Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (2 page)

Read Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow Online

Authors: Yuval Noah Harari

Invisible Armadas

After famine, humanity’s second great enemy was plagues and infectious diseases. Bustling cities linked by a ceaseless stream of merchants, officials and pilgrims were both the bedrock of human civilisation and an ideal breeding ground for pathogens. People consequently lived their lives in ancient Athens or medieval Florence knowing that they might fall ill and die next week, or that an epidemic might suddenly erupt and destroy their entire family in one swoop.

The most famous such outbreak, the so-called Black Death, began in the 1330s, somewhere in east or central Asia, when the

flea-dwelling bacterium

Yersinia pestis

started infecting humans bitten by the fleas. From there, riding on an army of rats and fleas, the plague quickly spread all over Asia, Europe and North Africa, taking less than twenty years to reach the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. Between 75 million and 200 million people died – more than a quarter of the population of Eurasia. In England, four out of ten people died, and the population dropped from a pre-plague high of 3.7 million people to a post-plague low of 2.2 million. The city of Florence lost 50,000 of its 100,000 inhabitants.

6

Medieval people personified the Black Death as a horrific demonic force beyond human control or comprehension.

The Triumph of Death

,

c

.1562, Bruegel, Pieter the Elder © The Art Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

The authorities were completely helpless in the face of the calamity. Except for organising mass prayers and processions, they had no idea how to stop the spread of the epidemic – let alone cure it. Until the modern era, humans blamed diseases on bad air, malicious demons and angry gods, and did not suspect the existence of bacteria and viruses. People readily believed in angels and fairies, but they could not imagine that a tiny flea or a single drop of water might contain an entire armada of deadly predators.

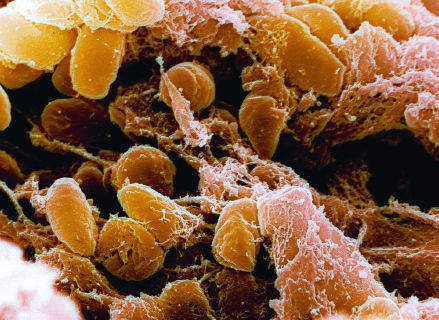

The real culprit was the minuscule

Yersinia pestis

bacterium.

© NIAID/CDC/Science Photo Library.

The Black Death was not a singular event, nor even the worst plague in history. More disastrous epidemics struck America, Australia and the Pacific Islands following the arrival of the first Europeans. Unbeknown to the explorers and settlers, they brought with them new infectious diseases against which the natives had no immunity. Up to 90 per cent of the local populations died as a result.

7

On 5 March 1520 a small Spanish flotilla left the island of Cuba on its way to Mexico. The ships carried 900 Spanish soldiers along with horses, firearms and a few African slaves. One of the slaves, Francisco de Eguía, carried on his person a far deadlier cargo. Francisco didn’t know it, but somewhere among his trillions of cells a biological time bomb was ticking: the smallpox virus. After Francisco landed in Mexico the virus began to multiply exponentially within his body, eventually bursting out all over his skin in a terrible rash. The feverish Francisco was taken to bed in the house of a Native American family in the town of Cempoallan. He infected the family members, who infected the neighbours. Within ten days Cempoallan became a graveyard. Refugees spread the disease from Cempoallan to the nearby towns. As town after town succumbed to the plague, new waves of terrified refugees carried the disease throughout Mexico and beyond.

The Mayas in the Yucatán Peninsula believed that three evil gods – Ekpetz, Uzannkak and Sojakak – were flying from village to village at night, infecting people with the disease. The Aztecs blamed it on the gods Tezcatlipoca and Xipe, or perhaps on the black magic of the white people. Priests and doctors were consulted. They advised prayers, cold baths, rubbing the body with bitumen and smearing squashed black beetles on the sores. Nothing helped. Tens of thousands of corpses lay rotting in the streets, without anyone daring to approach and bury them. Entire families perished within a few days, and the authorities ordered that the houses were to be collapsed on top of the bodies. In some settlements half the population died.

In September 1520 the plague had reached the Valley of Mexico, and in October it entered the gates of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan – a magnificent metropolis of 250,000 people. Within two months at least a third of the population perished, including the Aztec emperor Cuitláhuac. Whereas in March 1520, when the Spanish fleet arrived, Mexico was home to 22 million people, by December only 14 million were still alive. Smallpox was only the first blow. While the new Spanish masters were busy enriching themselves and exploiting the natives, deadly waves of flu, measles and other infectious diseases struck Mexico one after the other, until in 1580 its population was down to less than 2 million.

8

Two centuries later, on 18 January 1778, the British explorer Captain James Cook reached Hawaii. The Hawaiian islands were densely populated by half a million people, who lived in complete isolation from both Europe and America, and consequently had never been exposed to European and American diseases. Captain Cook and his men introduced the first flu, tuberculosis and syphilis pathogens to Hawaii. Subsequent European visitors added typhoid and smallpox. By 1853, only 70,000 survivors remained in Hawaii.

9

Epidemics continued to kill tens of millions of people well into the twentieth century. In January 1918 soldiers in the trenches of northern France began dying in their thousands from a particularly virulent strain of flu, nicknamed ‘the Spanish Flu’. The front line was the end point of the most efficient global supply network the world had hitherto seen. Men and munitions were pouring in from Britain, the USA, India and Australia. Oil was sent from the Middle East, grain and beef from Argentina, rubber from Malaya and copper from Congo. In exchange, they all got Spanish Flu. Within a few months, about half a billion people – a third of the global population – came down with the virus. In India it killed 5 per cent of the population (15 million people). On the island of Tahiti, 14 per cent died. On Samoa, 20 per cent. In the copper mines of the Congo one out of five labourers perished. Altogether the pandemic killed between 50 million and 100 million people in less than a year. The First World War killed 40 million from 1914 to 1918.

10

Alongside such epidemical tsunamis that struck humankind every few decades, people also faced smaller but more regular waves of infectious diseases, which killed millions every year. Children who lacked immunity were particularly susceptible to them, hence they are often called ‘childhood diseases’. Until the early twentieth century, about a third of children died before reaching adulthood from a combination of malnutrition and disease.

During the last century humankind became ever more vulnerable to epidemics, due to a combination of growing populations and better transport. A modern metropolis such as Tokyo or Kinshasa offers pathogens far richer hunting grounds than medieval Florence or 1520 Tenochtitlan, and the global transport network is today even more efficient than in 1918. A Spanish virus can make its way to Congo or Tahiti in less than twenty-four hours. We should therefore have expected to live in an epidemiological hell, with one deadly plague after another.

However, both the incidence and impact of epidemics have gone down dramatically in the last few decades. In particular, global child mortality is at an all-time low: less than 5 per cent of children die before reaching adulthood. In the developed world the rate is less than 1 per cent.

11

This miracle is due to the unprecedented achievements of twentieth-century medicine, which has provided us with vaccinations, antibiotics, improved hygiene and a much better medical infrastructure.

For example, a global campaign of smallpox vaccination was so successful that in 1979 the World Health Organization declared that humanity had won, and that smallpox had been completely eradicated. It was the first epidemic humans had ever managed to wipe off the face of the earth. In 1967 smallpox had still infected 15 million people and killed 2 million of them, but in 2014 not a single person was either infected or killed by smallpox. The victory has been so complete that today the WHO has stopped vaccinating humans against smallpox.

12

Every few years we are alarmed by the outbreak of some potential new plague, such as SARS in 2002/3, bird flu in 2005,

swine flu in 2009/10 and Ebola in 2014. Yet thanks to efficient counter-measures these incidents have so far resulted in a comparatively small number of victims. SARS, for example, initially raised fears of a new Black Death, but eventually ended with the death of less than 1,000 people worldwide.

13

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa seemed at first to spiral out of control, and on 26 September 2014 the WHO described it as ‘the most severe public health emergency seen in modern times’.

14

Nevertheless, by early 2015 the epidemic had been reined in, and in January 2016 the WHO declared it over. It infected 30,000 people (killing 11,000 of them), caused massive economic damage throughout West Africa, and sent shockwaves of anxiety across the world; but it did not spread beyond West Africa, and its death toll was nowhere near the scale of the Spanish Flu or the Mexican smallpox epidemic.

Even the tragedy of AIDS, seemingly the greatest medical failure of the last few decades, can be seen as a sign of progress. Since its first major outbreak in the early 1980s, more than 30 million people have died of AIDS, and tens of millions more have suffered debilitating physical and psychological damage. It was hard to understand and treat the new epidemic, because AIDS is a uniquely devious disease. Whereas a human infected with the smallpox virus dies within a few days, an HIV-positive patient may seem perfectly healthy for weeks and months, yet go on infecting others unknowingly. In addition, the HIV virus itself does not kill. Rather, it destroys the immune system, thereby exposing the patient to numerous other diseases. It is these secondary diseases that actually kill AIDS victims. Consequently, when AIDS began to spread, it was especially difficult to understand what was happening. When two patients were admitted to a New York hospital in 1981, one ostensibly dying from pneumonia and the other from cancer, it was not at all evident that both were in fact victims of the HIV virus, which may have infected them months or even years previously.

15

However, despite these difficulties, after the medical community became aware of the mysterious new plague, it took scientists just two years to identify it, understand how the virus spreads and

suggest effective ways to slow down the epidemic. Within another ten years new medicines turned AIDS from a death sentence into a chronic condition (at least for those wealthy enough to afford the treatment).

16

Just think what would have happened if AIDS had erupted in 1581 rather than 1981. In all likelihood, nobody back then would have figured out what caused the epidemic, how it moved from person to person, or how it could be halted (let alone cured). Under such conditions, AIDS might have killed a much larger proportion of the human race, equalling and perhaps even surpassing the Black Death.

Despite the horrendous toll AIDS has taken, and despite the millions killed each year by long-established infectious diseases such as malaria, epidemics are a far smaller threat to human health today than in previous millennia. The vast majority of people die from non-infectious illnesses such as cancer and heart disease, or simply from old age.

17

(Incidentally cancer and heart disease are of course not new illnesses – they go back to antiquity. In previous eras, however, relatively few people lived long enough to die from them.)