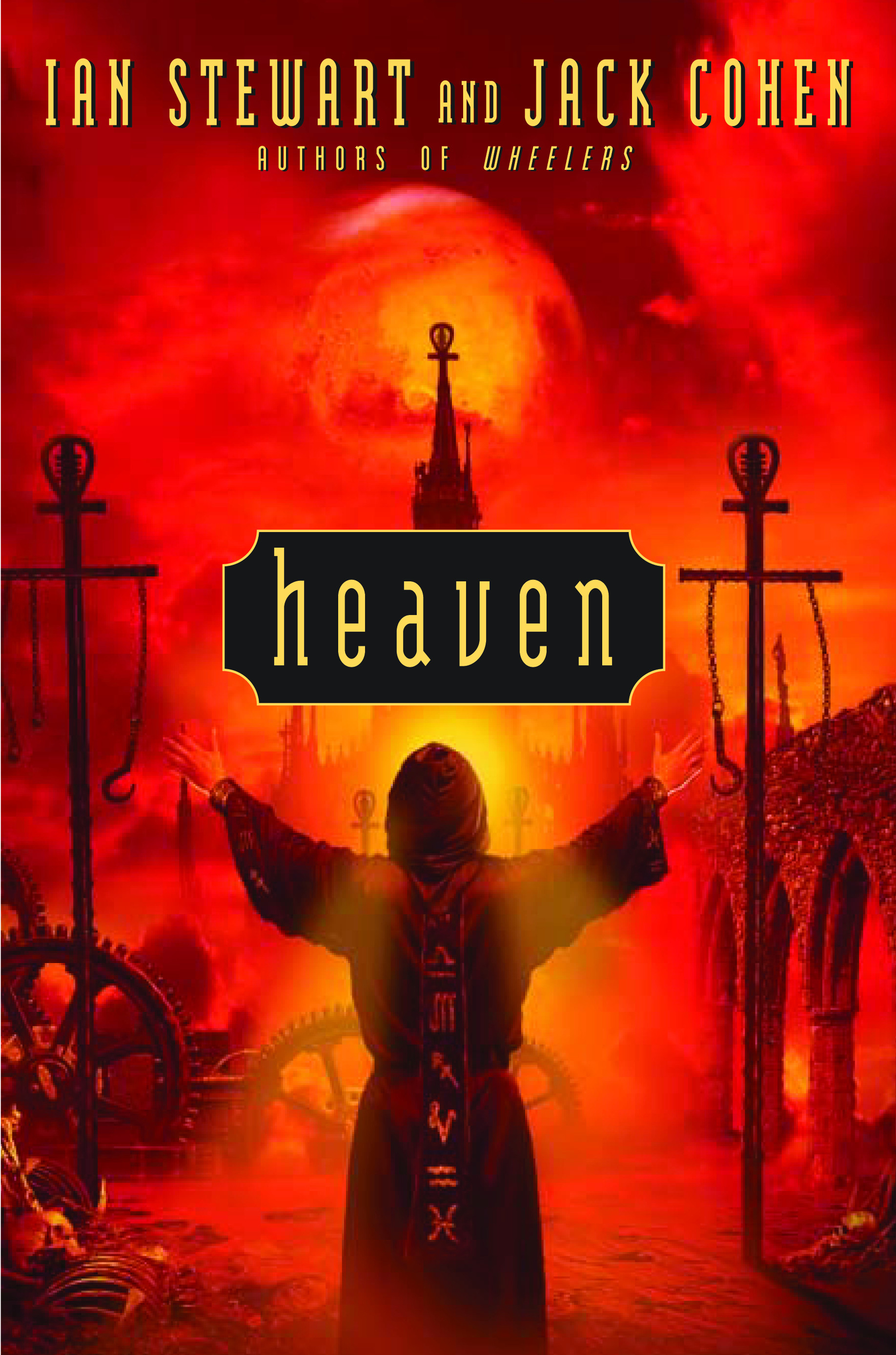

Heaven

Authors: Ian Stewart

Copyright © 2004 by Joat Enterprises & Jack Cohen

All rights reserved.

Aspect

Warner Books

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

Aspect® name and logo are registered trademarks of Warner Books.

First eBook Edition: May 2004

ISBN: 978-0-446-56091-7

By Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen

Fiction

WHEELERS

Nonfiction

THE COLLAPSE OF CHAOS

FIGMENTS OF REALITY

THE SCIENCE OF DISCWORLD (WITH TERRY PRATCHETT)

THE SCIENCE OF DISCWORLD II: THE GLOBE

(WITH TERRY PRATCHETT)

WHAT DOES A MARTIAN LOOK LIKE?

Nonfiction by Ian Stewart

CONCEPTS OF MODERN MATHEMATICS

GAME, SET, AND MATH

THE PROBLEMS OF MATHEMATICS

DOES GOD PLAY DICE?

ANOTHER FINE MATH YOU’VE GOT ME INTO

FEARFUL SYMMETRY

NATURE’S NUMBERS

FROM HERE TO INFINITY

THE MAGICAL MAZE

LIFE’S OTHER SECRET

WHAT SHAPE IS A SNOWFLAKE?

FLATTERLAND

THE ANNOTATED FLATLAND

Nonfiction by Jack Cohen

LIVING EMBRYOS

REPRODUCTION

PARENTS MAKING PARENTS

SPERMS, ANTIBODIES AND INFERTILITY

THE PRIVILEGED APE

Contents

Everything that man seeks in the world: someone to bow down before, someone to entrust one’s conscience to, and a way of at

last uniting everyone into an undisputed, general and consensual ant-heap, for the need of universal union is the third and

final torment of human beings.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky,

The Brothers Karamazov

The order that emerges in enormous, randomly assembled, interlinked networks of binary variables is almost certainly the harbinger

of similar emergent order in whole varieties of complex systems. We may be finding new foundations for the order that graces

the living world. If so, what a change in our view of life and our place must await us.

Stuart Kauffman,

At Home in the Universe

Memeplexes are groups of memes that come together for mutual advantage. Once they have got together, they form a self-organizing,

self-protecting structure that welcomes and protects other memes that are compatible with the group, and repels memes that

are not.

Susan Blackmore,

The Meme Machine

NO-MOON

Identifying with other creatures’ feelings is only one part of the problem. The more important question is, how can you make

effective use of your knowledge of what they are feeling? Emotions are straightforward. Motives—those are quite another matter.

And without an understanding of motives, there is no true empathy, no predictability, and no power.

Archives of Moish

T

he lion-headed Neanderthal woman sat at the end of the pier, dangling her feet in the sea to cool them . . . but her mind

was elsewhere. Usually, she was composed and carefree, but today she was troubled by an apprehension to which she could not

put a name.

She shook her thick mane, trying to clear her head. It was a beautiful day on a beautiful planet, and everything was right

with the world.

For a few moments, she almost believed it.

Small wormlike animals circled around her toes, occasionally probing her skin with thin tubes, only to withdraw as soon as

they sensed alien biochemistry. There was no nourishment here, and the ancient evolutionary bargains were null and void. Newcomers

arrived, made the same mistake, and retreated in their turn, baffled. The woman laughed, a gravel-throated chuckle: The worms

tickled, and she liked that.

Her trading name was Smiling Teeth May Bite. Her friends called her May. Her enemies could call her what they wished. To both,

throughout the Galaxy, she and her kind were “lion-headed”—not literally, but because their ocher skins, their flamboyant

sunbursts of marmalade hair, and their wide noses gave them a decidedly leonine appearance. In May’s case, the effect was

enhanced by tawny eyes and a tendency to snarl.

She wore a short olive green tunic, cut diagonally to leave her left shoulder bare. Several small packages were arrayed around

her waist, as if hung on a belt, but with no visible means of attachment. Precursor technology, like most inexplicable things

in the Galaxy.

A pair of hand-woven sandals, which she had picked up the previous year on Nothing Ventured, lay next to her at the pier’s

edge.

She was waiting for a sail. Not any sail, but a particular one: lateen-rigged in a motley patchwork of colors, torn and repaired

many times. She redirected her gaze from the swarming worms to the haze where sea met sky. The motion was graceful and haughty.

There was an economy to her movements that made her powerful frame seem always perfectly balanced. She sniffed the air laden

with the characteristic smells of rotting algae and salt dust; her eyes flicked to left and right, instinctively noting every

movement.

She could see a few sails on the horizon, and more of them closer to the port, but none were the sail she was waiting for.

Despite her uneasiness, she laughed again, this time in amusement. Second-Best Sailor was late. As he had been last year,

and the year before, and would be next year. The reason was always the same. His route would take him along at least three

foreign coasts and through several of the innumerable archipelagos that infested No-Moon’s world-girdling ocean. At some point

of his voyage he would be distracted by the dubious attractions of one of the more exotic ports, find himself behind schedule,

and try to invent a shortcut to catch up. Then, entirely predictably, he would be thrown off course by the Change Winds.

May knew this, and she also knew why he was called Second-Best Sailor, and that meant that there was no point in trying to

make him see sense. So, as she did every season, she had left extra time in her schedule for him to find his way into port

from wherever his latest episode of irresponsibility had led him. He would turn up soon . . . unless his boat had sunk. But

he was Second-Best Sailor, not Thousandth-Best. He would never allow his boat to sink.

She didn’t mind waiting. She liked the port and the natural sea breezes, just as she liked being immune to the depredations

of the carnivorous worms. It made sense to hang around for a few more days until Second-Best Sailor turned up. The trading

would surely be up to expectations.

Would it not?

A foot scuffed the timbers of the pier, and without turning her head May knew that her companion had returned from her foray

into the maze of narrow floating walkways that constituted the above-water part of Isthmus Port.

“I have reregistered our credentials with the Trade Authority like you told me,” the newcomer said. Her voice was in a slightly

higher register than May’s, but her orange mane was just as luxuriant and her nose was, if anything, even more like a lion’s.

Her eyes were an improbable royal blue, exactly the same color as a species of electric eel on one of the hubworlds where

Neanderthals often traded. The coincidence had given rise to her trading name of Eyes That Stun the Unwary—usually abbreviated

to “Stun.”

Her tunic was a deep, dusty purple. She was accompanied by a fat, goatlike creature on a braided lead. A yullé—clever but

not sentient. The animals were bred in a variety of shapes and colors, and this one had a dramatic pattern of large and small

spots, black on gray.

There were many Neanderthals in the ports of No-Moon, and following habits laid down thousands of generations ago, most of

them kept pets. Over the centuries, their unique empathic sense had allowed them to tame several dozen species, from as many

worlds. May, a rare exception, didn’t keep any pets on No-Moon—land animals occasionally upset the customers. But back on

board Ship, she had quite a menagerie.

“It went as I expected,” said May. It wasn’t a question: The Neanderthals had an innate ability to sense one another’s emotional

flow-patterns, and those of most other creatures. It was why they had been prized as Beastmasters, back before the Rescue,

116 generations ago.

“The permission fee was adequate, as you foresaw,” said Stun. May snorted. Even a flatface would have been able to appreciate

that a small increase on last year’s fee would be acceptable. And Stun had been given latitude to offer quite a bit more than

that if previous custom no longer applied.

Stun bobbed her head in affirmation, and her mane rippled. She joined May on the edge of the pier. The worms quickly discovered

this new target for their affections, and were equally disappointed by it.

“The Change Winds must’ve started early,” Second-Best Sailor protested. “Not my fault. Nothin’ anyone could’ve done to see

that

comin’, ain’t I right, boys?”

He had been publicly congratulating himself on weathering the storm without inflicting too much damage on the boat, when Short

Apprentice had noticed that the stern thole-boards had come loose and were trailing behind, with a danger that their staylines

might get tangled in the steering gear. Then, when Short Apprentice had been dispatched through a sallyport to secure the

thole-boards temporarily to the planking-rail, Fat Apprentice had cast doubt upon the wisdom of their three-day stopover in

Coldcoast Docks, and Second-Best Sailor had felt obliged to defend his judgment. Even the reefwives, he pointed out, found

the vagaries of the weather difficult to fathom, so he could scarcely be blamed for the freak storm that had come from nowhere

and driven them many miles from their intended course.

Fat Apprentice didn’t argue. He didn’t point out that although the precise timing of the Change Winds was unpredictable, their

occurrence around that time of year was entirely to be expected. He did not point out the obvious, because he had no wish

to be sent out to join his fellow crew member in the heaving turbulence of the ocean roof. It could make you airsick. Fat

Apprentice had cultivated a deceptive air of somnolence and absentmindedness, but behind that facade he was surprisingly intelligent.

He just hadn’t had much of an education. He was smart enough to hide just how smart he really was. Sailors didn’t go much

for smarts.

As he looked around the underwater cabins where he and his crew lived and worked, Second-Best Sailor consoled himself that

below the ocean roofline his vessel was pretty much intact—save for those annoying stern thole-boards, which must have been

inadequately tensioned when their staylines were being storm-lashed.

’Bovedecks, well, that was another matter entirely. No marine creature was ever completely at home out of the water, and Second-Best

Sailor was no exception. But he had to find out how much damage the boat had sustained above the roofline, and that meant

putting on his sailor suit and going ’bovedecks to inspect the garden, which had been at the mercy of surges for the better

part of a week. Right now he was in no hurry to do that. He

knew

that there would be squids in the lemon trees again, and most likely crabs in the sagegrass as well. Those things always

happened when the boat was exposed to a gale-strength airstorm.

It had been the worst storm he could remember. For several days he had been at the helm, relieved only for a few short rest

breaks, trying to control the heavy boat as it pitched and yawed its way through outrageous waves. The constant rush of aerated

water past the hull hurt his siphons and made him feel sick. The boat had tossed in the crushing surges, creaking and shuddering

as if it was about to fall apart entirely.

It had been bedlam. His apprentices had no sooner tied down an errant hunting net than half a ton of cargo had torn loose

from its mountings. And as soon as they had improvised secure fastenings for the cargo, the steering gear had seized up and

had to be freed with pry bars and massive applications of boiled blubber lubricant. And all the while, the waves and the wind

jerked the boat in so many directions that he was sure some of them didn’t exist. Second-Best Sailor had very nearly been

sucked out of the helm cabin into the surrounding ocean at least a dozen times by surging pressure-waves, and his tentacles

were bruised and sore from trying to hold on to safety handles, furniture—anything that was solidly bolted down. Short Apprentice

had very nearly been washed out through a broken sallyport. If he had not grabbed hold of Fat Apprentice at the last moment,

they would have been down to one crew member, and Short Apprentice would have been faced with a long swim to rendezvous at

their next destination.