How to Live (5 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Montaigne had hitherto been keeping two lives going: one urban and political, the other rural and managerial. Although he had run the country estate since the death of his father in 1568, he had continued to work in Bordeaux. In early 1570, however, he put his magistracy up for sale. There were other reasons besides the accident: he had just been rejected for a post he had applied for in the court’s higher chamber, probably because political enemies had blocked him. It would have been more usual to appeal against this, or fight it; instead, he bailed out. Perhaps he did so in anger, or disillusionment. Or perhaps his own encounter with death, in combination

with the loss of his brother, made him think differently about how he wanted to live his life.

Montaigne had put in thirteen years of work at the Bordeaux

parlement

when he took this step. He was thirty-seven—middle-aged perhaps, by the standards of the time, but not old. Yet he thought of himself as retiring: leaving the mainstream of life in order to begin a new, reflective existence. When his thirty-eighth birthday came around, he marked the decision—almost a year after he had actually made it—by having a Latin inscription

painted on the wall of a side-chamber to his library:

In the year of Christ 1571, at the age of thirty-eight, on the last day of February, anniversary of his birth, Michel de Montaigne, long weary of the servitude of the court and of public employments, while still entire, retired to the bosom of the learned Virgins [the Muses], where in calm and freedom from all cares he will spend what little remains of his life now more than half run out. If the fates permit, he will complete this abode, this sweet ancestral retreat; and he has consecrated it to his freedom, tranquillity, and leisure.

From now on, Montaigne would live for himself rather than for duty. He may have underestimated the work involved in minding the estate, and he made no reference yet to writing essays. He spoke only of “calm and freedom.” Yet he had already completed several minor literary projects. Rather reluctantly, he had translated a theological work at his father’s request, and afterwards he had edited a sheaf of manuscripts left by his friend Étienne de La Boétie, adding dedications and a letter of his own describing La Boétie’s last days. During those few years around the turn of 1570, his dabblings in literature coexisted with other experiences: the series of bereavements and his own near-death, the desire to get out of Bordeaux politics, and the yearning for a peaceful life—and something else too, for his wife was now pregnant with their first child. The expectation of new life met the shadow of death; together they lured him into a new way of being.

Montaigne’s change of gear during his mid- to late thirties has been compared to the most famous life-changing crises in literature: those of Don Quixote, who abandoned his routine to set off in search of chivalric

adventure, and of Dante, who lost himself in the woods “midway on life’s path.”

Montaigne’s steps into his own midlife forest tangle, and his discovery of the path out of it, leave a series of footprints—the marks of a man faltering, stumbling, then walking on:

June 1568—Montaigne finishes his theological translation. His father dies; he inherits the estate

Spring 1569—His brother dies in the tennis accident

1569—His career stalls in Bordeaux

1569 or early 1570—He almost dies

Autumn 1569—His wife becomes pregnant

Early 1570—He decides to retire

Summer 1570—He retires

June 1570—His first baby is born

August 1570—His first baby dies

1570—He edits La Boétie’s works

February 1571—He makes his birthday inscription on the library wall

1572—He starts writing the

Essays

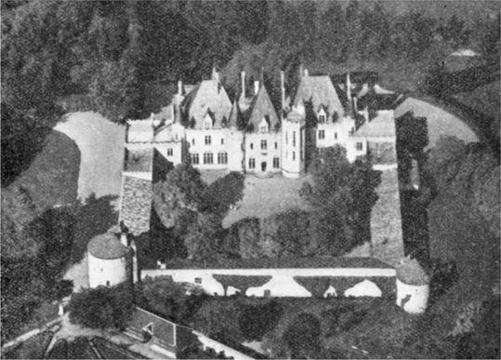

Having committed himself to what he hoped would be a contemplative new life, Montaigne went to great trouble to set it up just as he wanted it. After his retirement, he chose one of two towers at the corners of his château complex to be his all-purpose retreat and center of operations; the other tower was reserved for his wife. Together with the main château building and the linking walls, these two corner-pieces enclosed a simple, square courtyard, set amid fields and forests.

The main building has gone now. It burned down in 1885, and was replaced by a new building to the same design. But, by good fortune, the fire did not touch Montaigne’s tower; it remains essentially unchanged, and can still be visited. Walking around, it is not hard to see why he liked it so much. From the outside, it looks endearingly chubby for a four-story tower, having walls as thick as a sandcastle’s. It was originally designed to be used for defense; Montaigne’s father adapted it for more peaceful uses. He turned the ground floor into a chapel, and added an inner spiral staircase. The floor above the chapel became Montaigne’s bedroom. He often slept there rather than returning to the main building.

Set off the steps above this room was a niche for a toilet. Above that—just below the attic, with its

“very big bell” which rang out hours deafeningly—was Montaigne’s favorite haunt: his library.

Climbing up the steps today—their stone worn into hollows by many feet—one can enter this library and walk around it in a tight circle, looking out of the windows over the courtyard and landscape just as Montaigne would have done. The view would not have been that different in his time, but the room itself would. Now stark and white, with bare stone floors, it would then have had a covering underfoot, probably of rushes. On its walls were murals, still fresh. In winter, fires would have burned in most of the rooms, though not in the main library, which had no fireplace. Cold days sent Montaigne to the cosier side-chamber next door, since that did have a fire.

The most striking feature of the main library room, when Montaigne occupied it, was his fine collection of books, housed in five rows on a beautiful curving set of shelves.

The curve was necessary to fit the round tower, and must have been quite a carpentry challenge. The shelves presented all Montaigne’s books to his view at a single glance: a satisfying sweep. He owned around a thousand volumes by the time he moved into

the library, many inherited from his friend La Boétie, others bought by himself. It was a substantial collection, and Montaigne actually read his books, too. Today they are dispersed; the shelves too have gone.

Also around the room were Montaigne’s other collections: historical memorabilia, family heirlooms, artifacts from South America. Of his ancestors, he wrote, “I keep their handwriting, their seal, the breviary, and a peculiar sword that they used, and I have not banished from my study some long sticks that my father ordinarily carried in his hand.”

The South American collection was built up from travelers’ gifts; it included jewelry, wooden swords, and ceremonial canes used in dancing. Montaigne’s library was not just a repository or a work space. It was a chamber of marvels, and sounds like a sixteenth-century version of Sigmund Freud’s last home in London’s Hampstead: a treasure-house stuffed with books, papers, statuettes, pictures, vases, amulets, and ethnographic curiosities, designed to stimulate both imagination and intellect.

The library also marked Montaigne out as a man of fashion. The trend for such retreats had been spreading slowly through France, having begun in Italy in the previous century.

Well-off men filled chambers with books and reading-stands, then used them as a place to escape to on the pretext of having to work. Montaigne took the escape factor further by removing his library from the house altogether. It was both a vantage point and a cave, or, to use a phrase he himself liked, an

arrière-boutique:

a “room behind the shop.” He could invite visitors there if he wished—and often did—but he was never obliged to. He loved it. “Sorry the man, to my mind, who has not in his own home a place to be all by himself, to pay his court privately to himself, to hide!”

Since the library represented freedom itself, it is not surprising that Montaigne made a ritual of decorating it and setting it apart. In the side-chamber, along with the inscription celebrating his retirement, he had floor-to-ceiling murals painted.

These have faded, but, from what remains visible, they depicted great battles, Venus mourning the death of Adonis, a bearded Neptune, ships in a storm, and scenes of bucolic life—all evocations of the classical world. In the main chamber, he had the roof beams painted with quotations, also mostly classical. This, too, was a fashion, though it remained a minority taste. The Italian humanist Marsilio Ficino put

quotations on the walls of his villa in Tuscany, and later, in the Bordeaux area, the baron de Montesquieu would do the same in deliberate homage to Montaigne.

Over the years, Montaigne’s roof beams faded too, but they were later restored to clear legibility, so that, as you walk around the room now, voices whisper from above your head:

Solum certum nihil esse certi

Et homine nihil miserius aut superbius

Only one thing is certain: that nothing is certain

And nothing is more wretched or arrogant than man. (Pliny the Elder)

How can you think yourself a great man, when the first accident that comes along can wipe you out completely? (Euripides)

There is no more beautiful life than that of a carefree man; Lack of care is a truly painless evil. (Sophocles)

The beams form a vivid reminder of Montaigne’s decision to move from public life into a meditative existence—a life to be lived, literally, under the sign of philosophy rather than that of politics. Such a shift of realms was also part of the ancients’ advice. The great Stoic Seneca repeatedly urged his fellow Romans to retire in order to “find themselves,” as we might put it.

In the Renaissance, as in ancient Rome, it was part of the well-managed life. You had your period of civic business, then you withdrew to discover what life was really about and to begin the long process of preparing for death. Montaigne developed reservations about the second part of this, but there is no doubt about his interest in contemplating life. He wrote: “Let us cut loose from all the ties that bind us to others; let us win from ourselves the power to live really alone and to live that way at our ease.”