Greece, the Hidden Centuries: Turkish Rule From the Fall of Constantinople to Greek Independence (37 page)

Authors: David Brewer

Tags: #History / Ancient

Guys’ work was one of the first to give a favourable account of the Greeks and to express confidence in their future. The Greeks of today, he wrote, are the men of all time, and his son, congratulating him on his book, wrote ‘The Greeks in your scenes are no longer in chains.’

20

18

Greeks Abroad

I

n the later years of Turkish rule in Greece it was mainly trade, by land or sea that took Greeks abroad. But in the earlier period there were many other reasons for Greeks to leave home, temporarily or permanently.

The earliest reason, as the Turks advanced through Byzantine territory, was simply flight. When Thessalonika was taken by the Turks in 1430 many of the Greek inhabitants fled to Venetian colonies, and there was an even greater and wider exodus when Constantinople fell in 1453. The consequent loss of Constantinople’s population, combined with losses during the siege, meant that Mehmed the Conqueror had to take drastic measures, combining compulsion with inducements, to repopulate Constantinople from other Turkish controlled regions. More Greek emigrations followed later Turkish conquests – of the Peloponnese in 1461, Trebizond on the Black Sea in 1461, Évia in 1470, and in the following century Rhodes in 1522 and Cyprus in 1571.

Greek refugees began to appear all over western Europe. In the years immediately after the fall of Constantinople they were listed in the town records of central France (Nevers), northern France (Amiens, Abbeville) and many towns in today’s Belgium such as Brussels, Bruges and Tournai. Greeks were also recorded in Germany and Spain, in England – especially London – and in Scotland. The records are particularly comprehensive for London and other parts of England because in 1440 the English government brought in a tax on alien residents that was known as the Alien Subsidy – a subsidy from the aliens rather than to them. The lists of those liable to the tax contain many who were certainly Greek and others who – the spelling of names, especially foreign ones, then being haphazard – were probably Greek.

However the main destination for Greek emigrants after the disaster of 1453 was the nearest point, Italy, for which the Adriatic port of Ragusa, modern Dubrovnik, was often the embarkation point. Venice was particularly welcoming. She had held parts of Greek territory, including Crete, since the Fourth Crusade of 1204. There were already many Greeks in Venice, and as early as 1271 they had been officially allowed to live there. In 1470 the Greeks in Venice were given permission to use a wing

of the Church of San Biagio for their services, and in 1514 to build their own church, which was finally completed 60 years later as San Giorgio dei Greci. By the late fifteenth century there were around 4,000 Greeks in Venice, and a century later even more, perhaps as many as 15,000.

Some Greeks left home only temporarily, with the specific purpose of raising money from fellow Christians to ransom members of their family who were being held captive by the Turks. One particularly energetic collector was Nikólaos Tarchaniótis, trying to ransom his parents, and between 1455 and 1459 he visited Milan, Lille, Brussels, Paris and other places in Italy and France on this mission. Nothing is known of him after 1459, so it seems that he raised the ransom money and that he returned to Constantinople.

Some Greeks got help in raising money through the system of ecclesiastical indulgences, which gave exemption from penances for confessed sins. A senior cleric would provide a letter granting such exemption to those who gave money or bequeathed it to one or more named Greek petitioners. The amount to be given (‘aliquod subsidium quod conscientia eorum dictaverit’

1

) was not specified; presumably it was up to the bearer of the letter to decide if it was enough. But the period of exemption was spelled out, and depended upon the seniority of the writer of the letter: 40 days from Archbishop Booth of York, a full year from Pope Pius II.

Many Greeks, however, settled permanently abroad, and needed some means of supporting themselves. For some, inherited wealth and aristocratic birth was enough. One such was Anna Notarás, daughter of Loukás Notarás, the commander-in-chief of the Byzantine forces defending Constantinople in 1453. She went to Venice shortly before Constantinople fell, was joined later by her brother Isaac, and lived in Venice until her death in 1507, reputedly at the age of over 100. She was rich enough to maintain other distinguished Greek exiles in her household, and to provide employment as servants for the less distinguished. Both categories were also helped by Cardinal Vissaríon in Rome. Vissaríon had been the leading Byzantine advocate of the union of the Catholic and Orthodox churches at the 1439 Council of Florence, after which he converted to Catholicism, became a cardinal and was twice considered for the papacy. He was a tireless rescuer of manuscripts of ancient Greek texts, and at his death left his entire library to Venice, seeing it as the most stable of the Italian states.

Other Greek exiles needed a skill to give them a livelihood. Some drew on their knowledge of the Greek language as teachers or copiers of manuscripts. Some were musicians – for example, Greek trumpeters at

Ragusa, and a Greek in France skilled on the lute and harp. An unusual skill was in the drawing of gold wire, and Greek gold wire drawers were recorded in London and France, and in Venice where in the early 1500s they formed one of the wealthiest sections of the Greek community. They prospered because the process had been developed in Byzantium but was little known in western Europe. It involved pulling gold rods through a diminishing series of funnel-shaped holes, each transmission reducing the thickness but increasing the tensile strength because the constituents of the metal were compressed. The resulting gold thread might either be used on its own or be wound round silk or other fibre. But the Greek gold wire drawers aroused local opposition and an enactment of 1463 in London barred alien practitioners from having shops in the city. Copying the procedure required little beyond some simple instruments and brute strength, so the skill passed from Greek emigrants to locals and this initial source of Greek prosperity did not last.

A skill less easily copied and so more reliable was the practice of medicine. The Greeks were far from being the only doctors practising in the countries of Europe, but their Byzantine background gave them two significant advantages. They could read the works of the ancient medical writers such as Hippocrates and Galen, and the summaries of these writings first compiled in the tenth century. Greek medical practice was therefore based on texts instead of oral tradition. Furthermore the standard of medicine as actually practised in the monastic and public hospitals of Constantinople was particularly high. Only in Italy, especially Venice and its dependencies, was comparable skill and practice to be found.

Perhaps the most remarkable career, in medicine and in other fields, was that of Thomas Frank, who was referred to as Thomas Frank, Master of Medicine or Magister Thomas, Physycian. He was a Greek from the Venetian possession of Koróni in the south-west Peloponnese, hence also the names Magister Thomas Greke and Thomas Coronaeus or de Coron. He was in London by 1436, when he applied for denizenship, that is permission for a foreigner to reside in the country with the rights of a citizen. Fortunately for Thomas a member of the council that heard and granted his application was Cardinal Henry Beaufort, bishop of Winchester. Beaufort became Thomas’ patron, and Thomas became Beaufort’s physician.

Thomas stayed in London, and his name appeared regularly on the Alien Subsidy lists from 1440, when they started, until 1447. He lived in the Broadstreet ward, which was also where the Italians of London tended to settle. Thomas was doctor to a prominent Genoan, had

commercial dealings with one wealthy Venetian and was executor of the will of another. In 1440 another opportunity to prosper came his way: he was appointed rector of the wealthy parish of Brightwell in Berkshire, an office that was in the gift of his patron Cardinal Beaufort.

Thomas was an absentee rector, simply drawing the rector’s income, and he appointed a curate to do the work. This was common practice at the time. What was somewhat unusual was that Thomas had not been ordained a priest, but Beaufort got permission from the Pope for Thomas to delay ordination, in effect indefinitely. However in 1447 Beaufort died and Thomas left England, though still apparently drawing the benefits of being rector of Brightwell. The Brightwell saga continued. Thomas’ curate also died, and the Pope ordered an inquiry because divine worship there was much diminished, the church was in ruins, and the cure of souls was not being exercised. This was an opportunity for the bishop of Salisbury, whose diocese included Brightwell, to claim the right to appoint Brightwell’s rector, taking this right away from the bishop of Winchester in whose gift it traditionally was. Winchester, whose then bishop, William Waynflete, later became Lord Chancellor of England, won the day.

Meanwhile Thomas had gone to France, and by 1451 was physician to the French King, Charles VII. He became a significant figure at the French court and in 1456 the Milanese ambassador reported to the Duke of Milan that ‘Master Thomas the Greek has as much influence with the king and the whole court as you have with me.’

2

In 1456 Thomas died of a stroke, and after his death the King was reported as being most pleased with what Thomas had done. Thus this exceptional man achieved a successful career in two foreign countries and in three different fields, as doctor, cleric at least nominally, and as courtier-diplomat, helped by what today would be called networking.

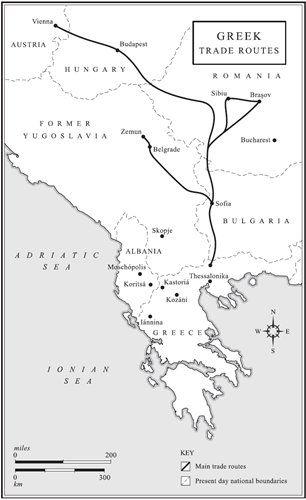

From around 1600 these early Greek emigrants were followed by others who were mainly traders. Overland the principal routes to the northern Balkans and beyond started from Thessalonika and diverged at Sofia, one road heading roughly westward to Belgrade, one northward to Budapest and Vienna, and one eastward to towns in today’s Romania. Consequently many of these adventurous merchants came from towns close to the northern border of today’s Greece – Iánnina, Kastoriá, Kozáni – or just beyond it, such as Koritsá (modern Korça) or Moschópolis (modern Pogradec).

The earliest official recognition of an expatriate Greek merchant community was in the Romanian towns of Sibiu and Brasov. In 1636, when

the area was still nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, the semi-autonomous ruler of Transylvania, Rakoczi I, gave permission for the Greeks to form a corporate association. In 1678, by which time the area was an Austrian possession, a similar association was formed at Brasov, and the two were later combined.

These associations were officially open to any foreigner – Bulgarians, Serbs and Jews as well as Greeks – but Greeks quickly came to dominate them. The first Sibiu body of 1636 had 24 members, of whom 17 were Greeks, and 30 years later almost all were Greeks. The association was governed by an elected council of twelve. In a ruling ahead of its time women could belong to the association, though they could not become

members of the council or vote for them. The association was limited to wholesale trade, so no retailing and no shops were allowed. The association collected state taxes from its members and in return its activities were protected. The behaviour of members was regulated. An association code of conduct of 1704 states that to avoid antagonising their hosts they must show respect to all government officials and the local population. They must also be polite to the association’s council members, and not, says the code, use expressions such as ‘Why are you ordering me about?’ or ‘Why should I?’

3

The association was therefore a combination of a guild with restrictions on trade, a corporate body with privileges, a tax collector and a foreign group with particular obligations.

The Greek merchants of Sibiu and Brasov handled a wide range of products imported from all over the eastern Mediterranean region. Textiles were prominent, either the raw materials (wool, cotton, silk), cloth (calico, damask) or finished garments (dresses, shawls, waterproof clothing). They also dealt in natural products (lemons, figs, rice, tobacco, and indigo for dyeing) and spices (pepper and nutmeg).

The other main concentrations of Greek expatriates were on the routes west or north via Belgrade and neighbouring Zemun on the Sava where it joins the Danube, and beyond Belgrade in Budapest and Vienna. In Zemun, besides merchants, there were Greeks practising crafts or trades as goldsmiths, silversmiths, furriers, bakers and shoemakers. One Greek set up a silk factory, another a brewery, and the Greeks were regarded as excellent innkeepers and restaurateurs. A mark of Greek involvement in the life of Zemun on the Sava was the election in 1803 of a Greek as mayor of the town.

In Budapest Greeks had been visitors since the early 1600s, bringing farm produce and homemade clothes to the local fairs. Later they prospered as merchants, and used the capital they accumulated first to rent farms and buildings and later to buy them. But it was in Vienna that Greek prosperity and influence was most marked. From trading the Greeks moved into banking, providing funds for many major enterprises. They became so prominent as financiers that the Greek association of merchants and bankers had to issue a denial that they were in business to charge interest: ‘We are here to practise trade, not usury.’

4

The leading Greek banker in Vienna was Símonas Sínas, merchant, owner of 30 villages in Austria and many buildings in Vienna and Budapest. He was one of the main contributors to the building of the Greek church in Vienna in 1803, was ennobled as baron by the Austrians, and his son Georgios provided five million florins for the construction of the suspension bridge over the Danube linking Buda with Pest.