Hot Milk (16 page)

Authors: Deborah Levy

I could see Rose shuffling her legs, her left ankle twisting in her slipper, and I was not really sure who it was I was singing to, whether it was M or F or H or G or the fictive Godparent or even Ingrid Bauer. I could smell calamari being fried in the café in the square, but I was missing England, toast and milky tea and rainclouds. I heard my voice was very London because that’s where I was born, and then I left the room. My mother was calling to me, she called my name over and

over – ‘Sofia Sofia Sofia’ – and then she shouted, but it was not an angry shout, and I suppose I wanted my ghostly mother to rise from the shattered stars made in China and say

tomorrow is another day, you will land safely you will you will

.

I walked into the kitchen and on the table was the fake ancient Greek vase with the frieze of female slaves carrying jugs of water on their heads. I grabbed it and threw it on the floor. As it crashed and shattered, the venom from the medusa stings made me feel like I was floating in the most peculiar way.

When I looked up, my mother was standing – she was actually standing – in the kitchen among the shards of fake ancient Greece. She was tall. A cardigan was lightly draped over her shoulders. She had worked all her life and she had a driving licence, but she would have been neither a citizen nor a foreigner in ancient Greece. She would have had no rights in these ruins that were once a whole civilization which saw her as a vessel to impregnate. I was the daughter who had thrown the vessel to the floor and smashed it. My mother had tried to keep it together for a while. She taught herself how to make salty goat’s cheese for my father I remember I remember, warming the milk, adding the yogurt, stirring in the rennet, cutting the curds, doing something with muslin and brine, pickling cheese in jars. She put herbs on the lamb she roasted for him, herbs she had never heard of in Warter, Yorkshire, but when he left she could not pay the bills with herbs and cheese I remember, I do remember, she had to walk out of the kitchen and do something else, I remember she turned the oven off and put her coat on and she opened the front door and there was a wolf waiting for us on the mat but she chased it away and found a job and her lips were not puckered, her eyelashes were not curled when she sat in the library day after day indexing books, but her hair was always perfect and it was held up with one pin.

‘Sofia, what’s wrong with you?’

I started to tell her but a children’s entertainer in the square was

letting off firecrackers. I could hear the children laughing and knew he was on a unicycle, blowing fire out of his mouth. I looked at the broken pieces of the fake Greek vase and reckoned it was a sign to fly to my father in Athens.

My father was waiting for me at Athens International Airport, but he was not alone. I was alone with my suitcase and he was standing in the company of his new wife, who was holding their new baby daughter in her arms. I waved to him and the sound between us was the wheels of my suitcase on the marble floor. We had not seen each other for eleven years but we recognized each other with no hesitation. As I got closer he walked towards me and took my suitcase, then he kissed my cheek and said, ‘Welcome.’ He was tanned and relaxed. If anything his hair had become blacker, but I remembered it as silver, and he was wearing a blue shirt that had been ironed with care, its creases sharp at the elbow and collar.

‘Hello, Christos.’

‘Call me Papa.’

I’m not sure I can do that, but if I write it down I’ll see what it looks like.

As we made our way towards his new family, Papa asked me about the flight. Had I managed to have a nap and did they serve a snack and did I have a window seat and were the toilets clean, and then we were standing next to his wife and younger daughter.

‘This is Alexandra, and this is your sister, Evangeline. Her name means “messenger”, like an angel.’

Alexandra had short, straight, black hair and she was wearing spectacles. She was quite plain but young, and her blue denim shirt

(made by Levi Strauss) was damp from the milk in her breasts. She was sallow and looked tired. A steel brace was clamped across her front teeth. She peered at me from behind the lenses of her spectacles, and she was open and friendly, a little wary but, most of all, welcoming. I took a look at Evangeline, who also had black hair, lots of it. My sister opened her eyes. They were brown and lustrous, like rain glittering on a roof.

When my father and his new wife gazed down at Evangeline I could see the truest love in their eyes, the sort of love that is naked and without shame.

They were a family. They looked as right together as a 69-year-old man and a 29-year-old woman can possibly look. Mostly they looked wrong, like a father and daughter and grandchild, but as wrong goes, the affection between them was right. My father, Christos Papastergiadis, was caring for two new women. He had made another life, and I was part of the old life that had made him unhappy. To give myself courage I had pinned up my hair with three scarlet flamenco flower hairgrips I had bought in Spain.

He told me he would get the car and we were to wait outside at the pick-up point, then he gave me some information. Apparently, there was a bus – number X95 – parked right outside the airport exit. It cost five euro and I should know the next time I was in Athens that it would take me to Syntagma Square in the centre. Papa jangled the car keys above Evangeline’s head like a kindly grandfather and then disappeared through a glass door.

I asked Alexandra if she would like an iced coffee because I was about to buy one at the kiosk. She said no, the caffeine would get into her breast milk and Evangeline would become too excited. She smiled, and her teeth braces made her seem much younger than I am. I wondered if she had given birth wearing braces, but she was asking me what I did for a living, and I told her (sipping my frappuccino through a straw) that I hadn’t yet figured what to do with my anthropology degree.

‘Well, you should go have a look at the Parthenon. Do you know, it is the most important surviving building of classical Greece?’

I do know, yes.

She asked me again, because I had answered in my mind and not spoken the words out loud.

‘The Parthenon,’ she repeated.

‘I have heard of it, yes.’

‘The Parthenon,’ she said again.

‘It’s a temple,’ I said.

Alexandra wore slippers made from grey felt with white fluffy felt clouds glued on the toes. The clouds had two button eyes that rolled when she moved her feet. Do clouds have eyes? Sometimes storm clouds are represented as a face with puffed-out cheeks to suggest wind, but they don’t usually have rolling eyes. That’s because they were not clouds. They were lambs.

Alexandra saw me staring at her feet and she laughed. ‘They are comforting. I paid just less than seventy euro for them. Really, they are slippers for inside, but they have sturdy rubber soles so I can wear them outside.’

My father’s new bride child wore braces and animal shoes. My eyes started to roam around her, just in case I discovered ladybird earrings or a ring with a smiley face, but all I could see were two small moles on her neck and one just above her lip. I realized that my mother was sophisticated. Lurking behind the partition of her illness was a glamorous woman who knew how to put an outfit together.

The car arrived. Alexandra and Evangeline were helped into the back seat by Papa. I have said ‘Papa’ out loud and to myself a few times now and I quite like the sound of it. He took a while arranging the seat belt over Alexandra’s lap while she held the baby. He unfolded a small white sheet and spread it over her knees and told her in English to catch up on some sleep. He gestured to me to get into the front seat. My suitcase was in the boot and my father was driving us down the motorway towards Athens, all the time looking in the mirror to check

on the well-being of his family, smiling at Alexandra to reassure her he was here and not somewhere else.

‘Where are you living now, Sofia?’

I told him I slept in the storeroom at the Coffee House during the week and at Rose’s on weekends.

‘Are you having a good rest in Spain? Do you snooze in the afternoons?’

He often used words like ‘nap’, ‘snooze’, ‘rest’. I explained that I didn’t sleep much. Most nights, I lay awake, thinking about my unfinished Ph.D., and there were other duties, too, mostly to do with my mother, who was sick. I told him I could drive now. He congratulated me, then I explained how I didn’t have a licence but that was the next thing to do when I returned to London. When he heard Evangeline make a choking noise he said something to Alexandra in Greek, and she answered him back in Greek, and I didn’t understand a word. Papa explained there was a shortage of medicines due to ‘the crisis’ and they were concerned that Evangeline remained healthy. After a while, Alexandra asked me why I did not speak Greek. My father replied on my behalf in English.

‘Well, Sofia does not have much of an ear for languages. And she did not go to Greek school on Wednesdays and Saturdays, because her mother thought she had enough on her plate at English school.’

Actually, I had nothing on my plate at English school. I had soup in a flask and, sometimes, it was a Greek soup made with lentils.

‘Alexandra speaks fluent Italian. In fact, she is more Italian than Greek.’ My father beeped his horn twice.

I heard a high, childish voice whisper, ‘

Si, parlo Italiano

,’ and I jumped, which made my father swerve the car.

When I turned round to look at Alexandra, she was giggling, her hand clapped over her mouth. ‘Were you born in Italy then?’ I don’t know why I sounded so put out. Perhaps she had punctured my status as the only outsider sitting in the family car, which smelt of vomit and milk.

‘I don’t know for certain.’ She shook her head as if it were a mystery.

Identity is always difficult to guarantee.

I unpinned the flowers from my hair and let the tangle of curls fall past my shoulders. My lips were still cracking. Like the economies of Europe. Like financial institutions everywhere.

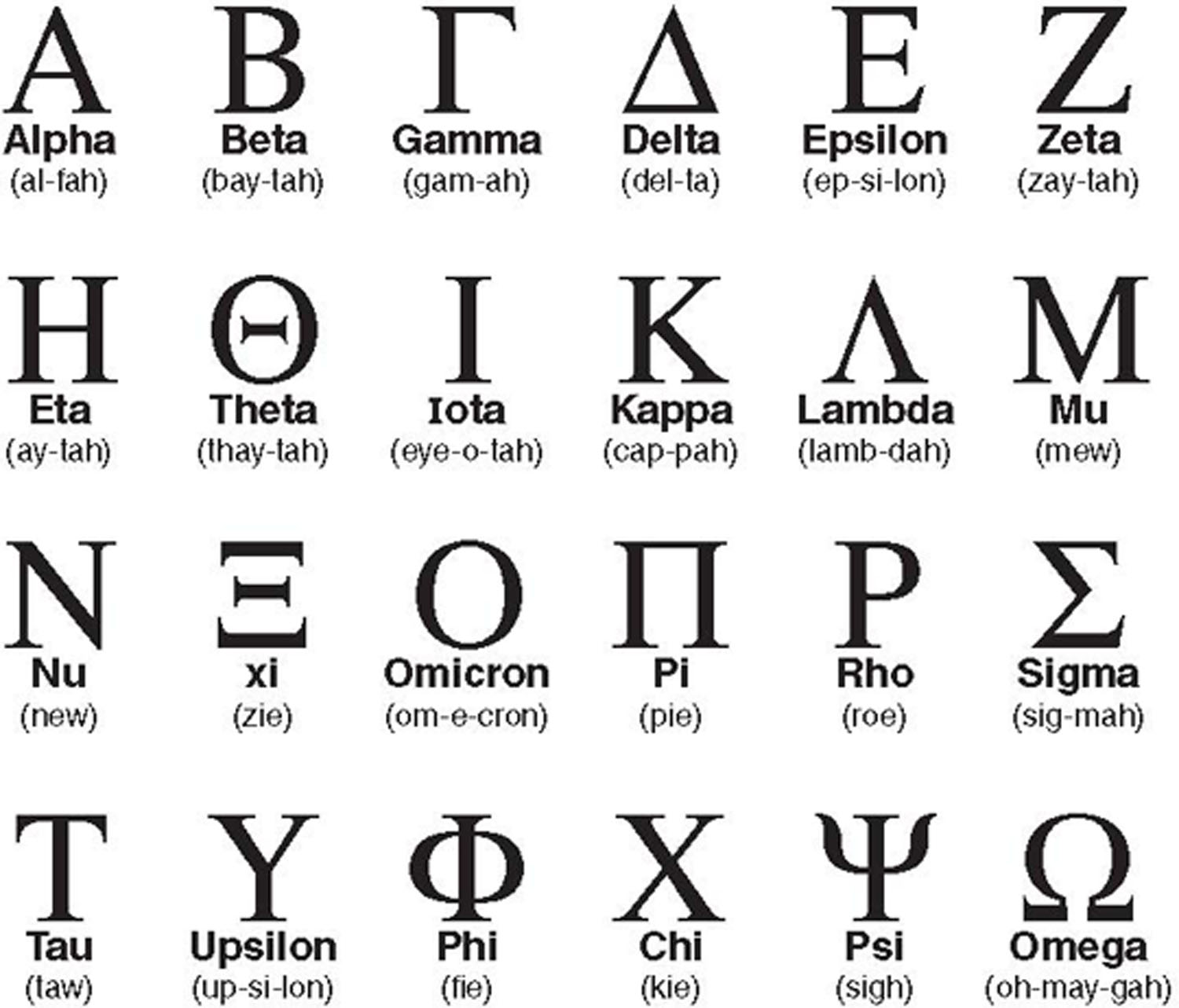

That night, I heard Papa singing to Evangeline in Greek when he put her to bed. My sister will have an ear for the language of her father. She will learn the alphabet with its twenty-four letters in its ancient and modern forms from alpha to omega.

Truest love will be her first language. She will learn to say ‘Papa’ from an early age and mean it. I have more of an ear for the language of symptoms and side effects, because that is my mother’s language. Perhaps it is my mother tongue.

The walls of their apartment in the leafy neighbourhood of Kolonaki are entirely covered with framed Donald Duck posters. Outside

their apartment, the walls are graffitied with ‘OXI OXI OXI’. Alexandra explained that ‘OXI’ in Greek means ‘no’. I said yes, I know

oxi

means no, but why so many ducks? Apparently they were digitally printed on to panels of plywood and arrived in the post with picture hooks in place for easy hanging. She said they cheered her up, because she had never seen any cartoons when she was a child. She pointed to Donald in a sailor outfit, Donald in a Superman outfit, Donald running away from a crocodile, Donald dressed in a purple wizard’s hat, Donald jumping through a hoop in a circus ring.

Alexandra smiled. ‘He is a child. He likes to have adventures.’

Is Donald Duck a child or a hormonal teenager or an immature adult? Or is he all of those things at the same time, like I probably am? Does he ever weep? What effect does rain have on his mood? When does he say no and when does he say yes?

My mother has seven Lowry prints hanging on the walls of her home. She likes his scenes of everyday life in the rain of industrial north-west England. Lowry’s own mother was ill and depressed, so he looked after her and painted at night while she slept. She and I never talk about that part of his life.

Alexandra asks my father to set the table for supper while she shows me the spare bedroom.

‘Don’t use the best plates,’ she says, but he knows that already. If my mother and Lowry’s mother were plates – not the best plates, but not the worst plates either – they would have the name of the place they were made stamped on the back: ‘Made in Suffering’.

The plates would be displayed on a shelf as heirlooms to be inherited by their unfortunate children.

My little sister, Evangeline. What will she inherit?

A shipping business.

‘Sofia,’ my father says. ‘I have put your flower hairclips on the table in your room. Alexandra will show you where it is.’

The spare bedroom has no windows. It is stifling. The bed is a hard canvas camping bed. It is a storeroom more than a bedroom,

just like my room at the Coffee House. Alexandra shut the door with intense focus so as not to wake Evangeline, making

sshh shhh

sounds, until, finally, when she had conquered its very last squeak, she tiptoed down the corridor in her lamb slippers. I lay down on the bed. Twelve seconds passed. I changed the position of the pillow and the bed collapsed to the floor, tipping over the little bedside table with my scarlet flower hairgrips neatly placed on it. Evangeline woke up and started to cry. I remained on the floor with the table lying across my chest and made cycling movements with my legs to stretch them after the plane journey. The door opened and my father walked in.