Good Things I Wish You (18 page)

Read Good Things I Wish You Online

Authors: Manette Ansay

“She.”

“Ah.”

“She ran a background check on you.”

“At your request?”

“Her own initiative, actually.”

“An enterprising woman.”

“More like a concerned friend.”

“And what, in particular, concerns her?”

What I thought: What doesn’t?

What I said: “You tell me.”

Behind his shoulder, the countryside flashed by: open fields populated by cattle and goats; steep vineyards; exposed rock; scattered outcroppings of slope-shouldered pine. Beautiful countryside. Beautiful land. I wanted to scoop it up by the bucketful, drink it down in gulps, wash away my suburban South Florida life of billboards and strip malls, asphalt and road trash, terrible traffic and the sort of heat that begins to feel something like rage. Even here, it clung to me still, like burned and blistered skin. I wanted this place to be the one I called home, even as I struggled to speak its language, even as I knew that, in another week, I’d be back in the world where, no doubt, I’d come to belong. Neither vibrant city nor lyrical country but the undefined space in between. Staring out my window at the artificial lake. Walking the beach with my face turned toward the water, away from the condos, the shops and parking lots.

“What is there to tell?” Hart said. “I should not have taken her out of France. I should not have kept her so long.”

“Where did you take her?”

“La Scala. The London Philharmonic. Tanglewood.” He cocked his head. “What, you were expecting a dungeon?”

“I wasn’t expecting

Disneyland

.”

“It was where she wanted to go. Our last stop.”

“Your last stop before what?”

“Before it was time to take her back home.”

“You were going to take her back to France?”

“I’d sent Lauren our itinerary. She turned it over to the French authorities, who turned it over to the Americans. That is how I came to be arrested in front of—what is that ride? The one with the planets? Space station?”

“Space Mountain?”

“Yes, it is just this otherworldly. They put me into handcuffs. You can imagine the mess. I lost interest in my research, I still cannot explain. I took a leave of absence. I traveled out west for a year.”

“Where you ended up in the hospital.”

“Your concerned friend, I’m sure, has told you about that, too.”

“Not really,” I said, but he was getting to his feet.

“Quick, before I kidnap you. We are coming to our stop.”

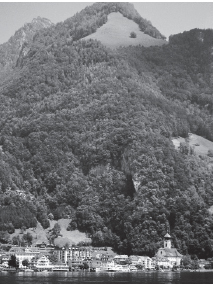

The last ferry was about to leave; we bought our tickets, stepped aboard. Minutes later, we were sliding through the green waters of Lake Lucerne. Mount Pilatus behind us. The Rigi like a muscular shadow ahead. Upstairs in

the dining room, Hart surprised me by ordering champagne.

“Now, for happier topics,” he said as the waitress put out our glasses. “Friederike attends the Juilliard this fall. It is settled to everyone’s satisfaction. So it’s doubtful, I think, that Swiss guards shall arrive—tonight, at least—to carry me away.”

“Congratulations,” I said.

“Yes, yes, it is a wonderful thing. I will relocate to New York, buy an apartment, pay a housekeeper to greet her after school and care for her when I travel. Of course I will cover Friederike’s tuition and expenses. Meanwhile, should Lauren feel the emotional loss of her daughter too intensely, I shall continue paying child support as a means of cushioning such strong, maternal grief. Should her soon-to-be husband benefit from such considerations, well, such an effect must be considered incidental.”

“You will move to New York,” I repeated. For some reason, this hadn’t occurred to me: that Hart would be going with her.

“In exchange, Lauren does not sue me in court for more alimony, to which she is likely entitled. My attorneys assure me it comes out the same. Ah, the sweet fruits of justice.”

“You have plenty of money,” I said quietly.

Hart looked at me. “This is true.”

“And now you have your daughter. So, in the end, you are the lucky one, just as you always tell me. You are the one who has everything.”

“Not everything, no.” He refilled his glass. “But perhaps you would agree to come with us? You told me once that you missed living there.”

“And my suitcase is already packed. So why not?”

“Your daughter will come too, of course. There you’ll have access to the sort of teachers, the sort of environment…well, isn’t that what you are wanting for her?”

I stared at him. “You are serious.”

“Come, how difficult can this be? I will get to know your Heidi, she will get to know me.” He topped off my champagne. “As for your teaching, I am guessing you could find another position, if you wish. But wouldn’t you rather just write your books? Did I ever tell you the story of how Friederike came to play the violin?”

I shook my head, still trying to wrap my mind around the question at hand.

“She was eight. Lauren and I were just married for the second time. A colleague of mine invited us for a week in the Bordeaux countryside. One night at dinner, someone starts to play the piano, and we’re thinking it must be his daughter when the daughter herself walks in.

Friederike won’t take turns,

she announces, and I get up to see my Friederike playing the same piece this girl had performed for us just the night before. All the way back to Paris, Lauren and I argue about what to do.

Anything but the piano!

she says.

It will only spoil her hands.

In the end, Friederike gets a violin.”

“Well, it seems to have worked out.”

“In New York, you could supervise Friederike’s practicing. You could be there to care for her when I must be away. You could advise her as only a woman can.”

I pushed back my glass, dismayed. “Are you asking me there as your lover or as the household manager you’re reluctant to hire?”

“Neither. Both.” He looked at me earnestly. “I am asking you there as my wife.”

“Are you absolutely crazy?”

“A reaction I’ve not yet experienced,” he said drily.

“We’ve known each other three months!”

“How long did you know Cal before you married him?”

“Three years.”

“I knew Lauren two years the first time, ten the second. For all the damn good it did us. Come, we both have attorneys. We will write a solid prenup. I get along with you, I suppose, as well as I’ve gotten along with any woman.”

I flushed. “How romantic of you to say so.”

“Don’t be that way, Jeanette,” he said, and I saw he was hurt, too. “Would you rather I tell you a lie? What can romance mean at our age? I am thinking we understand each other.”

The town of Gersau appeared on the horizon: an onion-headed steeple, surrounded by houses set into the mountainside. At a restaurant across the street from the station, we asked for directions to the town’s only inn. By now the light was fading fast, and together we walked up the steeply sloped path as he talked of music and sunlight and trees. Of stones, of sour cherries. Of history and God,

diseases of the nerves, augmented chords, a restaurant in Dresden where, once, he had sampled a particular kind of cheese. But I couldn’t keep up with all that he said. I couldn’t keep up with my own flooding heart. This was not the sort of man with whom one builds a future. And yet I could not step away.

“Why were you hospitalized?” I asked.

“We are back to that.”

“We are back to that.”

Around us, the darkening land. The fading light of dreams.

“Long before reading poor Schumann’s story, I had the misfortune to jump off a bridge.”

“Stupid,” I said. It just came out.

“Yes, my dear, strong Jeanie,” he said. “Stupid indeed. Particularly when you consider how very well I swim.”

Gersau, 2006

39.

“I

T IS SOMETHING OUT

of my childhood,” Hart said, staring at the narrow bed, the washbasin, the window shutters thrown open in the hope of attracting the slightest breeze. Cooking smells thickened the air. The bath was down the hall. The overhead light didn’t work, but there was an electric candle on the nightstand and—another touch of whimsy—a small golden cherub mounted above the bed. “Is this the inn where they stayed?”

“Possibly. The house was here, but I don’t know which years it served as an inn.”

We took turns washing up for the night, then lay naked on top of the sheets. Too hot to touch. Too hot to sleep.

“I wish,” Hart said, “I had something to read.”

“I’ve got a book, if you want it,” I said, reaching for the short-story anthology I still hadn’t managed to finish.

“You do have a book, yes.” Hart took the anthology, placed it like a brick between us. “But I’m thinking of the one on your laptop. When do I get to read what you are writing?”

Our bodies looked strange in the false candlelight, each of us neither old nor young. “I should tell you something first,” I said. “Something I should have told you before.”

Hart touched the anthology with one finger. “I’ve never enjoyed any conversation which begins this way.”

“I’ve been writing about you,” I said.

For once, he had nothing to say.

“Not

you

, of course,” I added. “Everything changes when it hits the page. But there are things you’re going to recognize. Not because they’re true, but because they’re not. The same way that anyone who knows Clara’s life will recognize—”

“Clara’s life, yes. A woman born in 1819. I thought you were writing a historical novel.”

“I thought so too.”

“What happened?”

What I thought:

I was a dead woman. I was a stone.

What I said: “There are things between men and women that do not change.”

They will spend this day as they’ve spent all the others: hiking during the relative coolness of the morning, bathing away the afternoon heat, then a few hours at the piano, taking advantage of the lingering light, taking advantage of a language in which everything between them is always understood. Sound floating over the lake like mist, climbing the steep, crooked paths between houses where conversations still to listen, where overtired children release themselves to sleep. Somewhere a nightingale repeats its circuitous lullaby. Higher up, in rough-cut pastures, drowsy-eyed cattle add the tinkling of bells.

How quiet the evenings in the absence of carriages.

How silent the nights with their showerings of stars.

Inside, as always, the air is motionless, stifling. Clara removes her dress and stockings, splashes her face with lake water. She hears Elise across the hall, still talking as the maid turns down their beds. Ferdinand and Ludwig are already sleeping in the room they share with Johannes, who makes his own soft music as he washes, moving about, humming.

It’s been a good day for them all. At last Elise is silent.

A window shutter creaks.

There comes the good smell of Johannes’s cigar, and she leans out her window, too. No need for candles; the moon is full, fierce.

They smile at each other in the clarity of its light.

Usually, they walk onto the balcony, settle themselves in rocking chairs that face the water and, beyond the water, the foothills of the Alps. Johannes carries his candle for them both, a single, flickering heart, and at some point, they find themselves holding hands. For the rest of her life, she will think of that hand, small and smooth and remarkably delicate. A woman’s hand, if she did not know better, dwarfed by her own massive palm. She will think of the smell of Johannes’s cigar, the high, boyish murmur of his voice. The faint lapping sounds of other voices, other balconies, other lovers waiting for the heat to ease, returning to their beds, turning to each other, houses so close that this music, too, becomes part of the night, part of all of the nights in which Clara has lain sleepless, aching, a single thin wall the only thing that divides her from what she wants.

Tonight, she is tired of waiting. Tired of longing. This terrible restlessness that won’t let her sleep. The thoughts that torment her, unspeakable, consuming. Perhaps she is tasting what poor Robert tasted. Perhaps she too is going mad. Certainly it is madness that prompts her to take Johannes by the hand and lead him not to the balcony chairs, but down the wooden steps into the landscaped courtyard, through the gate and onto the stony path they’ve climbed so many times with the children in the freshness of morning, in the brightness of day, gathering flowers, admiring the scattered outcroppings of rock embedded in the Rigi’s green face. Perhaps it is the wide, curious eye of the moon that propels her to walk faster, even as she feels him start to resist, as the silence between them grows shadowed and thick, uncomfortable as the humidity, oppressive as the heat.