Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel (39 page)

Read Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel Online

Authors: Thaisa Frank

Moments later, she was surprised that the cobblestone street looked the same. She walked to the main room, where Parvis Nafissian was working with some fabric. Years ago he’d apprenticed as a tailor with his father in Turkey, and sometimes it amused him to make clothes for people in the Compound. When Elie came in, he held up a lace bodice.

Perfect for Gitka, she said.

Our siren, said Nafissian.

No one took notice of their conversation. Nor did anyone notice when Elie sat at the school desk, writing once again in the dark red notebook. She wrote quickly, filling one page, then another, as if she didn’t write fast enough the words would fly into the air. When she’d finished, she went upstairs and put the notebook in Lodenstein’s trunk. He reached for her in sleep, and she got into bed, treasuring the careworn quilt, the sliver of forest—pine boughs on each edge of the blackout curtains. She could feel Lodenstein’s strength. She could feel every bone in his body. And when he woke up and they made love, everything that happened in the forest disappeared. She recognized her own face only by the way he touched it—brushing her eyelids, tracing her mouth, caressing the curve of her cheekbones. She recognized the room only by the feel of his body. No lovemaking could be deep enough. She could not find him enough, could not touch him enough, could not kiss him enough. They had always been part of something larger than the war—something timeless, secret, unrecorded.

He drifted to sleep holding her—a deep sleep, far away from her. The quilt felt soft when Elie untangled herself. She stood near the door for a long time watching him.

Lodenstein woke a few hours later in an empty bed, threw on his trench coat, and went outside. It was dawn, and sun fell in shafts through the pines. He looked for Elie in the vegetable garden and saw fresh tracks on the grass. Her jeep was gone.

He went down the incline and rattled the diamond grating of the mineshaft, as if that would make it move faster. A few Scribes were making their way to the kitchen, rubbing their eyes. He heard someone mention the lottery, then the strike of a match for the first cigarette of the day.

He went to the kitchen: Elie wasn’t there. Maria, in a moment of being only sixteen, put her head on his shoulder and said she’d had bad dreams. He patted her and went to the main room of the Compound. No sign of Elie. He opened the door to Mueller’s old room. She wasn’t there either.

He knocked on the storage room. Asher answered.

Have you seen Elie?

Asher shook his head.

Her jeep isn’t here, said Lodenstein.

Just then Talia Solomon came rushing from the main room of the Compound.

Dimitri’s gone, she said.

His eyes met Asher’s. Both shrewd, both blue, both like Elie’s. Did this random resemblance bring her into the room? For a moment Lodenstein thought it did.

He went back to the main room, opened the top drawer of Elie’s desk and saw a note that said

To Gerhardt

. He put it in his pocket and went upstairs, racing past their room on the incline.

To Gerhardt

. He put it in his pocket and went upstairs, racing past their room on the incline.

The late summer had begun to turn cold. Pine trees shook with the wind as if simple people lived in the shepherd’s hut and an ordinary day without the war was starting. Once Lodenstein believed that the mind and the weather worked in tandem, but he’d come to realize that the weather was oblivious to everything. It shone and rained on atrocities and kindnesses, stinginess, violence, and generosity. It showed up for wars, weddings, peace treaties, and betrayals. For a moment he felt jealous of the weather because Elie would always feel its heat, its snow, its rain. Indeed, she must be somewhere now, feeling the violent wind.

He had never known this place without Elie. She’d driven him on the narrow road, shown him the forest, the shepherd’s hut, taken him into the earth, and introduced him to the Scribes. She’d explained the mechanical workings of the sun and the architect’s dream about the street and the city park. He’d never seen this place without sensing her presence—even when they were fighting, or she was on a foray. Now he looked at the forest alone for the very first time. It was blank, without dimension—not a forest, but a collection of trees. The feverfew waved in random clusters. The clearing where Elie parked her jeep reverberated with absence. He looked at the tracks of her tires and realized he would never again rush out late at night to make sure she was safe. And he would never wait for her to come back from a foray.

A few months ago, Lodenstein had taken another photograph of Elie in the clearing, which he always kept with him. Her hair was drawn back in a red bow, and she wore a white silk blouse with a white velvet rose pinned to the collar. He looked at it and felt her next to him. Everything about her came back to him—her delicate bones, her tea-rose perfume, the way she brought the entire world to the Compound.

Elie, he said, as if her name would invoke her presence.

THE TRUNK

Dearest Gerhardt,I know my actions have brought tremendous harm to the Compound. It’s hard to believe this happened because of a simple pair of glasses. I thought I’d be able to handle everything. But I couldn’t. I wasn’t even sure I’d be able to leave. But Dimitri is in danger—and I need to save as many people as I can. I hope you will understand. You must make sure that Asher and Daniel don’t go out anymore and that they have a clear passage to the room in the tunnel. There is extra flour hidden in the right-hand cupboard of the kitchen and five tins of ham in a crate underneath the sink. It’s not very much, but I hope it will last.I can’t begin to tell you how much I love you. I can’t begin to tell you how much I’ve thought about what you did for me, for all of us, and how you stood by me even when I brought unspeakable risk to this place. I know we both agreed to be nearly invisible for the sake of other people. I also know you did this much better than I did.I wonder what people will think of the Compound after the war, and whether they’ll remember us at all. I wonder if people will ever visit the cobblestone street piled with crates and the kitchen where La Toya made soup and the Solomons’ house where Dimitri played with Mufti. Or maybe this place will be forgotten. How strange if no one ever knows about the room where so many people played word games and slept and cried out. How strange if no one ever sees the sun rise on pulleys or the fake stars that shone on Hitler’s birthday. And how sad if no one remembers

Dreamatoria

.Please keep everyone here safe for me. And please hold them close, as I will hold them close, as I will hold you close.Love always, Elie Kowaleski

Elie left eight months before the fall of Berlin. A week after Berlin fell, the Scribes smelled smoke and worried that fire would reach the forest. Only Asher and Daniel weren’t worried. They’d both seen death up close.

But the forest around the Compound never caught fire. And a month after Berlin surrendered, Gerhardt Lodenstein guided the Scribes down the long tunnel, past the room with the bones, eleven kilometers in the dark next to the rushing stream, until they climbed into the sunlight of a northern town. Emaciated women cleaning the streets, not sure if their part of Germany had surrendered to the Russians, looked in amazement as almost sixty people in fur coats, many of them wearing glasses, emerged from a hole in the ground. They also saw an enormous trunk, followed by a wheelbarrow. Last to come up was a tall pale man in a trench coat.

Before they left the Compound, Lodenstein asked each Scribe to put a memento in the trunk. The ceremony was done with impatience and indulgence. The Scribes had spent nearly eight months with almost no food, but Lodenstein risked his life to drive to town for the few rations they had and never wavered in his protection.

Into the trunk, Sonia Markova put a red glove. La Toya, two cigarette holders. Gitka, a fur coat. Mikhail Solomon, his chess set. Talia Solomon, a Tiffany lamp. Nafissian, a dictionary for

Dreamatoria

. Some tore a page from a coded diary. Asher put in his blue and white coffee mug. And Lodenstein added them all, right next to the pair of Heidegger’s glasses.

Dreamatoria

. Some tore a page from a coded diary. Asher put in his blue and white coffee mug. And Lodenstein added them all, right next to the pair of Heidegger’s glasses.

Now the trunk stood before them like a living thing, as if it were waiting for a chance to speak. No one wanted it, and no one could say so out of respect for Lodenstein. All they wanted was to leave the Compound for good—to walk on real streets and travel to places far beyond this town. They wanted to see if they still had families. They wanted to see if they still had houses.

Lodenstein gave the trunk to Daniel because he was the youngest.

Keep it, he said. Keep it safe.

Daniel nodded. He and Asher took the trunk, which was still on the wheelbarrow. The Scribes hugged, kissed, and gave each other addresses of houses that might not be standing. And Maria and the Solomons had an altercation—the first one anyone ever heard—because Maria wanted to leave with Daniel.

Absolutely not, said Mikhail. You belong with us.

Lodenstein watched Daniel and Maria hug and kiss and cry. Asher and Mikhail exchanged five addresses so the two could write. He watched Gitka and La Toya disappear with their cigarette holders. And Sophie Nachtgarten walk away, carrying Mufti. Indeed, he watched every Scribe leave him, feeling more and more bereft. For so long his focus was on protecting them, feeding them, keeping them safe. Now he knew he would begin a long search for Elie. There were so many Kowaleskis in the world, and so many hadn’t gone back to Poland because Poland had as many bad dreams as Germany.

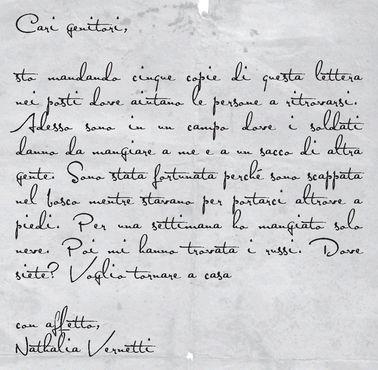

Dear Mother and Father,I am sending five copies of this letter to places that help people find each other. I am in a camp now where soldiers are feeding me and a lot of other people. I was lucky because I ran into the woods when they began to march us away. For a week all I had to eat was snow. And then the Russians found me. Where are you? I want to go home.Love,Nathalia Vernetti

Other books

She's Having a Baby by Marie Ferrarella

Merv by Merv Griffin

A Dangerous Nativity by Caroline Warfield

Big Superhero Action by Embrack, Raymond

No Escape by Heather Lowell

Levels of Life by Julian Barnes

Alien Bounty by William C. Dietz

In This Hospitable Land by Lynmar Brock, Jr.

The Barbary Pirates by William Dietrich

Dirty Country Love: A Step-Brother Romance Novella by Quinn, Candy