam. In total, there were twenty-six different study-test schedules for the researchers to compare.

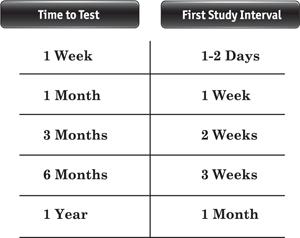

The researchers compared all twenty-six different study schedules, and calculated the best intervals

given different test dates

. “To put it simply, if you want to know the optimal distribution of your study time, you need to decide how long you wish to remember something,” Wiseheart and

Pashler’s group wrote. The optimal interval ranges can be read off a simple chart:

Have a close look. These numbers aren’t exact; there’s wiggle room on either side. But they’re close. If the test is in a week, and you want to split your study time in two, then do a session today and tomorrow, or today and the day after tomorrow. If you want to add a third, study the day before the test (just under a week later). If the test is a month away, then the best option is today, a week from today (for two sessions); for a third, wait three more weeks or so, until a day before the test. The further away the exam—that is, the more the time you have to prepare—the larger the optimal interval between sessions one and two. That optimal first interval declines as a

proportion

of the time-to-test, the Internet study found. If the test is in a week, the best interval is a day or two (20 to 40 percent). If it’s in six months, the best interval is three to five weeks (10 to 20 percent). Wait any longer between study sessions, and performance goes down fairly quickly. For most students, in college, high school, or middle school, Wiseheart told me, “It basically means you’re working with intervals of one day, two days, or one week. That should take care of most situations.”

Let’s take an example. Say there’s a German exam in three months or so at the end of the semester. Most of us will spend at least two months of that time learning what it is we

need

to know for the exam, leaving at most a few weeks to review, if that (graduate students excepted). Let’s say fifteen days, that’s our window. For convenience, let’s give ourselves nine hours total study time for that exam. The optimal schedule is the following: Three hours on Day 1. Three hours on Day 8. Three hours on Day 14, give or take a day. In each study session, we’re reviewing the same material. On Day 15, according to the spacing effect, we’ll do at least as well on the exam, compared to nine hours of cramming. The payoff is that we will retain that vocabulary for

much

longer, many months in this example. We’ll do far better on any subsequent tests, like at the beginning of the following semester. And we’ll do far better than cramming if the

exam is delayed a few days. We’ve learned at least as much, in the same amount of time—and it sticks.

Again, cramming works fine in a pinch. It just doesn’t last. Spacing does.

Yes, this kind of approach takes planning; nothing is entirely free. Still, spaced-out study is as close to a freebie as anything in learning science, and very much worth trying. Pick the subject area wisely. Remember, spacing is primarily a retention technique. Foreign languages. Science vocabulary. Names, places, dates, geography, memorizing speeches. Having more facts on board could very well help with comprehension, too, and several researchers are investigating just that, for math as well as other sciences. For now, though, this is a memorization strategy. The sensually educated William James, who became the philosopher-dean of early American psychology, was continually doling out advice about how to teach, learn, and remember (he didn’t generally emphasize the tutors and fully subsidized travel he was lucky enough to have had). Here he is, though, in his 1901 book

Talks to Teachers on Psychology: And to Students on Some of Life’s Ideals

, throwing out a whiff of the spacing effect: “Cramming seeks to stamp things in by intense application before the ordeal. But a thing thus learned can form few associations. On the other hand, the same thing recurring

on different days

in different contexts, read, recited, referred to again and again, related to other things and reviewed, gets well

wrought into mental structure.”

After more than a hundred years of research, we can finally say which days those are.

Chapter Five

The Hidden Value of Ignorance

The Many Dimensions of Testing

At some point in our lives, we all meet the Student Who Tests Well Without Trying. “I have no idea what happened,” says she, holding up her 99 percent score. “I hardly even studied.” It’s a type you can never entirely escape, even in adulthood, as parents of school-age children quickly discover. “I don’t know what it is, but Daniel just scores off the charts on these standardized tests,” says Mom—dumbfounded!—at school pickup. “He certainly doesn’t get it from me.” No matter how much we prepare, no matter how early we rise, there’s always someone who does better with less, who magically comes alive at game time.

I’m not here to explain that kid. I don’t know of any study that looks at test taking as a discrete, stand-alone skill, or any evidence that it is an inborn gift, like perfect pitch. I don’t need research to tell me that this type exists; I’ve seen it too often with my own eyes. I’m also old enough to know that being jealous isn’t any way to close the gap between us and them. Neither is working harder. (Trust me, I’ve already tried that.)

No, the only way to develop any real test taking mojo is to understand more deeply what, exactly, testing

is

. The truth is not so self-evident, and it has more dimensions than you might guess.

The first thing to say about testing is this: Disasters happen. To everyone. Who hasn’t opened a test booklet and encountered a list of questions that seem related to a different course altogether? I have a favorite story about this, a story I always go back to in the wake of any collapse. The teenage Winston Churchill spent weeks preparing for the entrance exam into Harrow, the prestigious English boys school. He wanted badly to get in. On the big day, in March of 1888, he opened the exam and found, instead of history and geography, an unexpected emphasis on Latin and Greek. His mind went blank, he wrote later, and he was unable to answer a single question. “I wrote my name at the top of the page. I wrote down the number of the question, ‘1.’ After much reflection I put a bracket round it, thus, ‘(1).’ But thereafter I could not think of anything connected with it that was either relevant or true. Incidentally there arrived from nowhere in particular a blot and several smudges. I gazed for two whole hours at this sad spectacle; and then merciful ushers collected up my piece of foolscap and carried it up to the

Headmaster’s table.”