Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (88 page)

Read Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid Online

Authors: Douglas R. Hofstadter

Tags: #Computers, #Art, #Classical, #Symmetry, #Bach; Johann Sebastian, #Individual Artists, #Science, #Science & Technology, #Philosophy, #General, #Metamathematics, #Intelligence (AI) & Semantics, #G'odel; Kurt, #Music, #Logic, #Biography & Autobiography, #Mathematics, #Genres & Styles, #Artificial Intelligence, #Escher; M. C

Crab: What do you mean by "self-engulfing", Achilles?

Achilles: I mean, when I point the camera at the screen-or at part of the screen. THAT'S

self-engulfing.

Crab: Do you mind if I pursue that a little further? I'm intrigued by this new notion.

Achilles: So am I.

Crab: Very well, then. If you point the camera at a CORNER of the screen, is that still what you mean by "self-engulfing"?

Achilles: Let me try it. Hmm-the "corridor" of screens seems to go off the edge, so there isn't an infinite nesting any more. It's pretty, but it doesn't seem to me to have the spirit of self-engulfing. It's a "failed self-engulfing".

Crab: If you were to swing the TV camera back towards the center of the screen, maybe you could fix it up again ...

Achilles (slowly and cautiously turning the camera): Yes! The corridor is getting longer and longer ... There it is! Now it's all back. I can look down it so far that it vanishes in the distance. The corridor became infinite again precisely at the moment when the camera took in the WHOLE screen. Hmm-that reminds me of something Mr. Tortoise was saying a while back, about self-reference only occurring when a sentence talks about ALL of itself ...

Crab: Pardon me?

Achilles: Oh, nothing just muttering to myself.

(As Achilles plays with the lens and other controls on the camera, a profusion of new kinds of self-engulfing images appear: swirling spirals that resemble galaxies, kaleidoscopic flower-like shapes, and other assorted patterns ...) Crab: You seem to be having a grand time.

Achilles: (turns away from the camera); I’ll say! What a wealth of images this simple idea can produce! (He glances back at the screen, and a look of

astonishment crosses his face.) Good grief, Mr. Crab! There's a pulsating petal-pattern on the screen! Where do the pulsations come from? The TV is still, and so is the camera.

Crab: You can occasionally set up patterns which change in time. This is because there is a slight delay in the circuitry between the moment the camera "sees" something, and the moment it appears on the screen around a hundredth of a second. So if you have a nesting of depth fifty or so, roughly a half-second delay will result. If somehow a moving image gets onto the screen-for example, by you putting your finger in front of the camera-then it takes a while for the more deeply nested screens to "find out" about it. This delay then reverberates through the whole system, like a visual echo. And if things are set up so the echo doesn't die away, then you can get pulsating patterns.

Achilles: Amazing! Say-what if we tried to make a TOTAL self-engulfing?

Crab: What precisely do you mean by that?

Achilles: Well, it seems to me that this stuff with screens within screens is interesting, but I'd like to get a picture of the TV camera AND the screen, ON the screen. Only then would I really have made the system engulf itself. For the screen is only PART of the total system.

Crab: I see what you mean. Perhaps with this mirror, you can achieve the effect you want.

(The Crab hands him a mirror, and Achilles maneuvers the mirror and camera in such

a way that the camera and the screen are both pictured on the screen.)

Achilles: There! I've created a TOTAL self-engulfing!

Crab: It seems to me you only have the front of the mirror-what about its back? If it weren't for the back of the mirror, it wouldn't be reflective-and you wouldn't have the camera in the picture.

Achilles: You're right. But to show both the front and back of this mirror, I need a second mirror.

Crab: But then you'll need to show the back of that mirror, too. And what about including the back of the television, as well as its front? And then there's the electric cord, and the inside of the television, and

Achilles: Whoa, whoa! My head's beginning to spin! I can see that this "total self-engulfing project" is going to pose a wee bit of a problem. I'm feeling a little dizzy.

Crab: I know exactly how you feel. Why don't you sit down here and take your mind off all this self-engulfing? Relax! Look at my paintings, and you'll calm down.

(Achilles lies down, and sighs.)

Oh-perhaps my pipe smoke is bothering you? Here, I'll put my pipe away. (

Takes the pipe

from his mouth, and carefully places it above some written words in another .Magritte

painting.

) There! Feeling any better?

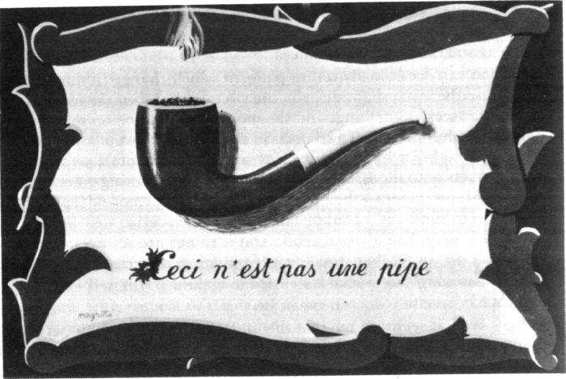

Achilles: I’m still a little woozy, (Points at the Magritte.) That’s an interesting painting. I like the way it’s framed, especially the shiny inlay inside the wooden frame.

FIGURE 82. The Air and the Song, by Rene Magritte (1964).

Crab: Thank you. I had it specially done-it's a gold lining.

Achilles: A gold lining? What next? What are those words below the pipe? They aren't in English, are they?

Crab: No, they are in French. They say, "Ceci n'est pas une pipe." That means, "This is not a pipe". Which is perfectly true. 4chilles: But it is a pipe! You were just smoking it!

Crab: Oh, you misunderstand the phrase, I believe. The word "ceci" refers to the painting, not to the pipe. Of course the pipe is a pipe. But a painting is not a pipe.

Achilles: I wonder if that "ceci" inside the painting refers to the WHOLE painting, or just to the pipe inside the painting. Oh, my gracious! That would be ANOTHER self-engulfing! I'm not feeling at all well, Mr. Crab. I think I'm going to be sick ...

Self-Ref and Self-Rep

IN THIS CHAPTER, we will look at some of the mechanisms which create self-reference in various contexts, and compare them to the mechanisms which allow some kinds of systems to reproduce themselves. Some remarkable and beautiful parallels between these mechanisms will come to light.

Implicitly and Explicitly Self-Referential Sentences

To begin with, let us look at sentences which, at first glance, may seem to provide the simplest examples of self-reference. Some such sentences are these: (1) This sentence contains five words.

(2) This sentence is meaningless because it is self-referential.

(3) This sentence no verb.

(4) This sentence is false. (Epimenides paradox)

(5) The sentence I am now writing is the sentence you are now reading.

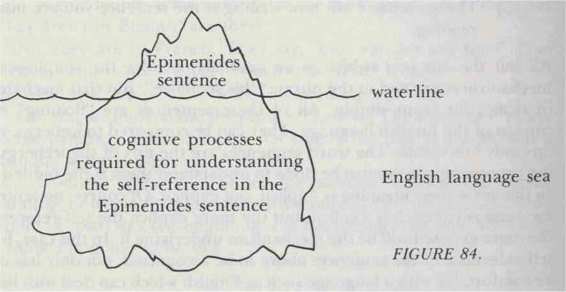

All but the last one (which is an anomaly) involve the simple-seeming mechanism contained in the phrase "this sentence". But that mechanism is in reality far from simple. All of these sentences are "floating" in the context of the English language. They can be compared to icebergs, whose tips only are visible. The word sequences are the tips of the icebergs, and the processing which must be done to understand them is the hidden part. In this sense their meaning is implicit, not explicit. Of course, no sentence's meaning is completely explicit, but the more explicit the self-reference is, the more exposed will be the mechanisms underlying it. In this case, for the self-reference of the sentences above to be recognized, not only has one to be comfortable with a language such as English which can deal with linguistic subject matter, but also one has to be able to figure out the referent of the phrase "this sentence". It seems simple, but it depends on our very complex yet totally assimilated ability to handle English. What is especially important here is the ability to figure out the referent of a noun phrase with a demonstrative adjective in it. This ability is built up slowly, and should by no means be considered trivial. The difficulty is perhaps underlined when a sentence such as number 4 is presented to someone naive about paradoxes and linguistic tricks, such as a child. They may say, "What sentence is false and it may take a bit of persistence to get across the idea that the sentence is talking about itself. The whole idea is a little mind

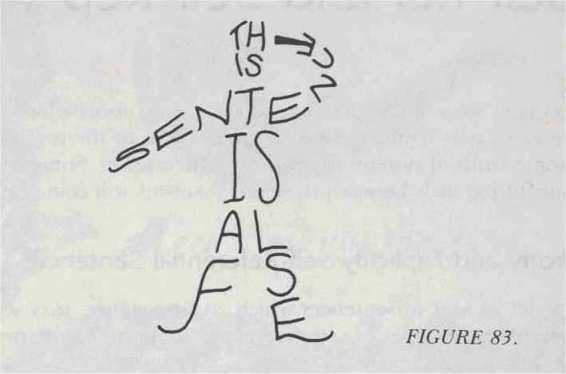

boggling at first. A couple of pictures may help (Figs. 83, 84). Figure 83 is a picture which can be interpreted on two levels. On one level, it is a sentence pointing at itself; on the other level, it is a picture of Epimenides executing his own death sentence.

.

Figure 84, showing visible and invisible portions of the iceberg, suggests the relative proportion of sentence to processing required for the recognition of self-reference: It is amusing to try to create a self-referring sentence without using the trick of saving this sentence". One could try to quote a sentence inside itself. Here is an attempt: The sentence "The sentence contains five words" contains five words.

But such an attempt must fail, for any sentence that could be quoted entirely inside itself would have to be shorter than itself. This is actually possible, but only if you are willing to entertain infinitely long sentences, such as:

The sentence

"The sentence

"The sentence

"The sentence

…

….

etc,.,etc.

…

….

is infinitely long"

is infinitely long"

is infinitely long'

is infinitely long.

But this cannot work for finite sentences. For the same reason, Godel's string G could not contain the explicit numeral for its Godel number: it would not fit. No string of TNT can contain the TNT-numeral for its own Godel number, for that numeral always contains more symbols than the string itself does. But you can get around this by having G contain a

description

of its own Godel number, by means of the notions of "sub" and

"arithmoquinification".

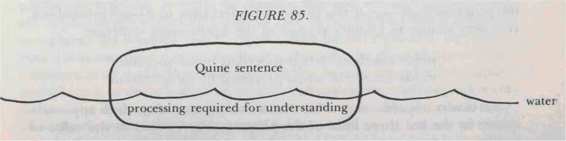

One way of achieving self-reference in an English sentence by means of description instead of by self-quoting or using the phrase "this sentence" is the Quine method, illustrated in the dialogue

Air on G's String

. The understanding of the Quine sentence requires less subtle mental processing than the four examples cited earlier. Although it may appear at first to be trickier, it is in some ways more explicit. The Quine construction is quite like the Godel construction, in the way that it creates self-reference by describing another typographical entity which, as it turns out, is isomorphic to the Quine sentence itself. The description of the new typographical entity is carried out by two parts of the Quine sentence. One part is a set of instructions telling how to build a certain phrase, while the other part contains the construction materials to be used; that is, the other part is a

template

. This resembles a floating cake of soap more than it resembles an iceberg (See Fig. 85).