Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (17 page)

Read Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right Online

Authors: Jennifer Burns

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #Philosophy, #Movements

Still, Rand feared she wasn’t reaching her kind of readers. Most distressing were the ads for

The Fountainhead,

which presented the book as an epic romance rather than a serious treatment of ideas. She fired off an angry letter to Archie Ogden, detailing her dissatisfaction. Before long she took action herself, resurrecting her earlier political crusade, but now tying it directly to the fortunes of her novel. As she explained to Emery, she wanted to become the right-wing equivalent of John Steinbeck: “Let our side now build me into a ‘name’—then let me address meetings, head drives, and endorse committees. . . . I can be a real asset to our ‘reactionaries.’” The key would be promoting

The Fountainhead

as an ideological and political novel, something Bobbs-Merrill would never do.

53

Rand was careful to explain that her ambitions were not merely personal. The problem, she explained to Emery and several other correspondents, was that the intellectual field was dominated by a “Pink-New-Deal-Collectivist blockade” that prevented other views from being heard. This was why books like

The Fountainhead

were so important: If it went “over big, it will break the way for other writers of our side.” Rand was convinced “the people are with us”; it was leftist intellectuals who stood in the way.

54

She set up meetings with executives at DuPont and the National Association of Manufacturers and pressed Monroe Shakespeare to pass her book along to Fulton Lewis Jr., a right-wing radio host.

In the end Hollywood gave

The Fountainhead

the boost it needed. The idea of a movie was particularly tantalizing to Rand. The novel was selling well, but she still worried it would suffer the same ignominy as

We the Living

. A movie would put her name before a wide audience and ensure the book’s longevity. Rand turned down her first film offer only weeks after publication, sure her book would become more valuable with time. In the fall of 1943 her new agent reported a more promising proposal from Warner Brothers. Rand drove a hard bargain. After nearly two decades in the industry she had learned her lesson. “Red Pawn,” the first scenario she sold, had doubled in price soon afterward, netting a tidy profit for the studio, which she had never seen. She would settle for nothing less than fifty thousand dollars, a princely sum. Scarcely two years earlier she had leapt at a paltry advance of a thousand dollars. Warner Brothers balked at the demand, but she wouldn’t budge.

In November the offer came through. Almost better than the money was the studio’s interest in having her write the script. It meant that she and Frank would return to Hollywood, a prospect Rand dreaded. But only by being there in person, Rand knew, could she hope to ensure the integrity of her story and preserve the essence of her ideas. Warner Brothers even dangled before her the prospect of consulting on the film’s production. When the deal was finalized Frank and Isabel Paterson bundled her into a taxicab and set off for Saks Fifth Avenue. “You can get any kind of fur coat provided it’s mink,” Frank told his wife.

55

Rand’s instinct was to hoard the money, to save every penny so she would always have time to write. Frank and Isabel knew better. After so many years of hard work, Rand had finally become a “name.”

PART II

From Novelist to Philosopher, 1944–1957

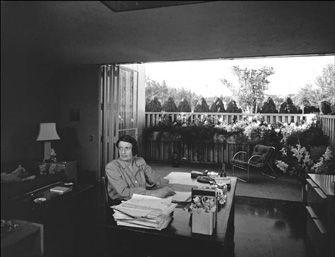

Ayn Rand in her Chatsworth study where she began the writing of

Atlas Shrugged

. J. Paul Getty Trust. Used with permission. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at The Getty Research Institute (2004. R. 10).

CHAPTER FOUR

The Real Root of Evil

AYN AND FRANK

arrived in Hollywood as celebrities.

The Fountainhead

was the hot property of the moment, and the town buzzed with speculation about who would be chosen for the choicest roles. Stars began to court Rand in the belief that she could influence the studio’s choices. Joan Crawford threw a dinner for the O’Connors and came dressed as Dominique, in a long white gown and aquamarines. Warner Brothers set her up in an enormous office with a secretary out front and a $750 weekly salary. The contrast between Rand’s arrival as a penniless immigrant in 1926 and her latest debut was sharp.

The Golden State’s charms were lost on Rand, who complained about “the disgusting California sunshine.”

1

Her heart was still in New York, and she hoped their time in California would be brief. She immediately set to work on

The Fountainhead

script, turning out a polished version in a few weeks. There would be no quick return east, however, for production of the film was suspended indefinitely due to wartime shortages. Rand resigned herself to a lengthy stay in California. When her work for Warner Brothers was done, she signed a five-year part-time screenwriting contract with the independent producer Hal Wallis, successfully negotiating six months off a year to pursue her own writing. She and Frank bought a house that perfectly suited them both, an architecturally distinguished modernist building that could easily have graced the pages of

The Fountainhead

. Designed by Richard Neutra and situated in rural Chatsworth, almost an hour’s drive from Hollywood, the glass-and-steel house was surrounded by a moat and thirteen acres. In the end, they would live there for seven years.

Rand underwent two profound intellectual shifts during her time in California. The first was a reorientation of her thought toward a concept

of reason she linked with Aristotle. When she arrived in California she was working on her first nonfiction book, a project she eventually abandoned in favor of her third novel. Much as

The Fountainhead

had showcased her ideas about individualism, this next book would reflect Rand’s growing fealty to reason and rationality. After three years in California Rand had redefined the goal of her writing. Once individualism had been the motive power of her work; now she explained to a correspondent, “Do you know that my personal crusade in life (in the philosophical sense) is not merely to fight collectivism, nor to fight altruism? These are only consequences, effects, not causes. I am out after the real cause, the real root of evil on earth—the irrational.”

2

Soon after this development came Rand’s dawning awareness of the differences that separated her from the libertarians or “reactionaries” she now considered her set. At issue was her opposition to altruism and, more significantly, her unwillingness to compromise with those who defended traditional values. In 1943 Rand had been one of the few voices to make a compelling case for capitalism and limited government. In the years that followed she would become part of a chorus, a role that did not suit her well.

Rand’s move back to Hollywood immersed her in a cauldron of political activity that was dividing the film industry. The first stages of the Red Scare that would sweep the nation were already unfolding in California. Labor troubles paved the way. In 1945, shortly after her return, the Conference of Studio Unions launched an industry-wide strike, touching off a heated conflict that would last for nearly two years. At the gates of Warner Brothers rival unions engaged in a full scale riot that garnered national headlines and aroused the concern of Congress. Ensconced in far-away Chatsworth, Rand missed the excitement. She quickly signed on, however, with a group formed to oppose Communist infiltration of the entertainment unions and the industry more broadly, the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. The group was founded by powerful Hollywood figures, including Walt Disney, John Wayne, and King Vidor, director of

The Fountainhead

. At the first meeting she attended Rand was surprised to be unanimously voted onto the Executive Committee.

Just as she had once dreamed, Rand was being tapped to head committees and lead drives, to lend her fame to a political cause. She also joined the board of directors of the American Writers Association, an alliance of writers formed to oppose the “Cain Plan,” a proposed authors’ authority. Under the plan, which was supported by the Screenwriter’s Guild and a union of radio writers, the new authority would own copyright and marketing rights of authors’ products. Rand and others immediately detected Communist agents at work. The American Writers Association sent representatives to a meeting of the Authors League in New York, held several meetings, and began publishing a newsletter. Rand was active in bringing several of her Hollywood connections aboard, where they joined a prominent line-up of literary stars, including Dorothy Thompson, Hans Christian Andersen, Margaret Mitchell, and Zora Neale Hurston. Through them Rand met another group of right-wing activists, including Suzanne LaFollette, Clare Boothe Luce, Isaac Don Levine, and John Chamberlain. When the Cain Plan was soundly defeated, the American Writers Association attempted to extend its ambit to a defense of writers who had suffered from political discrimination, but it soon lapsed into inactivity.

3

Rand was also taken up by business conservatives such as Leonard Read, head of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, who invited her to dinner with several associates soon after she arrived in California. The driving force behind the dinner was R. C. Hoiles, publisher of the L.A.-area

Santa Ana Register

. Hoiles had given his family copies of

The Fountainhead

, praised the book in his column, and swapped letters with Rand while she was still in New York. The dinner created no lasting bond between the two, perhaps because Hoiles liked to support his libertarianism with quotes from the Bible, but he continued to promote Rand in his Freedom Newspapers, a chain that eventually grew to sixteen papers in over seven western and southwestern states.

4

Rand was more impressed by William C. Mullendore, an outspoken executive at Con Edison. Mullendore admired

The Fountainhead

and in turn she considered him a “moral crusader” and the only industrialist who understood “that businessmen need a philosophy and that the issue is intellectual.” It was Mullendore who had converted Read to the “freedom philosophy,” and under his tutelage Read transformed his sleepy branch of the Chamber of Commerce into a mouthpiece for

libertarianism and a quasi–think tank, complete with a lecture series and educational programs. Stepping into an ideological vacuum, within a few years Read was able to “set the tone of the Southern Californian business community,” as one historian observes.

5

Read’s activities built on larger trends shaping the region and the nation. With the war at its end and the economy recovering, business conservatives began to mount organized opposition to the New Deal order. Chief among their targets was organized labor. A wave of strikes and slow-downs that swept the country in 1945 was their opportunity. Business owners argued that labor had gained too much power and was becoming a dangerous, antidemocratic force. On the state level “right to work” laws, which outlawed the closed shop and other union-friendly measures, became political flashpoints, particularly in the fast growing sunbelt region.

6

These initiatives were matched by developments on the national level. In 1947 the conservative Eightieth Congress overrode President Truman’s veto to pass the Taft-Hartley Act, a piece of legislation that rolled back many of the gains labor had made during Roosevelt’s administration. Hoiles and Mullendore were emblematic of this new militancy, both taking a hard line when strikes hit the companies they managed.

Read, Mullendore, and Hoiles rightly recognized Rand as a writer whose work supported their antiunion stance. It had not escaped their notice that

The Fountainhead

’s villain Ellsworth Toohey is a union organizer, head of the Union of Wynand Employees. Read and Mullendore also suspected that Rand’s more abstract formulations would resonate with businessmen. The two had a small side business, Pamphleteers, Inc., devoted to publishing material that supported individualism and free competitive enterprise. When Rand showed them a copy of

Anthem

, which had not been released in the United States, they decided to publish it in their series. As Read and Mullendore anticipated,

Anthem

was eagerly picked up by a business readership. Rand received admiring letters from readers at the National Economic Council and Fight for Free Enterprise, and another Los Angeles conservative group, Spiritual Mobilization, presented a radio adaptation in its weekly broadcast.

7

Anthem

and

The Fountainhead

became particularly appealing to business readers in the wake of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, which permitted employers to educate their employees about economic and business

matters, creating a vast new market for pro-capitalist writers.

8

Rand’s principled defense of capitalism, which focused on individualism rather than specific political issues, was a perfect fit for these corporate efforts. The editor of the

Houghton Line

, published by a Philadelphia company that manufactured oils, leathers, and metal-working products, gave

The Fountainhead

a glowing review. In a weekly circular sent to customers the owner of Balzar’s Foods, a Hollywood grocery store, referenced both

The Fountainhead

and

Anthem

and included a diatribe against the New Deal–created Office of Price Administration. A top executive at the Meeker Company, a leather goods company in Joplin, Missouri, distributed copies of Roark’s courtroom speech to his friends and business acquaintances.

9

Much as Rand had always wished, capitalists were finally promoting her work of their own volition.