Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family (6 page)

Read Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family Online

Authors: Robert Kolker

*

The idea of sterilizing the insane and “feeble-minded” had caught on in America many years earlier. Eugenics was a hallmark of the turn-of-the-century Progressive Era in America, influencing Kallmann and Rüdin and, among others, the Nazis.

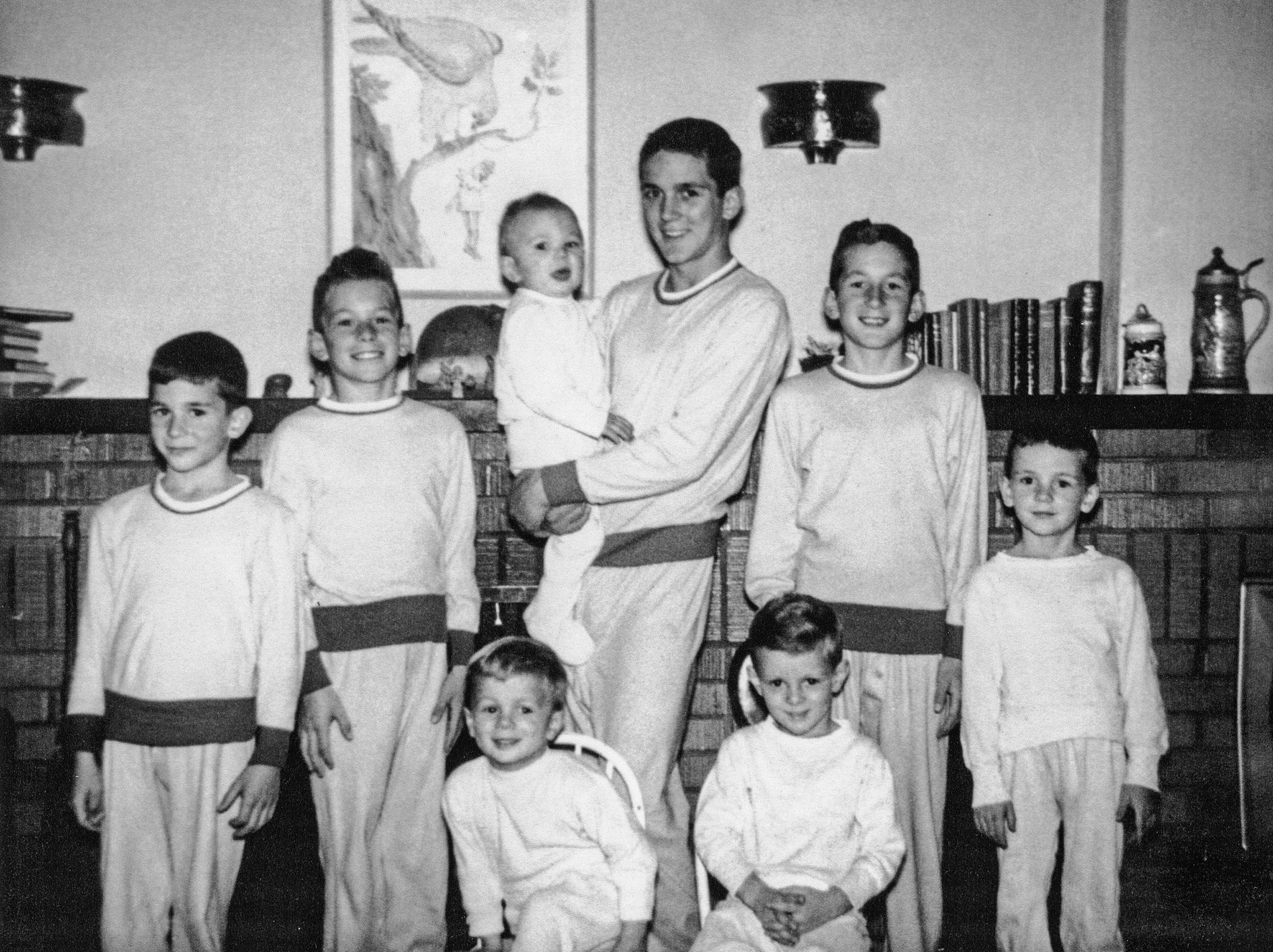

DON

MIMI

DONALD

JIM

JOHN

BRIAN

MICHAEL

RICHARD

JOE

MARK

MATT

PETER

MARGARET

MARY

When, after four years of out-of-town postings, the Galvins returned to Colorado Springs in 1958, the dusty town they’d left behind was fading into history. The United States Air Force Academy had opened while they were gone, and thousands of newcomers—cadets and their instructors and all the personnel needed to support a vast new military institution—were swiftly changing the character of the place. Where once there had been a dirt road with a couple of ruts, crossed by barbed wire gates that you had to open and close yourself, now there was Academy Boulevard, paved and leading to a gate that was guarded like it was the checkpoint between East and West Berlin. Inside, the Academy had its own post office, commissary, and telephone exchange. And the glistening new structures of the Academy itself were modernist masterpieces—sleek glass boxes designed by the largest architectural firm in the nation, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, rising up from the clay of the West, announcing the dawn of a new American era.

Don could be a part of that future, just as he’d always hoped. At his previous posting, in northern California, he had worked nights at Stanford to earn a master’s degree in political science. Now he was back in Colorado to start a version of the academic life he’d longed for, joining the Academy faculty as an instructor.

The Air Force moved the family into one of a warren of one-story military family houses on the new campus. Theirs was on a hill, with a small patch of grass and a south-facing front door. Don and Mimi set up four bunk beds in the basement level for their eight boys. That worked well until their ninth boy, Matthew, was born in December. Their oldest, Donald, was thirteen now, and he and the brothers close to him in age used the Academy grounds as a playground. They had the run of the place: the indoor and outdoor rec centers, the ice rinks, the swimming pools, the gyms, the bowling alley, even the golf course. No one held them back. In a time of feverish conformity, at the Academy there was also a sense of liberty—the Western frontier spirit, perhaps, or the optimism of a new generation, home from war, building an institution that faced the future with a serene confidence.

Don was like many of the teachers there: World War II veteran hero scholars, young and brash and erudite—and more open-minded than their counterparts at West Point or Annapolis, creating programs in philosophy and ethics that would have seemed out of place at an older, stuffier military college. His life plan firmly back in place, Don walked the Academy grounds with a certain infectious self-assurance. This was a return of the smooth and seamless Don of his high school president days—and those years in the Navy, playing tennis with the captain of the USS

Juneau

.

There had been a few years in between, it’s true, when it didn’t seem like things would go Don’s way. In his time away from Colorado, Don had hated his assignment in Canada seemingly out of proportion to what the situation seemed to warrant. As a briefing officer, he dealt with classified information, and he spoke in alarmed tones to Mimi about how lax the standards were there; to see papers tossed around without much care seemed to set Don off in a way that Mimi had not seen in him before. His emotional state was fragile enough to force him to take sick leave, first at a hospital at Sampson Air Force Base in New York, and then briefly at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C. It seemed to Mimi that Don had had an attack of nerves, not unlike what a lot of veterans of the war had, particularly ones like Don who never talked about anything they experienced in battle. But his next posting, in California, was better; Stanford was near his base, allowing him to do graduate work. And now that he was back in Colorado, he, like many of the men in his generation, had come to trust that if you did all the right things in all the right ways, then good things would come to you.

A year before the Academy had even opened, Don had written to the commander in charge of the Academy’s organization and construction, General Hubert Harmon, to propose that the Air Force adopt the falcon as its mascot—the same way the Army had its mule and the Navy its goat. Don had not been the only one writing the Air Force to suggest a mascot—the Academy’s archives have a folder filled with letters from interested citizens, recommending everything from the Airedale (pun intended) to the peacock—but he was the first to suggest the falcon, something he and Mimi would always point to, once the Air Force took up the idea, as a lasting accomplishment, their contribution to American military history.

The Galvins had brought a few birds along with them on their postings in Canada and California, jamming them in cages in the back of their Dodge woody station wagon everywhere they went. Now that Don finally was part of the Academy, he took over the falconry program, throwing himself into the job like a religious calling. He wrote collectors around the world to build the Academy’s stock of birds—accepting two falcons as gifts from King Saud of Saudi Arabia, working to score a few falcons from Japan, and writing the state of Maryland to ask permission to trap falcons there. His cadets flew them in front of tens of thousands of people in stadiums around the country—from Miami University to the Los Angeles Coliseum (in the rain), with a national television appearance during the Cotton Bowl in Dallas in between. He and his birds made it into the pages of

The

Denver Post

and

Rocky Mountain News

more than once, and he practically had a standing feature in the Colorado Springs

Gazette.

The birds came home, too. The whole family played a part in training Frederica, a goshawk Don got as his end of a three-way swap with collectors in Germany and Saudi Arabia. When she wasn’t scratching the children, Frederica sat on a perch in the front yard, in full view of the neighborhood and well within the sightline of a neighboring Alaskan husky. Once, the bird, which was not tethered, pounced on the dog. The husky ran away with a talon embedded in its fur.

Everybody came to know the Galvins—such a large family, and with their father, the captain who knew everything about falcons. Young Donald became the bird dog for his dad—his “very able assistant,” Don wrote in

Hawk Chalk,

the newsletter of the North American Falconers Association, which Don had a hand in founding—running ahead and kicking up the rabbits before his father let the birds go. If some failed to return, Donald and a few more of the older boys—John, Jim, and Brian—would wake up at five o’clock to help find them, listening for the bells that had been fastened to their legs for moments like this. From their little house on the hill, the smaller boys sometimes could spot their older brothers and their father through binoculars, climbing up a mountain or rappelling down a cliff.

Don and Atholl

At home, Don basked in the paterfamilias role while Mimi handled the details. Falconry, again, was helpful to him in this way: Not only did it engage him intellectually, it also allowed him to excuse himself from activities he would just as soon not involve himself in. He had long since taken to referring to the boys as numbers. (“Number Six, come here!” he’d yell to Richard.) When Don started taking night classes at the University of Colorado for a PhD in political science, something had to give. Rather than step away from his duties as the Academy’s falconry supervisor, Don gave up the one activity that was centered around the children: coaching his sons’ sports teams. He had become, as Mimi described him, “an armchair father.”

As the boys grew, their parents’ lives only became busier. There was never enough money or time, but the right attitude counted for something, and both he and Mimi continued to believe they had a family others hoped to emulate. Each Galvin boy served as an altar boy. One was responsible for serving a mass each day of the week. Their old friend Father Freudenstein remained in their lives, although he had moved on from Colorado Springs and now served three different parishes out on the prairie. This was not exactly a promotion for Freudy; most priests want to move to larger and larger parishes. But he continued to offer spiritual counsel to Mimi, and he became a favorite of some of the Galvin boys—known for conducting masses in record time, performing his old magic tricks, and showing the older boys the train set and slot machine he kept in the basement of his house, east of Denver. A devoted smoker and unrepentant drinker, Freudy once lost his driver’s license, and the oldest son, Donald, when he was in high school, spent a week out on the prairie, staying with Freudy and working as the priest’s chauffeur.

In these years, Don saw the boys only insomuch as they were helping out with the falcons. With Don working or away much of the time, Mimi maintained the home, keeping to a strict routine. She went grocery shopping twice a week, each time bringing home twenty half gallons of milk, five boxes of cereal, and four loaves of bread. More than once, she simply threw out toys that had been left lying around the house. Each morning, she bounced quarters off the boys’ beds. Each evening, she made dinner for eleven—iceberg lettuce, cucumbers, carrots, and tomatoes for the salad; minute steaks with a little salt and pepper; a bag of peeled potatoes made into mashers. When he was home, Don would set up four or five chessboards after dinner, line up a few of the boys, and play all of them at once. School nights were for homework and piano practice, not going out. Late at night, Mimi would wash and fold diapers.

In 1959, Don attended a Mardi Gras party in the Crystal Ballroom of Colorado Springs’ posh Broadmoor Hotel with a turban on his head and a live, short-winged goshawk in his left hand. He told everyone he was dressed as an ancient seer or mystic. That got his picture in the paper.

Mimi smiled alongside him. She had her own notoriety, thanks to the children. The

Rocky Mountain News

published Mimi’s recipe for lamb curry, seasoned with onion and apple and garlic and served with boiled rice and green beans, slivered almonds and artichoke hearts. The headline:

SHE SERVES EXOTIC FOODS TO FAMILY OF NINE BOYS

.

WHEN HE WASN’T

parachuting out of C-47s with the Air Explorer Scouts or studying classical guitar or practicing judo or playing hockey or rappelling down cliffs with his father, the Galvins’ oldest son, Donald, was a track star and all-state guard and tackle on the Air Academy High School football team—number 77. Going to his games was often the big family outing of the week. In his senior year, Donald took state in his weight class in wrestling, his team took the state title in football, and he was dating a cheerleader whose father happened to be his father’s boss, the Air Force general in charge of the Academy. Donald was, by many measures, his father’s son—handsome, athletic, popular—and to his brothers he was a hard act to follow.

He was also, in ways that Don and Mimi either missed or chose to overlook, not precisely what they assumed him to be. Donald was quieter than Don had been in high school, and despite everything he did on the ball fields he was not the sort of person who got elected class president. His grades were average, eventually earning him a spot at Colorado State, not the more selective University of Colorado. And while he looked the part of his father, the carefree charmer, he lacked the charisma to pull it off. From the time he was a teenager, it was as if there was something keeping Donald from connecting with the world in a conventional way. He seemed most at home, at ease with himself, climbing and rappelling from cliffs and raiding aeries in the great outdoors. But whatever sense of mastery Donald demonstrated out in nature didn’t play as well around people.

At home, Donald exercised supreme authority over his younger brothers—first as a sort of substitute parent, and then as something less wholesome. When his parents weren’t around, he became, by turns, a mischief-maker, a bully, and an instigator of chaos. It would start out innocently enough, before escalating in ways that some of his brothers found terrifying. Don and Mimi would go out—Don training with the falconry cadets, or picking up an extra class to teach at one of the local colleges, or studying for his PhD; Mimi volunteering with the opera—and Donald, the oldest, would have to baby-sit, which he would not want to do. To divert himself, he’d goof around with his brothers: “Open your mouth, and close your eyes, and I’ll give you a big surprise,” followed by a mouthful of whipped cream.