How to Live (11 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Crowds of rebels assembled to protest, and for five days from August 17 to August 22, 1548, mobs roamed the streets setting fire to tax collectors’ houses. Some attacked the homes of anyone who looked rich, until the disorder threatened to turn into a general peasant uprising. A few tax collectors were killed. Their bodies were dragged through the streets and covered in heaps of salt to underline the point. In one of the worst incidents, Tristan de Moneins, the town’s lieutenant-general and governor—thus the king’s official representative—was lynched.

He had shut himself up in the city’s massive royal citadel, the Château Trompette, but a crowd gathered outside and howled for him to come out. Perhaps thinking to earn their respect by facing up to them, he ventured forth, but it was a mistake. They beat him to death.

Then fifteen, Montaigne was out in the streets, for the Collège had suspended classes during the violence. He witnessed the killing of Moneins, a scene he never forgot. It raised in his mind, perhaps for the first time, a question that would haunt the entire

Essays

in varying guises: whether it was better to win an enemy’s respect by an open display of defiance, or to throw yourself on his mercy and hope to win him over by submission or an appeal to his better self.

In this case, Montaigne thought Moneins had failed because he was not sure what he was trying to do. Having decided to brave the crowd, he then lost his confidence and behaved with deference, sending mixed messages. He also underestimated the distorted psychology of a mob. Once worked up into a frenzy, it can only be either soothed or suppressed; it cannot be expected to show ordinary human sympathy. Moneins seemed not to know this. He expected the same fellow-feeling as he would from an individual.

He was certainly brave to cast himself unarmed into a “sea of madmen.” But his only hope then would have been to maintain this bold face to the end. He

should have swallowed the whole cup and not abandoned his role; whereas what happened to him was that after having seen the danger close up, he lost his nerve and changed once again that deflated and fawning countenance that he had assumed into a frightened one, filling his voice and his eyes with astonishment and penitence. Trying to hole up and hide, he inflamed them and called them down on himself.

The shocking sight of Moneins’s murder, and no doubt of other disturbing scenes during that week, taught Montaigne a great deal about the psychological complexity of conflict and the difficulty of conducting oneself well in crises. In this case, the violence was eventually calmed, mainly by Montaigne’s future father-in-law, Geoffrey de La Chassaigne, who negotiated a truce. But the city would suffer a severe punishment for allowing such disobedience. Ten thousand royal troops were sent there in October under the Constable de Montmorency; the title “constable” officially meant only “chief of the royal stables,” but his job was one of immense power.

The troops remained for over three months, with Montmorency conducting a reign of terror. He encouraged his men to loot and kill like an occupying force in a foreign country. Anyone directly identified as having taken part in the riots was broken on the wheel, or burned. Everything was done to humiliate Bordeaux physically, financially, and morally. It lost legal jurisdiction over its own affairs; its artillery and gunpowder were confiscated; its

parlement

was dissolved, and for a while it was governed by magistrates from other parts of France. It also had to pay the costs of its own occupation. And, when Moneins’s body was exhumed for reburial in the cathedral, local officials were obliged to fall on their knees in front of Montmorency’s house to beg forgiveness for the killing.

The privileges were gradually restored, thanks in part to Montaigne’s father’s efforts, as mayor, to make Bordeaux look good again in the king’s eyes. Amazingly, in the long run, the rebellion did achieve its aim. Unnerved by the riots, Henri II decided not to enforce the salt tax. But the price had been high.

Just as this drama subsided, in 1549, plague broke out in the city. It was not a long or major outbreak, but it was enough to make everyone examine their skin uneasily and dread the sound of a cough. It also forced the Collège to close again for a while—but by this time Montaigne had probably already moved on. He left the school some time around 1548, ready to start the next phase of his young life.

There now follows a long period, until 1557, in which it is not clear what he was doing. He may have returned to the estate. He may have been sent to an academy, a sort of finishing school where young men learned the noble accomplishments of riding, dueling, hunting, heraldry, singing, and dancing. (If so, Montaigne paid no attention to anything except the riding lessons: this was the only one of these skills he later claimed to be good at.) At some stage, he must also have studied the law. He emerged into adulthood with all he needed to become a successful young

seigneur

, and, despite his dislike of the experience, with a useful set of abilities and experiences acquired from school. Foremost among these was a discovery that would have delighted his father: that of books, and of the worlds they opened up to him—worlds far beyond the vineyards of Guyenne and the tedium of a sixteenth-century schoolhouse.

Q. How to live? A. Read a lot, forget most of what you read, and be slow-witted

READING

T

HE CLOSE GRAMMATICAL

study of Cicero and Horace almost killed Montaigne’s interest in literature before it was born.

But some of the teachers at the school helped keep it going, mainly by not taking more entertaining books out of the boy’s hands when they caught him reading them, and perhaps even by slipping a few more his way—doing this so discreetly that he could enjoy reading them without ceasing to feel like a rebel.

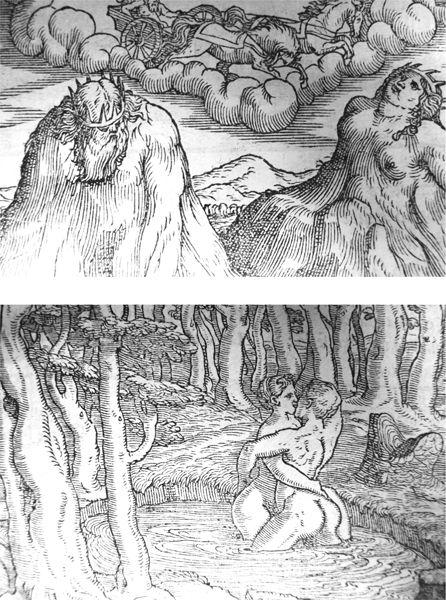

One unsuitable text which Montaigne discovered for himself at the age of seven or eight, and which changed his life, was Ovid’s

Metamorphoses

. This tumbling cornucopia of stories about miraculous transformations among ancient gods and mortals was the closest thing the Renaissance had to a compendium of fairy tales. As full of horrors and delights as a Grimm or Andersen, and quite unlike the texts of the schoolroom, it was the sort of thing an imaginative sixteenth-century boy could read with eyes rounded and fingers white-knuckled from gripping the covers too tightly.

In Ovid, people change. They turn into trees, animals, stars, bodies of water, or disembodied voices. They alter sex; they become werewolves. A woman called Scylla enters a poisonous pool and sees each of her limbs turn into a dog-like monster from which she cannot pull away because the monsters are also

her

. The hunter Actaeon is changed into a stag, and his own hunting-dogs chase him down. Icarus flies so high that the sun burns him. A king and a queen turn into two mountains. The nymph Samacis plunges herself into the pool where the beautiful Hermaphroditus is bathing, and wraps herself around him like a squid holding fast to its prey, until her flesh melts into his and the two become one person, half male, half female. Once a taste of this sort of thing had started him off, Montaigne galloped through other books similarly full of good stories: Virgil’s

Aeneid

, then Terence, Plautus, and various modern Italian comedies. He learned, in

defiance of school policy, to associate reading with excitement. It was the one positive thing to come out of his time there. (“But,” Montaigne adds, “for all that, it was still school.”)

Many of his early discoveries remained lifelong loves. Although the initial thrill of the

Metamorphoses

wore off, he filled the

Essays

with stories from it, and emulated Ovid’s style of slipping from one topic to the next without introduction or apparent order.

Virgil continued to be a favorite too, though the mature Montaigne was cheeky enough to suggest that some passages in the

Aeneid

might have been “brushed up a little.”

Because he liked to know what people really did, rather than what someone imagined they might do, Montaigne’s preference soon shifted from poets to historians and biographers. It was in real-life stories, he said, that you encountered human nature in all its complexity. You learned the “diversity and truth” of man, as well as “the variety of the ways he is put together, and the accidents that threaten him.”

Among historians, he liked Tacitus best, once remarking that he had just read through his

History

from beginning to end without interruption. He loved how Tacitus treated public events from the point of view of “private behavior and inclinations,” and was struck by the historian’s fortune in living through a “strange and extreme” period, just as Montaigne himself did. Indeed, he wrote of Tacitus, “you would often say that it is us he is describing.”

Turning to biographers, Montaigne liked those who went beyond the external events of a life and tried to reconstruct a person’s inner world from the evidence. No one excelled in this more than his favorite writer of all: the Greek biographer Plutarch, who lived from around

AD

46 to around 120 and whose vast

Lives

presented narratives of notable Greeks and Romans in themed pairs. Plutarch was to Montaigne what Montaigne was to many later readers: a model to follow, and a treasure chest of ideas, quotations, and anecdotes to plunder. “He is so universal and so full that on all occasions, and however eccentric the subject you have taken up, he makes his way into your work.” The truth of this last part is undeniable: several sections of the

Essays

are paste-ins from Plutarch, left almost unchanged. No one thought of this as plagiarism: such imitation of great authors was then considered an excellent practice. Moreover, Montaigne subtly changed everything he stole, if only by setting it in a different context and hedging it around with uncertainties.

He loved the way Plutarch assembled his work by stuffing in fistfuls of images, conversations, people, animals, and objects of all kinds, rather than

by coldly arranging abstractions and arguments. His writing is full of

things

, Montaigne pointed out. If Plutarch wants to tell us that the trick in living well is to make the best of any situation, he does it by telling the story of a man who threw a stone at his dog, missed, hit his stepmother instead, and exclaimed, “Not so bad after all!” Or, if he wants to show us how we tend to forget the good things in life and obsess only about the bad, he writes about flies landing on mirrors and sliding about on the smooth surface, unable to find a footing until they hit a rough area. Plutarch leaves no neat endings, but he sows seeds from which whole worlds of inquiry can be developed. He points where we can go if we like; he does not lead us, and it is up to us whether we obey or not.

Montaigne also loved the strong sense of Plutarch’s own personality that comes across in his work: “I think I know him even into his soul.” This was what Montaigne looked for in a book, just as people later looked for it in him: the feeling of meeting a real person across the centuries. Reading Plutarch, he lost awareness of the gap in time that divided them—much bigger than the gap between Montaigne and us. It does not matter, he wrote, whether a person one loves has been dead for fifteen hundred years or, like his own father at the time, eighteen years. Both are equally remote; both are equally close.

Montaigne’s merging of favorite authors with his own father says a lot about how he read: he took up books as if they were people, and welcomed them into his family.

The rebellious, Ovid-reading boy would one day accumulate a library of around a thousand volumes: a good size, but not an indiscriminate assemblage. Some were inherited from his friend La Boétie; others he bought himself. He collected unsystematically, without adding fine bindings or considering rarity value. Montaigne would never repeat his father’s mistake of fetishizing books or their authors. One cannot imagine him kissing volumes like holy relics, as Erasmus or the poet Petrarch reportedly used to, or putting on his best clothes before reading them, like Machiavelli, who wrote: “I strip off my muddy, sweaty, workaday clothes, and put on the robes of court and palace, and in this graver dress I enter the courts of the ancients and am welcomed by them.”

Montaigne would have found this ridiculous. He preferred to converse with the ancients in a tone of camaraderie,

sometimes even teasing them, as when he twits Cicero for his pomposity or suggests that Virgil could have made more of an effort.

Effort was just what he himself claimed never to make, either in reading or writing. “I leaf through now one book, now another,” he wrote, “without order and without plan, by disconnected fragments.”

He could sound positively cross if he thought anyone might suspect him of careful scholarship. Once, catching himself having said that books offer consolation, he hastily added, “Actually I use them scarcely any more than those who do not know them at all.” And one of his sentences starts, “We who have little contact with books …” His rule in reading remained the one he had learned from Ovid: pursue pleasure. “If I encounter difficulties in reading,” he wrote, “I do not gnaw my nails over them; I leave them there. I do nothing without gaiety.”