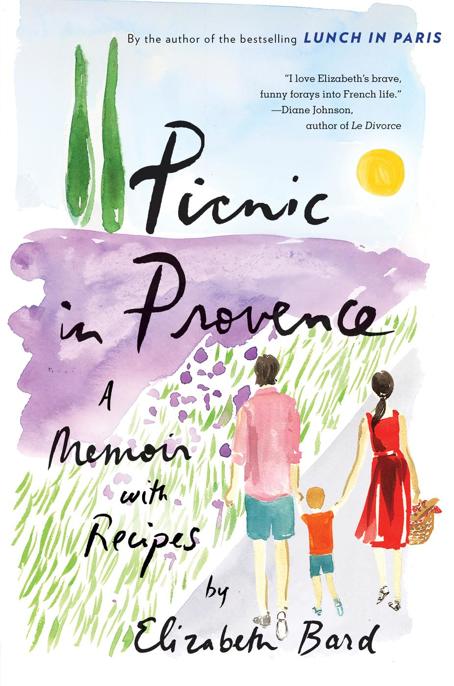

Picnic in Provence

Read Picnic in Provence Online

Authors: Elizabeth Bard

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For my mother.

Now I get it.

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect people’s privacy. Once again, poor Gwendal didn’t get that lucky.

I

don’t, as a rule, introduce myself to cows. But these were important cows, essential ones. If for some reason they weren’t available, our dream of locally made Provençal ice cream would be dead before it began.

“Hello, ladies,” I said gamely, noting the bones jutting out from their hindquarters. To an American, they seemed a bit svelte for good lavender ice cream. But this is France, so it shouldn’t surprise me that even the livestock look like they’re on a diet. The cows observed me with perfect detachment as my heels sank into the early-spring mud. One finally looked up and gave me her full attention. She chewed thoughtfully on a mouthful of hay, her large liquid eyes perfectly ringed with black, like Elizabeth Taylor in

Cleopatra.

Suddenly her head bobbed down toward my boots and immediately back up again, as if to say,

Excusez-moi, madame, but it’s clear from the cleanliness of your shoes that you’re new around here. Very, very new. And, as a rule, we don’t produce milk for anyone born in Manhattan.

If you had told me on my wedding day that ten years later I’d be standing in a field in Provence making small talk with skinny cows, I would have nodded politely and with a twist of my graduated pearls, said that you must have mistaken me for someone else.

I would have been wrong.

WE DIDN’T COME

to stay. We had no intentions beyond a few days of sun and a busty bottle of Côtes du Rhône.

Céreste, an hour east of Avignon, is not what you’d call the chic part of Provence. It’s a village of thirteen hundred tucked into a valley along the old Roman road; the locals are accustomed to tourists passing through on their way to more scenic hilltop towns—Saignon, Lourmarin—nearby. There is a single main street with a butcher, two

boulangeries

, and a café with plastic chairs and a thatched awning. From the moment you drive into town at the roundabout near the blinking neon cross of the pharmacy to the moment you drive out under a canopy of towering plane trees is about twenty-five seconds. If you duck to rummage in the glove compartment for an extra pair of sunglasses, you might miss it. But here we were, one exhausted French executive and his pregnant American wife, staying for ten days over the Easter holidays.

Gwendal and I rolled our bags, wheels noisy as a stagecoach, through the stone-paved courtyard of the B&B. La Belle Cour is a gracious house, full of books, sofas with deeply dented cushions, and the grave ticktocking of grandfather clocks. As we climbed the spiral stairs to our room (no one offered me a piggyback, though I might have accepted it), I ran my hand along the white plaster walls, chill to the touch. The plumped-up pillows on the bed were welcoming. I sat down, eased down, really, with my belly in the lead, on the quilted chenille spread.

I thought of another set of spiral stairs, three flights up to a cramped love nest in the heart of Paris. Ten years ago, I had lunch with a handsome Frenchman—and never quite went home. My French lover is now my French husband, and I’m an adopted

Parisienne

. I know which local bakery makes the best croissants, I can speak fluently to the man at the phone company (a bigger accomplishment than it sounds), and I can order a neatly flayed rabbit from the butcher without the slightest hesitation.

We had spent the past five years in nearly constant motion. Gwendal founded a successful consulting company and realized his dream of working in the cinema industry. I had made the precarious transition from part-time journalist to full-time author. My first book, as well as our first child, was on the way. We had a flat with a working fireplace and some semblance of a bathtub. In our mid-thirties, deeply in love (if completely exhausted), it was all coming together. When I was a child, I had projected myself ahead to this place; I’d waited my whole life to sit atop a well-tended mountain of accomplishments, admiring the view. But lately, there was another feeling creeping in. Call it lack of oxygen. Battle fatigue. Maybe it was just the baby pressing firmly against my bladder, but it felt more and more like the mountain was sitting on top of us.

When we came down dressed for dinner, there were already four glasses and a bottle of rosé on the wrought-iron table outside. Our English hostess, Angela, appeared with a plate of

gressins,

bread sticks long and thin as a flapper’s cigarette holder, and a small bowl of candied ginger. She was tall and elegant with finishing-school posture, her shoulders draped in layers of cotton and cashmere with a dangle of silver earrings. Something in the way she kept her quick smile in reserve told me that she was the funny one. Her husband, Rod, wore pastel stripes that matched his pink cheeks. He had the bright eyes of someone who enjoyed crying at weddings, and movies. We liked them instantly. “So what brings you to Céreste?” asked Rod, pouring a blush of wine into Gwendal’s glass. Though no one ever got arrested for having a glass of wine while pregnant—particularly in France—I contented myself, begrudgingly, with sparkling water.

Gwendal paused, trying to come up with an answer that wouldn’t sound too much like we were on a pilgrimage. My husband is a great admirer of the French poet and World War II Résistance leader René Char. We knew Char had lived in Céreste during the war. Because I was entering my third trimester and wary of flying, we’d decided to explore the Luberon, the landscapes and events described in Char’s most famous poems. If that sounds like an odd premise for a holiday, well, I suppose it is. Then again, some people bird-watch.

As soon as we mentioned Char, Angela put down her glass, disappeared inside the house, and returned with a small white paperback. “Have you read the latest book?”

As it turns out, history was living just up the road. During the war, Char had a passionate affair with Marcelle Pons Sidoine, a young woman from the village. They lived together and ran the local Résistance network from her family’s home. Marcelle had a daughter, Mireille, who was eight years old in 1940. “She just published a book about her childhood with René Char,” said Angela. “They’re only a few houses up. On the left. Would you care to meet her?”

Gwendal’s eyes got excited, then bashful. I could see his French brain ticking away:

But what will I say to a perfect stranger?

It takes more than ten years in bed with an American to cure a European of his natural reserve. In the end, curiosity trumped culture—there was no question of refusing.

A phone call was made, polite greetings exchanged. Mireille would be happy to see us in a few days’ time.

OUR APPOINTMENT FIXED

, we settled in to explore the region. The next morning, while I read my book in the flower-filled courtyard, Gwendal went hiking. He needed to walk off the last few months at work. Two years earlier, he had merged his little company with a larger entity and worked his ass off (he belongs to the rare genus of French workaholics). Now he found himself at the point where he no longer had strategic control. He was like one of those mimes pushing at the ceiling of an invisible box; he had a great salary, a fancy title, but was trapped nonetheless. Angela and Rod sent him up the trail behind the local cemetery to the neighboring village of Montjustin. On a clear day you can see the snow-white summits of the Alps. Gwendal returned at noon, his dark hair slick with sweat, his boots muddy. As much as I like him in a suit and tie, I had to admit he looked five years younger in his shorts.

Even if I hadn’t been six months pregnant, it’s debatable how much hiking I might have done. Gwendal, raised on the wild Brittany coast, has always had a closer relationship to nature than I have. He likes panoramic views, the breeze coming up off the cliffs ruffling his hair and filling his lungs like white spirit. Me, I’m an asphalt princess, born and raised. I like the breeze coming up off the subway grates, ruffling my skirt and tickling my thighs, like Marilyn Monroe. The view I like best is of a well-laid dinner table.

To that end, we had some shopping to do. The B&B didn’t serve meals, and since most afternoons were already a balmy seventy-five degrees, Gwendal and I decided to picnic. Ten miles to the west, down a road that hugs the curves of the Luberon hills, the market in Apt is an institution in this part of Provence. Every Saturday from eight in the morning to twelve thirty in the afternoon, it takes over the entire town, from the parking lot on the outskirts of the old city, through the narrow arches with their pointed clock towers, down the cobblestoned streets, into each alley, onto every

placette

—a jumble of cheese, vegetables, sausage, and local lavender honey.

Over the years, French markets have become my natural habitat. It’s fair to say that almost everything I’ve learned about my adopted country I’ve learned

autour de la table

—around the table. The rituals of shopping for, preparing, and sharing meals have become such an integral part of my life in France, it’s difficult to remember those days in New York when lunch was the fifteen minutes it took me to walk to the Chinese salad bar and back to my desk.

We had made our way no farther than the first archway when I was stopped in my tracks by the scent of strawberries. Not the sight; simply the smell. Over the heads of several passersby, I spotted a folding table and a dark-haired mother-daughter team arranging rows of small wooden baskets. The berries were heart-shaped with neat crowns of green leaves. They were smaller and lighter in color than the bloodred monsters that normally came our way from Spain.

We had been warned that Easter was the beginning of the tourist season, and sure enough, the prices were strangely Parisian, higher even. But a girl’s got to eat. More specifically, she’s got to eat the season’s first strawberries from Carpentras, a purely local privilege. I bought one basket for us and one for Angela, and I asked the dark-haired woman to put them aside for later. I had a feeling we were going to end up with a lot to carry.

We passed a man selling quail’s eggs, tiny and spotted, the real ones barely distinguishable from their Easter candy equivalents in the window of the

chocolatier

. Neat bundles of the first asparagus were laid gently on pallets of straw. Resistance was futile. I felt certain that if I asked nicely, Angela would lend me a pot and a spot at her stove to blanch them.

Our steps slowed behind the growing morning crowd. There was a bottleneck up ahead at the

boulangerie

. A wrought-iron cart, a more elegant version of the pretzel vendors’ on the streets of New York, was posted outside. In addition to croissants and

pains au chocolat,

it was loaded with flattish ovals of yeasted bread. Some were covered with grated Gruyère cheese and bacon, some with a tangle of caramelized onions and anchovies. The script on the chalkboard sign said

Fougasse,

which I took to be a type of local focaccia. I leaned toward one topped with toasted walnuts, pungent with the smell of recently melted Roquefort cheese. This would be the perfect bread for our picnic, easy to tear and just greasy enough to give me an excuse to lick my fingers.

The crowd on the main pedestrian street was beginning to resemble Times Square’s on New Year’s Eve, all shuffling steps and jutting elbows. The weight of numerous plastic bags cut into my wrist, and I began to see the virtue in the brightly colored straw baskets on sale next to the Swiss chard. We ducked into a side street, passed stalls heaped with bolts of brightly colored cloth and bowls of glistening green olives, and entered a small square. I surveyed the morning’s haul. All we were missing was that essential French food group:

charcuterie

. I approached an unmarked white van, the kind your mother warned you never to get into. The side of the van opened to reveal a pristine stainless-steel counter and a display case. It was packed with thick-cut pork chops, fresh sausages flecked with herbs, even

boudin noir maison,

homemade blood sausage (not very practical for a picnic, but I couldn’t help plotting how I might get several lengths back to Paris in my suitcase). I settled on a

saucisse sèche au thym

—a horseshoe of dried sausage flavored with fresh thyme and black peppercorns. I was pretty sure Gwendal had remembered his father’s pocketknife.

Shopping for food in France never fails to make me hungry. Armed with a few days’ worth of supplies, we were more than ready for lunch.

THE FOLLOWING TUESDAY

, we arrived promptly at three for coffee with Mireille, the daughter of Char’s wartime love. She greeted us at the door, a dark-haired woman in her seventies wearing a wool skirt, sensible shoes, and a pink cotton blouse with a matching scarf. We walked under the stone vaults of the meticulously renovated seventeenth-century coaching inn she shared with her husband and her mother, Marcelle, now ninety-four. We were on the ground floor, the former kitchen of the inn. The stone hearth of the fireplace was almost large enough for me to step into. It was easy to imagine a hulking great cauldron of daube or

soupe d’épeautre

hung low over the embers, ready to greet the travelers who stopped to water their horses and left at first light.

A table was set by the only window. On the starched white cloth were a wooden pencil case and a pair of leather-covered headphones attached to a tangle of aging wire. They looked like props for an old-fashioned magic show. I wasn’t sure what to expect. Up until that moment, René Char was little more to me than a name on our bookshelf.

When you marry a foreigner—when you

are

the foreigner—cultural references are one of the widest gaps to leap. Gwendal and I worshipped at different altars. When we met, he had never seen

The Breakfast Club;

I’d never seen

Les 400 Coups.

My first slow dance was to Wham!; his was to some Italian pop star I’d never heard of. My adolescent angst (such as it was) was fueled by John Donne; Gwendal preferred Rimbaud. I won’t bother to tell you what happened the first time I tried to get him to eat a Twinkie. I consider myself a reasonably well-read English major, but except for the snippets Gwendal read aloud when he was particularly impressed, René Char’s poetry and history were new to me.