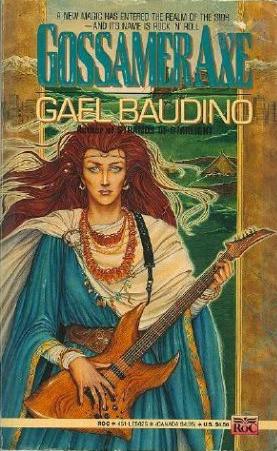

Gossamer Axe

Gael Baudino

An STM digital back-up edition 1.0

click for scan notes and proofing history

valid XHTML 1.0 strict

Contents

A ROC BOOK

ROC Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane,

London W8 5TZ, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood,

Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 2801 John Street,

Markham, Ontario, Canada L3R 1B

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road,

Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

First published by ROC, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc.

First Printing, August, 1990

Copyright © Gael Baudino, 1990 All rights reserved

“Don’t Tell Me You Love Me” by J. Blades. © 1982 On the Boardwalk Music (BMI). All rights controlled by Kid Bird Music. Used by permission. “Hollyann” by T. Schultz. © 1986 Hideaway Hits (ASCAP). Used by permission. All rights reserved.

“Metal Health” by C. Cavazo, K. DuBrow, F. Banali & T. Cavazo. © 1983 The Grand Pasha (BMI). Used by permission. All rights reserved.

ROC is a trademark of Penguin Books USA Inc. Printed in the United States of America

This book is dedicated to the memory of:

Genevieve Bergeron

Helene Colgan

Nathalie Croteau

Barbara Daigneault

Anne-Marie Edward

Maud Haviernick

Barbara Maria Klueznick

Maryse Laganiere

Maryse Leclair

Anne-Marie Lemay

Sonia Pelletier

Michele Richard

Annie Saint-Arneault

Annie Turcotte

You are loved. You are missed.

Sometimes, rock and roll dreams come true

. —Popular Mythology

Many people, knowing or unknowing, had a hand in this book, for it was the living of it that made the writing possible.

Shawn McNary taught me rock and roll and what volume controls were all about. Therese Schroppeder-Sheker turned me into a harper, revealing in her teaching and her life the holiness of music.

Bethanny Forest and Laura Henning were my bandmates. They listened to my occasional ravings about magic and kept me focused on the serious business of making noise.

Mike Marlier told me horror stories of musicians on the road. Wendy Luck read each chapter with approval and cheers. Nancy Keogel read the first draft and suggested a critical change. Kyira Brooke kept the faith. Paulie Rainbow checked the revised manuscript. My beloved Mirya provided encouragement, made sure that I ate, and reminded me that chapter 14 is

always

a bitch. Toward the end, the Maroon Bells Morris kept my feet light and my face smiling.

My thanks to all. And especial thanks to Eugene O’Curry, whose exhaustive lectures, given in Dublin from 1857 to 1862, provided much of the foundation for the book.

Chick with a harp.

Her hair was the color of an angry sunset, and it fell to her waist in ripples of copper and red. Her steps— deliberate, prideful, measured—took her eastward along Evans Avenue through clouds of dust raised by the summertime street repair. People stared at the small, wire-strung harp she carried tucked under her arm. She did not appear to notice.

Shielding his eyes from the June sun that glared through the tinted windows of the guitar school, Kevin Larkin watched her. Blue blouse, beige slacks, red hair: she looked as summery as the day, and he smiled in spite of his headache and rested his eyes and his mind on the pretty harper. From an office down the hall drifted a simple arrangement of “Wildwood Flower” on acoustic guitar, the sweet country strain an appropriate soundtrack to accompany her along the dusty street.

But with that harp—and that hair—the tune should have been Irish. Something ancient. Kevin recalled the Ossipanic ballads that his grandfather used to sing, the old man’s resonant voice belying the frequent gasps of unchecked emphysema that interrupted his song. How did that one go? It had been years now, and Kevin—millennia from Ossian and decades from his grandfather—struggled a moment to remember, his hands falling to the electric guitar slung from his shoulder, picking out attempts at the melody in an unamplified whisper:

Stiurad me dod mho

… something…

Cia nach ollamh… eigir

… how was that?

… di… dum… di… But it would not come. The cadences were strange, and his inner ear, conditioned by years of, rock and roll and by the involuted simplicity of the blues, lost the melody and left him stranded and groping. He felt stale, empty. The music that he knew and taught had long ago been worn smooth and featureless with overhandling, and his grandfather’s song eluded his grasp.

In the background, “Wildwood Flower” finished in a light strum and the crystalline spark of a harmonic.

“Nice, Dave,” Kevin said aloud. “Do you know anything Irish?”

“Don’t you?” came the voice of the other teacher. “You’re the Paddy.”

“Gave it up for Lent.”

“Oh, sure.” Dave whacked out a raucous series of chords, and after a moment his voice rang out in a sardonic imitation of an Irish tenor:

“

Oh, Danny Boy

…”

“Stuff it,” Kevin yelled. A denim-and-leather-clad student who was waiting for a lesson looked up at him, startled. Kevin realized that there had been genuine anger in his voice. “Uh… sorry, Jake,” he said. “Be with you in a minute.” Mortified, he ducked into his office and closed the door.

Ossian was far fled now, and Kevin regretted it. Something about that melody. Very Irish—Celtic, rather—very clear, very pristine. But his grandfather had died and taken the songs with him, and Kevin’s father and mother cared little for anything Irish except the Church.

Kevin ran his hand along the slender neck of his guitar, grimacing. Ossian had been forgotten, and music too, and perhaps also a son who had possessed the audacity to tell old Father Lynch to go piss up a rope.

Gave it up for Lent

. Oh, sure, a nice Catholic boy. Glib as a tinker with a pint, and thrown out of the house for it as an example to his three sisters and his little brother, Danny.

He tipped his chair back, kicked away some of the clutter on his desk, and propped his feet up. Danny had, he supposed, gone on to the seminary. Jeanine, Marie, and Teresa had probably married. He did not know for sure. It had been twenty years.

A poster of Jimi Hendrix stared down at him from the wall beside an old slide guitar that hung from a piece of red twine. Kevin felt for the Ossipanic strain unsuccessfully. Coming as it did from another land and another age, the music was very different from rock and roll. Maybe there was something about it that he could use to break the petrification growing within him. He was feeling desperate, afraid that, one fine day, a student like Jake was going to point at him in mid-lesson and call him a fraud, an old man who had lost the music, who had no business teaching rock and roll.

Malmsteen was playing tomorrow night. Heavy metal and Paganini. Wild combination. It might break the spell.

But Malmsteen was tomorrow. Today he hunted for Ossian. For a moment, he rested his mind on the image of the girl with the harp. Summery. Lovely.

A ghnuir anglidhe

… what was it… no…

Damn.

The brass bell above the door of Best’s Guitar Laboratory clanged once, twice, then settled down to a mellow reverberation that faded in the warm air. Roger looked up from the Les Paul that play on the carpeted counter and nodded to the young woman who had entered. “Afternoon, Christa. I’ll be with you in a min.” He noticed then what she carried. “No problem with the harp, I hope.”

“None, Roger. It’s only some stain I need and I want to be sure of the color.” Christa sat down on the rickety chair by the front window and laid the small harp across her lap. She glanced curiously at the young man who, in wild hair, a ripped T-shirt, and pink jeans, stood across the counter from Roger.

Roger grinned at her, flicked his short ponytail back over his shoulder, and bent over the guitar again. “This has seen some hard times, Tony,” he commented.

“Well, like I found it in this pawnshop up on Broadway,” Tony explained. “The guy didn’t know what he had. I saw the PAF pickups, and I knew it was for me.”

“PAFs give a nice sound…” Roger lifted the instrument by its headstock and squinted down the neck. “Ummm… frets are kind of funky.”

“I’d be funky too if I was hanging up by a heater for a couple years. Can you make it right?”

Roger estimated with a luthier’s instinct. Probably a ’58. Good year for a Paul. He could have looked up the serial number, but he was fairly sure of it.

He ran his hand across the scarred face of the guitar, his fingers tracing gouges, splits, cracks, dents. Why did people treat instruments like this? Even the cheapest piece-of-shit import deserved better than to be left hanging by a heater. The wood, already dry from the arid Denver climate, had dried even more, shrinking, breaking the bindings, splitting the fingerboard…

The Buddha is everywhere, he thought. But if he’s in front of a hot ventilator, he’s not smiling.

His hands continued to probe. Electronics could be repaired easily enough. And the pickups seemed fine. But the soul of a guitar—of any instrument—was in the wood.

“I can’t make it perfect,” he said, playing it gently down on the carpet as though to make up for the abuse it had suffered. “I can make it playable. But I can’t say for sure what might happen in the future. Could split wide open someday.”

“You’re not sure?”

“Can’t say. Things can happen.”

The young man hesitated. Roger had worked on his guitars for several years, and he knew that Tony had probably committed himself to living on beans and fruit cocktail for several weeks in order to buy the Les Paul. Even a partial restoration would increase the period of beans and cocktail to two or three months. And then if the guitar died anyway…

Roger looked over at Christa. She had been staring at the harp, her face troubled, her thoughts obviously far away, but she raised her head. “Is it help you need?”

“You want to take a look?” Roger stepped back with a nod to Tony. “Christa knows wood. She does all her own work on her harps.”

“Is that what that thing is… ?”

Laying her instrument aside, Christa came to the counter, rested her hand on the guitar. She was silent for a better part of a minute, then: “Oh dear.” Tony started to speak, but she shushed him and bent her head.

After another minute, she straightened, shaking her head. “The heat has done it, I’m afraid,” she said. “The damage is great, and there is a weak patch of grain— look: you can see it here.” She indicated a spot near the bridge with the tip of a long fingernail. “This will be giving way in about a year.” She turned to Tony. “You said something about the… pickups?”

“Yeah. They’re PAFs. The sound is just… awesome.”

“Perhaps you can salvage them, then. Don’t worry. The spirit is gone. There will be no pain for the guitar.”

Tony looked at her, bewildered. Roger could not blame him. Christa could be a little scary at times. “I can take them out for you, Tony,” he said. “It’s no problem to drop one or both into your main axe.” He noticed that the harper’s eyes were hollow, tragic. “Are you okay, Christa?”

“I’ll be well in a moment,” she said. She shook her head, and the tragedy dispersed.

“I’ll bring in my old Kramer,” said Tony. “The rhythm slot’s empty.”

Roger nodded and helped him case the brutalized guitar. When the young man had left, he nodded to Christa. “Thanks for the help.”

“It’s sad.” Her eyes were large and blue, and he wondered how they could ever have looked so bleak. “Didn’t you feel that it was dead?”

“I think so. But I figured you’d know for sure. I’m surprised you can tell so much about an electric guitar.”

She picked up the little harp and set it on the counter. “Music is music. That guitar came from a factory, but it had a spirit nonetheless. And now it’s gone. That’s sad for any instrument, not just for harps.”

“I know what you mean.” Roger was looking over the harp. There was a scratch along the length of the soundbox, but the damage had been expertly smoothed and buffed. Christa’s work. “What’s this?”

Christa sighed. “I’m sorry, Roger. One of my little students bumped into it and knocked it down. I did what I could, but I don’t have the same stains as you.”

Roger nodded slowly as he ran his fingers along the scratch. “It’s kind of an oddball color. When I built the wife’s first harp, I wanted it to look as though it was still alive, so I mixed this up, and I got to like it. I can give you a little, if you want to finish the job.”

“I do, surely. I’m ashamed to bring one of your children back like this.”

“No problem. Things happen. C’mon, I’ll show you the workshop.”

He led her down a short hall and into a large room full of tools, electronic parts, and cans of lacquer, stain, and varnish. Hanging from pegs and hooks, and lying on benches and tables, were a number of guitars in various degrees of completion. Rosewood and ebony glowed in dark shades of sable and brown. Maple gleamed yellow, and brown heart and amaranth shown with ruddy color.

Roger selected a can of stain, pried it open, and poured a bit of the dark liquid into a clean bottle. “There you are,” he said, capping it. “Anything else? How about an electric guitar?”

He was proud of his work. His guitars looked alive, and surrounded as he was by his instruments, his pain at the mutilated Les Paul dimmed a little. Order and disorder. His job was to mold a little art out of chaos, something that would hold together for a while and bring a little joy to someone. But, yin and yang, everything had to come around again, and he had long ago accepted that whatever he made would have to return eventually to its beginnings. His art lasted only for a few instants of eternity: a blink of the Buddha’s eye. Change was inevitable. Sad it was, but wonderful too.

Christa peered at the guitars just as Tony had stared at her harp. Roger smiled at the contrast between the quiet harper and the electric instruments about her. He wondered sometimes if she had been raised in a convent.

“No harps, Roger?” she said, turning around.

“No orders. The last one I built was for that girl you sent to me a few months back. What was her name? She’s a rocker… plays bass…”

“Melinda Moore?”

“Yeah. Melinda. Good bass player. Anyway, that was it. Now, for guitars I have lots of orders. Fortunately.”

“They’re lovely, Roger,” she said. “It’s like walking through a forest. I thought, though, that electric guitars were supposed to be…” She paused before a nearly complete instrument, cautiously picked a steel string with the tip of a fingernail. “… strange colors.”

“MTV guitars?” He frowned, shook his head. “Wood’s pretty enough, even for heavy metal. It’d be easy to slap on three coats of day-glo polyurethane and call it done, but I want my kids to look alive. Kinda… druidical, if you know what I mean.”

Her eyebrows lifted for a moment, but she smiled. “Well, not exactly druidical. But… sylvan.”

“Let me know when you want to start rocking, Christa. I’ve got some beautiful wood sitting in back. I can really see the kind of guitar I’d build for you.”

For years he had played with the idea, letting his imagination range about while he sanded, or buffed, or soldered pots and capacitors. What kind of guitar would he make for this pretty harper with her sweet voice and strange manners, who appeared so young but who seemed at times so old? It would have to glow with all the luster of her hair, and he knew he would have to give to it the feeling of ancient forests, of standing stones and misty dawns. Nothing else would be appropriate. Nothing else would fit.

Christa was laughing. “I really cannot see myself in pink jeans and spiked hair, Roger. But if ever I need an electric guitar, you’ll be the one to build it.”

“Hey, I’ll hold you to that. About when hell freezes over, right?”

“Oh, I don’t think it will be that soon. Do you?”

Roger shrugged. “Things happen. Never can tell.”