How to Live (3 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

This book is about Montaigne, the man and writer. It is also about Montaigne, the long party—that accumulation of shared and private conversations over four hundred and thirty years. The ride will be a strange and bumpy one, for Montaigne’s book has not slid smoothly through time

like a pebble in a stream, becoming ever more streamlined and polished as it goes. It has tumbled about in no set direction, picking up debris, sometimes snagging on awkward outcrops. My story rolls with the current too. It goes “befuddled and staggering,” with frequent changes of tack. At first, it sticks more closely to the man himself: Montaigne’s life, personality, and literary career. Later, it diverges ever further into tales of his book and his readers, all the way up to very recent ones. Since it is a twenty-first-century book, it is inevitably pervaded by a twenty-first-century Montaigne. As one of his favorite adages had it, there is no escaping our perspective: we can walk only on our own legs, and sit only on our own bum.

Most of those who come to the

Essays

want something from it. They may be seeking entertainment, or enlightenment, or historical understanding, or something more personal. As the novelist Gustave Flaubert

advised a friend who was wondering how to approach Montaigne:

Don’t read him as children do, for amusement, nor as the ambitious do, to be instructed. No, read him

in order to live

.

Impressed by Flaubert’s command, I am taking the Renaissance question “How to live?” as a guide-rope for finding a way through the tangle of Montaigne’s life and afterlife. The question remains the same throughout, but the chapters take the form of twenty different answers—each an answer that Montaigne might be imagined as having given. In reality, he usually responded to questions with flurries of further questions and a profusion of anecdotes, often all pointing in different directions and leading to contradictory conclusions. The questions and stories

were

his answers, or further ways of trying the question out.

Similarly, each of the twenty possible answers in this book will take the form of something anecdotal: an episode or theme from Montaigne’s life, or from the lives of his readers. There will be no neat solutions, but these twenty “essays” at an answer will allow us to eavesdrop on snippets of the long conversation, and to enjoy the company of Montaigne himself—most genial of interlocutors and hosts.

HANGING BY THE TIP OF HIS LIPS

M

ONTAIGNE WAS NOT

always a natural at social gatherings. From time to time, in youth, while his friends were dancing, laughing, and drinking, he would sit apart under a cloud. His companions barely recognized him on these occasions; they were more used to seeing him flirting with women, or animatedly debating a new idea that had struck him. They would wonder whether he had taken offense at something they had said. In truth, as he confided later in his

Essays

, when he was in this mood he was barely aware of his surroundings at all. Amid the festivities, he was thinking about some frightening true tale he had recently heard—perhaps one about a young man who, having left a similar feast a few days earlier complaining of a touch of mild fever, had died of that fever almost

before his fellow party-goers had got over their hangovers.

If death could play such tricks, then only the flimsiest membrane separated Montaigne himself from the void at every moment. He became so afraid of losing his life that he could no longer enjoy it while he had it.

In his twenties, Montaigne suffered this morbid obsession because he had spent too much time reading classical philosophers. Death was a topic of which the ancients never tired. Cicero summed up their principle neatly: “To philosophize is to learn how to die.”

Montaigne himself would one day borrow this dire thought for a chapter title.

But if his problems began with a surfeit of philosophy at an impressionable age, they did not end just because he grew up. As he reached his thirties, when he might have been expected to gain a more measured perspective, Montaigne’s sense of the oppressive proximity of death became stronger than ever, and more personal. Death turned from an abstraction into a reality, and began scything its way through almost everyone he cared about, getting closer to himself. When he was thirty, in 1563, his best friend Étienne de La Boétie was killed by the plague. In 1568, his father died, probably of complications following a kidney-stone attack. In the spring of the following year, Montaigne lost his younger brother Arnaud de Saint-Martin to a freak sporting accident. He himself had just got married then; the first baby of this marriage would live to the age of two months, dying in August 1570. Montaigne went on to lose four more children: of six, only one survived to become an adult. This series of bereavements made death less nebulous as a threat, but it was hardly reassuring. His fears were as strong as ever.

The most painful loss was apparently that of La Boétie; Montaigne loved him more than anyone. But the most shocking must have been that of his brother Arnaud. At just twenty-seven, Arnaud was struck on the head by a ball while playing the contemporary version of tennis, the

jeu de paume

. It cannot have been a very forceful blow, and he showed no immediate effect, but five or six hours later he lost consciousness and died, presumably from a clot or hemorrhage. No one would have expected a simple knock on the head to cut off the life of a healthy man. It made no sense, and was even more personally threatening than the story of the young man who had died of fever. “With such frequent and ordinary examples passing before our

eyes,” wrote Montaigne of Arnaud, “how can we possibly rid ourselves of the thought of death and of the idea that at every moment it is gripping us by the throat?”

Rid himself of this thought he could not; nor did he even want to. He was still under the sway of his philosophers. “Let us have nothing on our minds as often as death,” he wrote in an early essay on the subject:

At every moment let us picture it in our imagination in all its aspects. At the stumbling of a horse, the fall of a tile, the slightest pin prick let us promptly chew on this: Well, what if it were death itself?

If you ran through the images of your death often enough, said his favorite sages, the Stoics, it could never catch you by surprise. Knowing how well prepared you were, you should be freed to live without fear. But Montaigne found the opposite. The more intensely he imagined the accidents that might befall him and his friends, the less calm he felt. Even if he managed, fleetingly, to accept the idea in the abstract, he could never accommodate it in detail. His mind filled with visions of injuries and fevers; or of people weeping at his deathbed, and perhaps the “touch of a well-known hand” laid on his brow to bid him farewell.

He imagined the world closing around the hole where he had been: his possessions being gathered up, and his clothes distributed among friends and servants. These thoughts did not free him; they imprisoned him.

Fortunately, this constriction did not last. By his forties and fifties, Montaigne was liberated into light-heartedness. He was able to write the most fluid and life-loving of his essays, and he showed almost no remaining sign of his earlier morbid state of mind. We only know that it ever existed because his book tells us about it. He now refused to worry about anything. Death is only a few bad moments at the end of life, he wrote in one of his last added notes; it is not worth wasting any anxiety over.

From being the gloomiest among his acquaintances, he became the most carefree of middle-aged men, and a master of the art of living well. The cure lay in a journey to the heart of the problem: a dramatic encounter with his own death, followed by an extended midlife crisis which led him to the writing of his

Essays

.

The great meeting between Montaigne and death happened on a day some time in 1569 or early 1570—the exact period is uncertain—when he was out doing one of the things that usually dissipated his anxieties and gave him a feeling of escape: riding his horse.

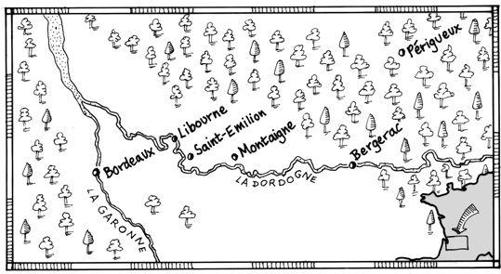

He was about thirty-six at this time, and felt he had a lot to escape from. Following his father’s death, he had inherited full responsibility for the family château and estate in the Dordogne. It was beautiful land, in an area covered, then as now, by vineyards, soft hills, villages, and tracts of forest. But for Montaigne it represented the burden of duty. On the estate, someone was always plucking at his sleeve, wanting something or finding fault with things he had done. He was the

seigneur:

everything came back to him.

Fortunately, it was not usually difficult to find an excuse to be somewhere else. As he had done since he was twenty-four, Montaigne worked as a magistrate in Bordeaux, the regional capital some thirty miles away—so there were always reasons to go there. Then there were the far-flung vineyards of the Montaigne property itself, scattered in separate parcels around the countryside for miles, and useful for visits if he felt so inclined.

He also made occasional calls on the neighbors who lived in other châteaus of the area; it was important to stay on good terms. All these tasks formed excellent justifications for a ride through the woods on a sunny day.

Out on the forest paths, Montaigne’s thoughts could wander as widely as he wished, although even here he was invariably accompanied by servants and acquaintances.

People rarely went around alone in the sixteenth century. But he could spur his horse away from boring conversations, or turn his mind aside in order to daydream, watching the light glinting in the canopy of trees over the forest path. Was it really true, he might wonder, that a man’s semen came from the marrow of the spinal column, as Plato said? Could a remora fish really be so strong that it could hold back a whole ship just by fastening its lips on it and sucking? And what about the strange incident he had seen at home the other day, when his cat gazed intently into a tree until a bird fell out of it, dead, right between her paws? What power did she have? Such speculations were so absorbing that Montaigne sometimes forgot to pay full attention to the path and to what his companions were doing.