How to Live (22 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

The result, in any case, was that he lived his life without ever encountering serious problems with the Church: quite an achievement for a man who wrote so freely, who lived on a border between Catholic and Protestant lands, and who occupied public office in a time of religious war. When he was traveling in Italy in the 1580s, Inquisition officials did inspect the

Essays

and produced a list of mild objections.

One was that he used the word

Fortune

instead of the officially approved

Providence

. (Providence comes from God and allows room for free will; Fortune is just the way the cookie crumbles.) Others were that he quoted heretical poets, that he made excuses for the apostate emperor Julian, that he thought anything beyond simple execution cruel, and that he recommended bringing children up naturally and freely. But the Inquisition did not mind his views on death, his reservations about witchcraft trials, or—least of all—his Skepticism.

It was, in fact, the

Essays’

Skepticism that made it such a success on first publication, alongside its Stoicism and Epicureanism. It managed to appeal to thoughtful, independent-minded readers, but also to the most orthodox

of churchmen. It pleased people like Montaigne’s Bordeaux colleague Florimond de Raemond, a zealous Catholic whose favorite subject, in his own writings, was the imminent arrival of the Antichrist and the coming Apocalypse. Raemond advised people to read Montaigne to fortify themselves against heresy, and particularly praised the “beautiful Apology” because of its abundance of stories demonstrating how little we know about the world.

He borrowed several such stories for a chapter of his own work

L’Antichrist

, entitled “Strange things of which we do not know the reason.” Why does an angry elephant become calm on seeing a sheep? he asked. Why does a wild bull become docile if he is tethered to a fig tree? And how exactly does the remora fish apply its little hooks to a ship’s hull to hold it back at sea? Raemond sounds so amiable and shows such a bright amazement about natural wonders that one has to pinch oneself to remember that he believed the end of the world was nigh. Fideism produced odd bedfellows indeed; extremists and secular moderates were brought together by a shared desire to marvel at their own ignorance.

Thus, the early Montaigne was embraced by the orthodox as a pious Skeptical sage, a new Pyrrho as well as a new Seneca: the author of a book at once consoling and morally improving. It comes as a surprise, therefore, to discover that by the end of the following century he was shunned with horror and that the

Essays

was consigned to the

Index of Prohibited Books

, there to stay for almost a hundred and eighty years.

The problem began with discussion of a topic which one might think of little importance: animals.

Montaigne’s favorite trick for undermining human vanity was the telling of animal stories like those that so intrigued Florimond de Raemond—many of them liberated from Plutarch. He liked them because they were entertaining, yet had a serious purpose. Tales of animal cleverness and sensitivity demonstrated that human abilities were far from exceptional, and indeed that animals do many things better than we do.

Animals can be good, for example, at working cooperatively. Oxen, hogs,

and other creatures will gather in groups for self-defense. If a parrotfish is hooked by a fisherman, his fellow parrotfish rush to chew through the line and free him.

Or, if one is netted, others thrust their tails through the net so he can grab one with his teeth, and be pulled out. Even different species can work together in this way, as with the pilot fish that guides the whale, or the bird that picks the crocodile’s teeth.

Tuna fish demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of astronomy: when the winter solstice arrives, the whole school stops precisely where it is in the water, and stays there until the following spring equinox. They know geometry and arithmetic too, for they have been observed to form themselves into a perfect cube of which all six sides are equal.

Morally, animals prove themselves at least as noble as humans. For repentance, who can surpass the elephant who was so grief-stricken about having killed his keeper in a fit of temper that he deliberately starved himself to death? And what of the female halcyon, or kingfisher, who loyally carries a wounded mate around on her shoulders, for the rest of her life if need be? These loving kingfishers also show a flair for technology: they use fishbones to build a structure that acts as both nest and boat, cleverly testing it for leaks near a shore first before launching it into open sea.

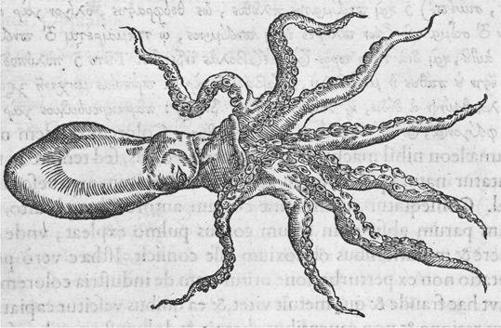

Animals surpass us in miscellaneous abilities of all kinds. Humans change color, but in an uncontrolled way: we blush when we are embarrassed, and go pale when we are frightened. This places us on the same level as chameleons, who also change at the mercy of chance conditions, but far below the octopus, who can blend his colors however and whenever he pleases. We and the chameleons can only gaze up in admiration at the mighty octopus—a shock for human vanity.

Yet still we humans persist in thinking of ourselves as separate from all other creatures, closer to gods than to chameleons or parrotfish. It never occurs to us to rank ourselves among animals, or to put ourselves in their minds. We barely stop to wonder whether they have minds at all. Yet, for Montaigne, it is enough to watch a dog dreaming to see that it must have an inner world just like ours. A person who dreams about Rome or Paris conjures up an insubstantial Rome or Paris within. Likewise, a dog dreaming about a hare surely sees a disembodied hare running through his dream. We sense this from the twitching of his paws as he runs after it: a hare is there for him somewhere, albeit “a hare without fur or bones.”

Animals populate their internal world with ghosts of their own invention, just as we do.

Montaigne’s animal stories seemed both delightful and innocuous to his first readers. If anything, they were morally useful, pointing out that humans are modest beings who cannot expect to master or understand much on God’s earth. But as the sixteenth century receded into history and the seventeenth rolled on, people became increasingly disturbed by this picture of themselves as less refined or capable than an octopus. It seemed degrading rather than merely humbling. By the 1660s, the “Apology,” where most of the animal stories are found, no longer looked like a treasure chest of uplifting wisdom. It looked like a case study in everything that had gone wrong with the morals of the previous century. Montaigne’s easy acceptance of human fallibility and of our animalistic side was now something to be fought against—almost a trick of the Devil himself.

Typical of the new attitude was a denunciation from the pulpit by the bishop Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet in 1668.

Montaigne, he said,

prefers animals to men, their instinct to our reason, their simple, innocent, and plain nature … to our refinements and malices. But tell

me, subtle philosopher, who laughs so cleverly at man for imagining himself to be something [more than an animal], do you reckon it as nothing to know God?

The challenging tone was new, and so was the feeling that human dignity needed defending against a “subtle” enemy. The seventeenth century would cease to accept Montaigne as a sage; it would begin to see him as a trickster and a subversive. Montaigne’s animal stories and his debunking of human pretensions would prove particularly irksome to two of the greatest writers of the new era: René Descartes and Blaise Pascal.

They had no sympathy for each other; this makes it all the more noteworthy that they came together in disapproval of Montaigne.

René Descartes, the greatest philosopher of the early modern era, was interested in animals mainly as a contrast to human beings. Humans have a conscious, immaterial mind; they can reflect on their own experience, and say “I think.” Animals cannot. For Descartes, they therefore lack souls and are no more than machines. They are programmed to walk, run, sleep, yawn, sneeze, hunt, roar, scratch themselves, build nests, raise young, eat, and defecate, but they do this in the same way as a clockwork automaton might whirr its gears and trundle across the floor. A dog, for Descartes, has no perspective, no true experience. It does not create a hare in its inner world and chase it across the fields. It can snuffle and twitch its paws all it likes; Descartes will never see anything but contracting muscles and firing nerves, triggered by equally mechanical operations in the brain.

Descartes cannot truly exchange a glance with an animal. Montaigne can, and does. In one famous passage, he mused: “When I play with my cat, who knows if I am not a pastime to her more than she is to me?”

And he added in another version of the text: “We entertain each other with reciprocal monkey tricks. If I have my time to begin or to refuse, so has she hers.” He borrows his cat’s point of view in relation to him just as readily as he occupies his own in relation to her.

Montaigne’s little interaction with his cat is one of the most charming moments in the

Essays

, and an important one too. It captures his belief that all beings share a common world, but that each creature has its own way of perceiving this world. “All of Montaigne lies in that casual sentence,” one

critic has commented.

Montaigne’s cat is so celebrated that she has inspired a full scholarly article, and an entry to herself in Philippe Desan’s

Dictionnaire de Montaigne

.

All Montaigne’s skills at jumping between perspectives come to the fore when he writes about animals. We find it hard to understand them, he says, but they must find it just as hard to understand us. “This defect that hinders communication between them and us, why is it not just as much ours as theirs?”

We have some mediocre understanding of their meaning; so do they of ours, in about the same degree. They flatter us, threaten us, and implore us, and we them.

Montaigne cannot look at his cat without seeing her looking back at him, and imagining himself as he looks to her. This is the kind of interaction between flawed, mutually aware individuals of different species that can never happen for Descartes, who was disturbed by it, as were others in his century.

In Descartes’s case, the problem was that his whole philosophical structure required a point of absolute certainty, which he found in the notion of a clear, undiluted consciousness. There could be no room in this for Montaigne’s boundary-blurring ambiguities: his reflections on a deranged or rabid Socrates or on the superior senses of a dog. The complications which gave Montaigne pleasure alarmed Descartes. Yet, ironically, his desire for such a point of pure certainty had arisen largely in response to his understanding of Pyrrhonian doubt, as transmitted primarily by Montaigne—leading Pyrrhonian of the modern world.

Descartes’s solution came to him in November 1619 when, after a period of traveling and observing the diversity of human customs, he shut himself up in a German room heated by a wood stove and devoted one whole uninterrupted day to thinking. He started with the Skeptical assumption that nothing was real, and that all his previous beliefs had been false. Then he advanced slowly, with careful steps, “like a man who walks alone, and in the dark,” replacing these false beliefs with logically justified ones. It was a purely mental progress; as he moved from step to step, his body remained by the fire, where one imagines him staring into the embers for hours. The image of Descartes in front of his stove, perhaps in the hunched position of Rodin’s

Thinker

, provides a neat contrast to the image of Montaigne pacing up and down, pulling books off the shelves, getting distracted, mentioning odd thoughts to his servants to help himself remember them, and arriving at his best ideas in heated dinner-party discussions with neighbors or while riding in the woods. Even in “retirement,” Montaigne did his thinking in a richly populated environment, full of objects, books, animals, and people. Descartes needed motionless withdrawal.