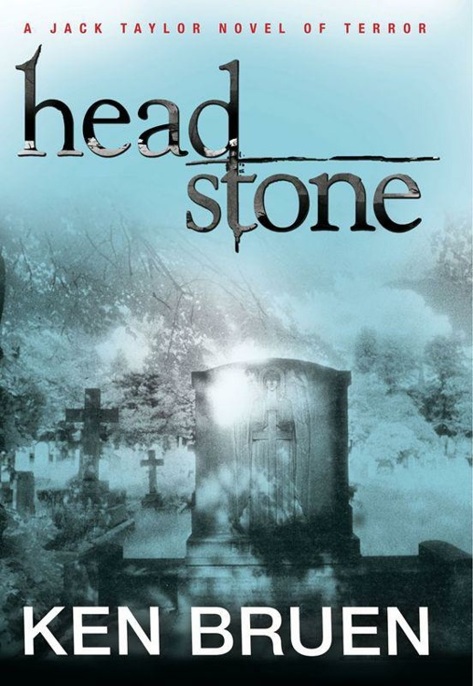

Headstone (25 page)

Authors: Ken Bruen

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Thrillers, #Crime

awesome sight than the Atlantic at full roar. You

up for that?”

Poking his pride.

He put the car in gear and we were speeding out of

there. His face was stone. As we came off the

Grattan Road, I saw the off - license I was heavily

dependent on still being there, said,

“Kosta, stop a moment. Let’s get some fortification

for the wind.” He pulled over, began to get out,

asked,

“Jameson?”

“Perfect and oh . . .”

Like I’d just thought of it,

“A pack of Gitanes.”

I didn’t want them but I desperately wanted to buy

time and prayed the assistant would have to go

looking for such a brand, or at least explain why

they didn’t have it. I only needed minutes.

Four minutes and he was back, tossed a pack of

Marlboro, said,

“No Gitanes.”

The bottle of Jameson felt heavy as he handed it

over. He glared at the sea, said,

“It’s getting worse.”

He had no idea.

I said,

“Something you’ll never forget.”

That clinched it.

He parked near the tower, the silhouette of the

diving boards barely visible in the driving rain. I

said,

“See, under the tower, a shed. We can get

protection there. When we were kids, we used to

huddle under there, watch the sea roar.” If kids had

done it, how could he baulk? He sighed, reached in

the glove department, took out the Glock, said,

“Force of habit.”

We made our way down along the side, the wind

tugging like the worst kind of religion. Once inside

the shed, we caught our breath, I unscrewed the

Jay, handed the bottle over, said,

“This will warm you.”

He took a deep draw, handed it back, and I toasted,

“Long life.”

I used the Zippo to fire us up and he put the Glock

on his knee, the charade at an end. He took but one

long fervent draw on the cigarette and flicked it

into the storm, asked,

“What’s up Jack?”

I said,

“I met your daughter.”

He was stunned, muttered,

“What?”

“Actually, she found me. Told me that Edward had

many faults but molestation wasn’t one of them.

She did say that he was chipping away at your

business and you’d never allow that.”

He grabbed the bottle, drank, said,

“Poor girl, she’s deluded.”

I let that sit, then,

“I checked around and, sure enough, he was no

prince but he wasn’t what you said and he was

most definitely a rival to your business.”

He had the Glock in his hand, said,

“Spit it out Jack.”

I did.

“You used me to erase him. That a friend of mine

got killed was just friendly fire. Primarily, you got

rid of a son-in-law you loathed.”

He stood up, watching the wild sea, said,

“Ah, Jack, why couldn’t you just let it go?”

Leveled the gun at me, said,

“I liked you, Jack, I really did.”

Pulled the trigger three times and was bewildered,

hitting on empty. Now I stood, shucked the

Mossberg free, said,

“I never wanted Gitanes, I just wanted time to,

shall we say, defuse you.”

I racked the pump. He had to shout over the

growing tempest, said,

“Jack, you’re not going to do this. You owe me. I

got rid of the priest and his playgirl housekeeper.”

I was taken aback but didn’t lower the Mossberg.

Gasped,

“Gabriel?”

He nodded, control sneaking back, said,

“See? I have your back, my friend. The priest was

very cooperative; emptied all the bank accounts,

too.”

Trying to keep my shock in check, I asked,

“He’s dead?”

He waved a dismissive hand at the sky, said,

“He’s in the wind.”

Then added,

“Which shows my friendship for you is real.”

I laughed, said,

“I love it, especially as you just attempted to

unload a Glock into my face.”

I ordered,

“Give me the car keys.”

He did, his eyes darting round for an opening. I

backed away, out of the shed. He asked,

“How do I get home without transport?”

I didn’t look back as I climbed along the railing,

said,

“Join Gabriel, go in the wind.”

The sacred and profane

Clancy, the Garda superintendent, had been

ominously absent during all of the Headstone

drama. Didn’t mean he didn’t know. How could he

not?

Ridge becoming a media darling—and he had to

know my hand was in there. Mason, his new pet PI,

taken off the board. Once my best friend, he hated

me with all the passion that once had bonded us.

The railway station where my dad had worked was

being revamped. The staff was being moved to a

new building in the wilderness close to the docks.

An Irish gulag. Did they have a say in this?

Right.

As homage to my father, I decided to take a last

look at the station before they moved to the barren

plains. I hoped I’d meet Brian Carpenter, for

decades the stationmaster, or Martin Quinn who,

even as mayor, continued his day job on the

railway. Now that’s class.

As I got to the station, the occupants of the Simon

Community were being sent out for the day, to kill

the time till they could return. One asked me

politely if I could spare a cig and I gave him the

packet. I moved onto the platform, could almost

feel my dad’s hand in mine as he showed me the

trains when I was little more than a toddler.

Engulfed in memories of him, I failed to notice the

burly figure come up behind me until he touched

my shoulder. A train was approaching and I still

wonder: if I hadn’t moved as fast, would the touch

have become a push?

I swirled round to face O’Brien, Clancy’s hatchet

man. We had bad history, mostly of violence and

hurleys. He was surprised at my sudden turn,

recovered, said,

“The Super would like a word.”

Not negotiable.

That much I knew from previous history. I

followed him out of the station, resisting the

temptation to look back. My dad was in my heart,

that was what counted. A sleek Mercedes was

outside, the engine humming, another thug at the

wheel. I got in the back, O’Brien following.

The five-minute journey to Mill Street and Garda

headquarters was swift and silent. I had nothing to

say to these hoodlums. We moved quickly into the

station and then Clancy’s domain/office.

He was sitting behind a new mahogany desk, as

vast as his ego. He seemed to have grown in girth

to match it. Dressed in full uniform, a riot of

insignia pinned on the tunic, he busied himself with

papers as O’Brien took up position behind him,

smirk in place. Finally he looked up, took off his

gold pince-nez, said,

“Ah, the fingerless Taylor.”

I said,

“Nice to see you too. Sir.”

He gave a predatory smile as he pulled up a very

old file, blew the dust dramatically off it, said,

“Jacko, Jack, you must be very proud, your dike

lady being promoted and your dope dealer friend

involved in the head shops.”

Stick it to him or not?

I stuck it, said,

“One does what little one can, as you know. The

little, I mean.”

O’Brien moved but Clancy waved a restraining

hand. He had better fodder than a wallop. Asked,

“You a fan of TV, Jacky boy?”

“Just TnaG, the Irish channel.”

He was delighted, said,

“I think even they show a very popular series titled

Cold Case

.

We, in our own small way, have been going

through old files, clear the debris of the past,

onwards and upwards to a new proud Irish

nation.”

I was lost.

He tapped the file, said,

“This is your old man. Now, I liked your father.

Such simple men seemed to be the very backbone

of our society then.” Seemed.

Very worrying. He continued,

“But I hate hypocrites and I detest thieves.”

I tried with all my might to rein it in. O’Brien

knew, waited till I moved and he’d beat me

senseless. Clancy continued,

“The files from the railway were fascinating, the

pension fund especially. Did you know your father

was in charge of it?”

I didn’t.

He was cruising, killing me, pushed for the home

run, said,

“He was a thief, stole from the very families he

was supposed to be looking out for. And you,

you’ve turned out just like him. He’d be very proud

of the drunken limping deaf disaster you’ve

become.”

Instinctively, I reached for the Walther in my

waistband and O’Brien’s face registered alarm,

knowing he couldn’t get to me in time. But no

weapon. Out of respect to my dad, I’d left it at

home. I let my hand show.

Empty.

Like the damn poem:

Empty of all

………………………But memories of you.

I managed to mutter,

“Anything else, sir?”

Clancy looked to O’Brien.

“The fuck was going on?”

They’d hit me every which way but loose and I

was . . . doing . . . nothing. O’Brien gave a cautious

shrug and Clancy said, less certain now,

“No. You can go but bear in mind, we’ll be

publicizing your father’s thievery.”

I managed to turn around, moved to the door,

stopped, said,

“My left hand still has its fingers.”

He was puzzled, asked,

“So?”

I lifted the middle finger, said,

“Cold case that.”

Reeling down the town, my mind on hyperdrive

from the revelations, I was stopped by a tinker

woman who said,

“Jack Taylor.”

I nodded and she asked,

“My poor mother, she’s dead three years now and I

can’t afford a headstone.”

I handed her my wallet, said,

“We can’t have that.”