How (39 page)

Authors: Dov Seidman

DOING CULTURE

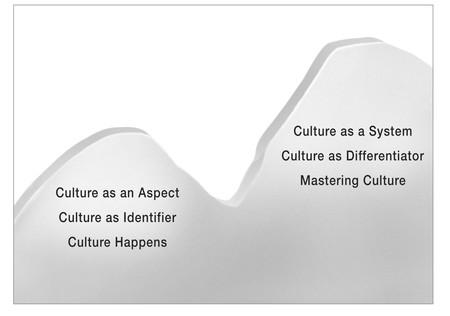

In this chapter, we’ve broken culture down into its constituent parts and developed a vocabulary with which to understand the way groups in an enterprise function. These various dimensions of culture combine in myriad and infinite ways to create unique and diverse group cultures, as impossible to replicate as a snowflake. This tremendous variety means culture can become a key source of long-term differentiation.

We’ve also taken the first steps toward an understanding of both the importance of culture to our ability to thrive and the fact that culture is something we do, and can do, in an active way. Culture is made of the little things that pass between people every day. Taken as a whole, these HOWs form an organic ecosystem that can be planted, watered, fertilized, weeded, and given plenty of encouragement to grow. Grasping how culture works gives you the building blocks to grow a culture that can really outbehave the competition.

In the next chapter, we chart a path forward toward a new model for group culture that can best equip us for the road ahead: values-based self-governance.

CHAPTER

11

The Case for Self-Governing Cultures

If from lawlessness or fickleness, from folly

or self-indulgence, [we] refuse to govern

[our]selves, then assuredly in the end [we]

will have to be governed from the outside.

—Theodore Roosevelt, 1907

C

ulture lies in the synapses between individual units of a system, whether that be neurons in the brain, individuals in a group, or units in a conglomerate. Now that we understand something about the general types of culture at work in most business endeavors today, and the various dimensions that define and influence how these cultures function, what do we do with that knowledge? How does it help us make Waves, go on TRIPs, and continue to thrive in the new conditions of twenty-first-century business?

Blind obedience, informed acquiescence, and values-based self-governance are not just types of culture; they also describe an approach to governing—how organizations create the rules, structures, policies, and procedures that shape the way people behave and perform. As we discussed, blind obedience and informed acquiescence cultures place most governance outside the individual, in the hands of a boss or a set of rules. They seek to control things the same way the guardrails in a bowling alley are used to keep kids’ balls from rolling into the gutter; roll the ball and the guardrails keep it on the lane and moving in the right direction. Transparency and connectedness, however, make cultures based on one form of external control or another less ideal for our new world. It is no longer enough to just get the ball to the pins; because everyone is watching, we must now bowl strikes. Few would deny that in a horizontal, hyperconnected, and hypertransparent world, to bowl strikes we need a working environment that connects people and groups more intensely, is powered by communication and information flow, and enfranchises individuals at all levels of the company to act quickly and autonomously when presented with new opportunities by the fast-moving marketplace.

But as the rapid changes in technology since the mid-1990s created a new type of hyperconnected worker, little has changed in the underlying structures of how we organize and govern ourselves to truly take advantage of our new reality. The guardrails are still in place. To thrive in the new conditions of twenty-first-century capitalism, groups must learn to place the structures of governance in each individual’s hands. At the heart of this process lies a fundamentally different relationship between governance—the way we seek to control things—and culture—the way things really happen. Instead of achieving culture through governance, companies must learn to govern

through

culture, to put the guardrails of governance within the culture itself.

To govern through culture is to govern through HOWs, through the internal structures that influence every action and relationship in an organization. This represents a profound shift in focus from blind obedience and informed acquiescence, the two governing systems with which we are most familiar. It moves governance higher up the food chain, if you will, while also distributing it throughout the diverse parts of the variegated whole. Rather than governing with a matrix of rules and authorities laid over the organization, governing through culture is about governing from within the corpus. When governing through culture, rules don’t work well, values do; motivation does not bind people together, beliefs will; external controls are less effective, and self-governance is more efficient. A culture of HOW, one that uniquely transforms new conditions into new opportunities, as we have already learned, has a name: values-based self-governance.

SELF-GOVERNANCE ON THE SHOP FLOOR

We have three compelling reasons to embrace the idea of governing through culture: We can, we must, and we should do so.

We Can

The evolution in transparency and communication, the breakdown of the fortress, and everything else we have discussed about the new conditions in the twenty-first century enable us to see and affect culture on every level. We can identify, quantify, and systematize the dimensions of culture as never before, allowing us a unique opportunity to unleash its power and efficiency.

We Must

When I was asked to testify before the U.S. Federal Sentencing Commission when the committee was considering revisions to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, I made a passionate argument about the centrality of culture to business governance.

1

The committee heard from many other experts as well, and they incorporated these ideas into their new recommendations to judges dealing with corporate malfeasance.

2

The newest guidelines direct judges determining a company’s culpability for wrongdoing to evaluate an organization’s commitment to “promote an organizational culture that encourages ethical conduct and a commitment to compliance with the law.”

3

The U.S. Department of Justice, interpreting the committee’s findings, made it even more clear, saying, “A corporation is directed by its management and

management is responsible for a corporate culture

in which criminal conduct is either discouraged or tacitly encouraged.”

4

[italics added]

“Our work on the commission was nothing less than a battle for the hearts and minds of the people who work at companies,” Judge Ruben Castillo told me when we visited with each other in his chambers in Chicago.

5

Castillo is vice chair of the commission and has served as a U.S. district judge for the Northern District of Illinois since 1994. “The guidelines became more than just a way to reduce [incidents calling for] fines and punishment; they aspire to induce higher values and bring the business community to higher levels of conduct.” As we move forward into an ever more transparent world, culture—the character of an organization—is now everyone’s responsibility.

We Should

Culture can’t be copied. The collective experience of any group of people forms a unique narrative, a story that lives and breathes in the halls, offices, and factories of that enterprise. The way people connect, spark against one another to create new ideas or refine old ones, solve problems, and overcome adversity builds the synapses that make an organization thrive or die, and no two groups conglomerate these experiences alike. Each is as unique as any family; the number of children can be the same but the ties that bind them will always be unique. Because of this singularity, culture, as an expression of the collective HOWs of a group or enterprise, gives us our greatest opportunity for differentiation. Many of the people I spoke to agreed. “Culture is a competitive advantage that’s very, very hard to imitate,” Charles Hampden-Turner told me. “If you have a particular culture, another company can come along and seize your patent and try to imitate your product, but your culture has the huge advantage of both being real to the people who understand it and of being almost impossible to emulate. It doesn’t ‘scale up,’ as people like to say, because it is a process rather than a product.”

6

Just like we all know that one family can’t copy another, one company can’t copy another’s culture. I put this precise question to Massimo Ferragamo, chairman of Ferragamo USA, Inc., a subsidiary of Salvatore Ferragamo Italia, which controls sales and distribution of Ferragamo high-fashion products in North America. “Families cannot copy one another and companies cannot copy each other,” he told me.

7

Massimo is the youngest of six children of Salvatore and Wanda Ferragamo.

8

It was Salvatore Ferragamo who started the family shoemaking business at age 15 in Italy. Massimo followed in his father’s footsteps and began working in the family company at age 12, putting shoes into boxes. Today, he, his mother, his siblings, their children, and a slew of other relatives preside over a luxury fashion empire with more than 200 retail locations around the world. As they embark on the journey to take the company public, Massimo has had ample opportunity to think about what will make the family business endure in the new millennium. And for him, it boils down to culture. “It is the culture that is not copiable. It is values and deep things that are very hard to duplicate. Those values are established by someone naturally in the life of the company, often without them even knowing it, and then gets carried through the threads of people who embrace those values and culture. I would venture to say this: Our U.S. company and our Japanese company and our Italian company, in three different parts of the world, stand a much greater chance of having a similar culture that two unrelated companies that occupy the same building in Florence.”

Organizations can win through culture, by getting their HOWs right and setting off Waves of creativity and purpose throughout their workforce. Winning today requires surpassing expectation because great companies don’t just fulfill contracts; they exceed them. They outbehave the competition. “It means giving an experience that no one else can do,” Ferragamo told me, “and it is very, very challenging. It means excellence to the

n

th degree.”

I asked Massimo for an example of how he thinks he can outbehave his competition. “I was talking to a lovely lady who works in our company,” he said. “She was on holiday and passed by one of our stores that was extremely busy. She doesn’t work in our retail stores, but she went in and said, ‘Let me give you a hand.’ It was 10:30 in the morning and she didn’t leave until 5:30 that evening, and this was her

vacation

. During the day, a customer came in and said to her, ‘I have my Christmas shopping to do and I do not know what to do, and I am in a hurry.’ She said, ‘Look, do you have a list?’ He gave it to her. To make a long story short, he sat down with a drink and she just brought over things. He left with a six- or seven-thousand-dollar purchase, and I am sure she made his day. The challenge for me is how do I duplicate that commitment, not as a happenstance, but as a standard? How do I create a culture where we can play a great game and keep on scoring so that everyone can still be that excited by the game? That is how you outbehave competition.”

In an informed acquiescence culture, you could do everything that the carrots and sticks require, play by the rules, and still never

delight

or

surprise

anyone. Self-governance is about giving people the freedom to act individually and creatively, to uncork their ability to surprise people and create delight. In a world where your HOWs matter most, governing through culture puts the opportunity to exceed expectations in the hands of those who can make the difference.

FREEDOM IS JUST ANOTHER WORD

When most people first think of self-governance in the abstract, it seems all well and good. But when they think about it concretely, fear creeps in. How can an organization function, they ask, when workers are free to do what they want?

But what is freedom? Some people think that freedom is an absence of constraint. “If I could just do exactly what I want,” they think, “I could really get something done.” Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard had a different thought: “Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom,” he said.

9

Researchers at the University of Erfurt in Germany set up an investment game to discover exactly what freedom means to people—in dollars and cents. They recruited 84 players and gave them 20 tokens each. To make it interesting, and to ensure a real profit motive, they told the players they could redeem their tokens for real money at the end of the game. In each of a number of rounds, players could choose whether to invest some or none of their tokens in a fund. The fund had a guaranteed return, and after every round, the profit would be distributed to the entire group equally, including those free riders who chose not to invest.

10

The game was totally transparent; everyone could see what everyone else did. Those were the ground rules.