Hitching Rides with Buddha: A Journey Across Japan (36 page)

Read Hitching Rides with Buddha: A Journey Across Japan Online

Authors: Will Ferguson

The sky darkened and the storm hit, strafing the deck with rain, and then—we were through. We broke free of the storm and we were out at sea, with only horizons of waves stretching in all directions. I went back onto the deck, feeling immortal. On the far edge of the sea, rising above the water like a whale’s back, was Sado Island.

Night was falling and the island of Sado began to fade into darkness as we approached, becoming more and more indistinct the nearer we came.

By the time we reached Sado, Sado had disappeared.

C

OLD

W

IND

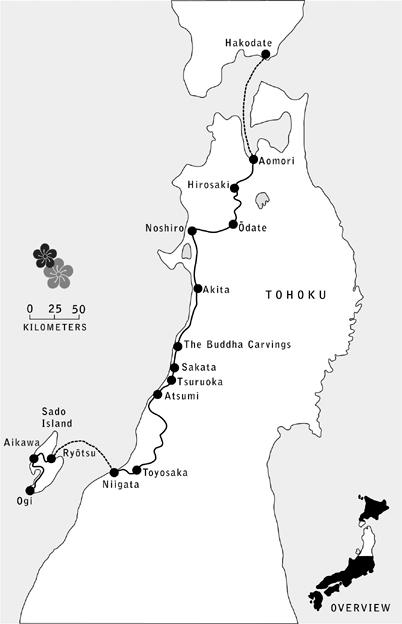

Sado Island and Tohoku

1

S

ADO HAS ALWAYS

been Japan’s Island of Exile.

It is a cold, distant, mythical place.

When the Emperor Juntoku led a failed revolt in 1221 against the Kamakura shōgunate, it was unthinkable to execute the Son of Heaven, even a disgraced, unruly, twenty-four-year-old ex–Son of Heaven stripped of his imperial crown. So, instead of sending Juntoku to his death for the abortive coup, they sent him here, to Sado.

In a few instances, exile in Sado was the prelude to greatness. Such was the case of the radical priest Nichiren, sent to the island in 1271.

What can you say about a man like Nichiren? He was certainly one of the most forceful personalities in Japanese history. If Kōbō Daishi was a Christlike figure healing the lame, curing the sick, and preaching inclusion, Nichiren was John the Baptist: an Old Testament–style prophet, all thunder and bluster and bile.

He was, above all, a fundamentalist. A self-described “son of an outcast fisherman,” Nichiren was disdainful—and no doubt envious—of the Court Buddhism of his day, with its manorial holdings and refined airs. In sharp contrast to its gentility, Nichiren went back to basics, to the original teachings of the Buddha—and the Lotus Sutra in particular. Not only did he reject the cozy, established Buddhist orders of his day, he also denounced the esoteric seclusion of Zen monasteries.

Nichiren was the first true Japanese nationalist. He was fervent in his vision of a trans-Nippon unity, a mother tribe at odds with the rest of the world. Nichiren was acutely aware of belonging to a nation; it wasn’t a particular valley or village or prefecture to which he swore

allegiance. His mission was to unite and purify all of Japan. He wanted the government to create—and enforce—a unified state religion.

Between 1257 and 1260, an unprecedented series of calamities ripped through central Japan: earthquakes, epidemics, famines, floods. Nichiren took this as a sign that the end was nigh. The gods were abandoning Japan. He prophesied that these events would culminate with a foreign invasion that would conquer the nation and destroy the Kamakura shōgunate, turning the Islands of Harmony into a vassal state—unless, that is, Nichiren’s obscure sect was made the official religion of Japan.

It was little more than spiritual blackmail, and the Shōgun could stand no more. Nichiren was sentenced to die by execution for insulting the rulers and inciting rebellion. What happened next is a little unclear, but legend has it that just as the executioner raised his sword to decapitate Nichiren—who was kneeling deep in prayer—a lightning bolt lashed out, breaking the sword in two.

Unnerved, the Shōgun decided instead to send the troublesome priest into exile, and so it was that Nichiren arrived on the lonely island of Sado. The small band of followers whom he left behind, who had never numbered more than three hundred, were rounded up, imprisoned, or run out of town. Their goods were confiscated and sold. It marked what should have been the end of the Nichiren movement.

For three long years, Nichiren lived on Sado, at first in an abandoned temple and later with a handful of followers who had made their way to the island. Racked with pain and in constant bad health, Nichiren nevertheless returned to his proselytizing ways, preaching the word of Buddha as he saw it and vehemently condemning all other sects. Slowly, ineluctably, he began to win over new recruits. Sado became a Nichiren stronghold, and his displaced sect—a cult really—took fresh root on this distant, windswept isle. The Kamakura shōguns had not heard the last of him.

While Nichiren was walking the backroads of Sado, news came to the capital of a Mongol army that was massing its warships off the coast of Korea. A wave of fear swept through the courts of Japan. Kublai—the Great Khan, grandson of Genghis, Scourge of Mongolia, Lord of China, Conqueror of Korea—had now turned his gaze upon the Land of the Rising Sun. The Shōgun, desperate and

repentant, sent for Nichiren. His past sins hastily pardoned, Nichiren began praying day and night for the salvation of the motherland.

The summer of 1274. A flotilla of warriors, twenty-five-thousand strong, crossed the straits separating the Korean peninsula and the archipelago of Japan. They landed in waves. There to meet them were armies of the samurai lined up in formation, waiting. What happened next was closer to farce than epic.

The samurai generals, following the formal codes of Japanese culture, rode out ahead of their men to formally greet and confront the enemy. Protocol demanded a speech and a verbose challenge with much posturing and sword-rattling bravado—much like the long, tense buildups that precede a sumo bout. In Japan, opposing generals would take turns striding forth on horseback to issue a stirring bit of bombast, boasting about the strength of their army, the honour of their ancestors, the prestige of their family names, and so on. Once all the opening formalities were over—which you can still see today in the endless speeches given before any event in Japan, no matter how minor—the battle would formally commence. It was all very civilized and proper, after which there would be general carnage and bloodletting.

Unfortunately, no one thought to explain the codes of etiquette to the Mongol hordes. And let’s face it, Mongol hordes are not really known for their etiquette and good manners. When the first Japanese general rode out and launched into a speech, the Mongols listened for a bit and then riddled his body with arrows. As the general toppled from his horse in mid-sentence, the samurai fell back in confusion. Clearly, this was not going to go according to plan. (And let me just say, as a veteran of many a long-winded Japanese speech, that I have the utmost sympathy for the Mongols. Many’s the time I wished I was armed with my own contingent of archers to cut short the usual bloated oratory of morning meetings. “Together we must strive harder and endeavour to meet the departmental goals as outlined in the—

thwwaaaacckk! AWK

!”)

With that first, ill-mannered volley, the invasion of Japan had begun. The Mongols poured in, strengthened their beachhead, and set perimeter encampments; they moved up, dug in. The battle raged in sporadic and sudden bloody engagements like a gory game

of tug-of-war. And then, far from the field of battle, stirring the skies like a cauldron, the prophet-priest Nichiren called forth a wind from the gods, a

kami-kaze

, which blew through, scattering the ships and sending the Mongols back in disarray. Japan had been spared.

But Mongol hordes are nothing if not persistent, and Kublai Khan immediately laid plans for a second strike. The Shōgunate scrambled to strengthen its position and build a fleet of light, quick-running warships. They constructed stone walls along the southern coast of Japan to keep the Mongols out, much like the Great Wall of China itself, which had also been built to stop them—and had failed.

Seven years passed. The horizon darkened once again with the sight of ships approaching. It was the largest naval invasion the world had ever seen, an army one hundred forty thousand strong. The Shōgun’s defensive walls contained them, barely, and all summer long the samurai armies battled back the Mongol, Korean, and Chinese soldiers. Thousands of bodies lay strewn along the coast, and the tides ran red as the clashes grew more frantic.

And then it came—again. Blowing in like a fury unleashed, a second typhoon, even greater than the first. The Mongols tried to fall back, across the strait to safe harbour in Korea, but the ships collided with each other and were sunk by the storm. More than four thousand Mongol ships went down—four thousand, mind you—taking with them over one hundred thousand men. Those left behind, or who managed to swim to shore, found themselves, in the wreckage of the storm’s passage, stranded without supplies and facing a full-frontal assault by the armies of the Japanese Shōgun. What followed was a massacre. The samurai pushed the remnants of the Khan’s army out onto a sandspit. Vanquished, the invaders threw down their swords and begged for mercy. They were butchered. Men died by the tens of thousands. It was a complete and utter rout, and when his few remaining ships limped back home, Kublai Khan had had enough. With the very gods against him, he abandoned his plans of conquest.

The Japanese Shōgun maintained a vigil along the coast for more than twenty years, but the Mongols never returned and the walls eventually crumbled (the ruins are still visible on the outskirts of modern Fukuoka City). Japan was the only kingdom in the Far East

not conquered by the Mongols. Indeed, Japan had never been conquered by any nation, ever, and would remain undefeated for seven hundred years—until 1945.

Kublai Khan’s failed invasions were a godsend to Nichiren. By predicting them, and then calling forth the kamikaze to defeat them, Nichiren had demonstrated his power and prophecy for all to see. True, hundreds of monks and priests, the Shōgun, and even the Emperor himself had also prayed for the gods to save their land, but it was Nichiren who took the credit. His sect flourished. The numbers grew, the persecution ended.

Today, seven centuries later, Nichiren-shō lives on. Sōka Gakkai, a subsect of Nichiren, has even formed its own political party, a blending unheard of in most developed countries. Today’s Sōka Gakkai Party, heir of Nichiren, stands against corruption and for clean government, and in its rhetoric one still hears the thunder and echo of Nichiren’s own righteous battle cry.

“I am the pillar of Japan, the eyes of Japan, protector of the nation!” This was Nichiren’s immodest boast, written during his long exile on Sado. And it is on Sado that he is best remembered: the prophet cast off, the voice in the wilderness, defiant and unbeaten.

Night. Falling snow. The town of Ogi was small but confusing. Streets led you inward only to abandon you. After trudging up one narrow lane and down another, I eventually stumbled upon a noodle shop, which I entered with a gust of cold air, eliciting frowns and hard stares from the patrons who sat hunched over steaming bowls. The men looked up as though I had interrupted a conspiracy.

“Hi there!” I said.

The noodle lady shot a glance in my direction and said, more sharply than was necessary, “No more service!” even as she ladled out another bowl of broth and slithering noodles. I talked my way into a space along the counter, but I had to put up with disgruntled silence as I ate. Where was the youth hostel?

Up the hill

. Where?

Up the hill, up the hill!

A hand waved, taking in several directions and leaving me without bearings or welcome.

Outside, the town was deserted and the snow was sifting down, dusting the streets and accenting the rooftops. I eventually called

the hostel from a lonely pay phone. The woman who answered—her voice as weary as might be expected of someone dealing with a simpleton—gave me directions that were only marginally more coherent than

Up the hill! Up the hill!

Sado Island is nothing

but

hills, I grumbled, and set off.

The road wound deep into a hidden valley. In the chilled white moonlight the rice fields were ridges of bone. A dog barked psychotically, almost choking on its saliva, as I approached a farmhouse. We faced off in the darkness. “Don’t worry, Will. He’s as scared of you as you are of him,” I said, unsuccessfully trying to convince myself to be brave.

I stood there, my very presence egging the dog on to more and more outlandish threats. “First I’m gonna rip your head off! Then I’m gonna chew your skull! Then I’m gonna—” The front door slid open and a woman in an apron came out and cursed the dog into silence.