God Save Texas: A Journey Into the Soul of the Lone Star State (36 page)

Read God Save Texas: A Journey Into the Soul of the Lone Star State Online

Authors: Lawrence Wright

Tags: #politics

The house I lived in, on Amarillo Street, is also still standing. I was pleased to see how nicely it is cared for. There’s a sign on the back fence saying that the house is now a member of the Society for the Preservation of Quaint Old Homes. When we lived there, the house was white, and nearly every year after a dust storm I’d have to wash it. More sensible owners have painted it a sandy color. My father had planted magnolias on either side of the door, which were still there the last time I passed by, thirty years ago. Now they’re gone, replaced by two oaks that tower over the house. The passage of time was made shockingly visible. I knocked on the door, but nobody was home. I wondered if the cork floor in the den was still scarred from my games of mumblety-peg.

Steve and I stopped in at the Grace Hotel, once the fanciest spot in town. Steve had set a scene in one of his novels there. The Grace is now a museum, and there happened to be an exhibit of Abilene in the 1950s, exactly the time when we lived there. There were mannequins wearing the clothes our parents would have worn—sack dresses and tropical shirts, in Popsicle colors of lime and orange—and appliances that had been in our kitchens. It was strange to see your own life and times laid out in front of you in a museum exhibit. “If you think about it,” Steve said, “when we moved here we were as close to the Indian wars as we are now to the day we were born.”

As we were exiting the exhibit, we came upon a street map of Abilene in 1955. I called Steve over and pointed to St. Joseph’s Academy. It was directly across the street from my elementary school.

I drove back to Austin, under a Turneresque sunset with a gibbous moon rising from a bank of pink clouds. A herd of Black Angus cattle moved like shadows in the places where the buffalo once grazed. I thought about how unintentional most of life is. Part of me had always wanted to leave Texas, but I had never actually gone. Sometimes we are summoned by work or romance to move to another existence, and for me those moments when there is no reasonable alternative to departure have always been joyful, full of a sense of adventure and reinvention. Staying is also a decision, but it feels more like inertia or insecurity. Most of the time I live in a state of vague discontent, tempted by the vision of another life but unwilling to let go of the friends and daily habits that fill my time. When I am in other states or countries, I’m always aware of being in exile from my own culture, with all its outsized liabilities. I wish I lived in the mountains of Montana or on the Spanish Mediterranean. I wish I had a condo in a high-rise overlooking Central Park, with a piano by the window. These thoughts have been at play in my imagination for decades. Now here I was, on a darkening highway in Texas, with so much more road behind me than what lay before.

I received a Texas Medal of Arts Award, along with a lot of people I have long admired, including the Gatlin Brothers, playwright Robert Schenkkan, and Jamie Foxx. At the reception, the head of the Texas State Cemetery passed through the crowd, noticing name tags. I saw him eyeing Dan Rather and T Bone Burnett. Then he approached me with a smile and said, “We’re looking forward to hosting you.”

Of all the eccentric honors that Texas can bestow on its citizens, however, admittance to the state cemetery is in every way the ultimate. It’s the Texas version of Arlington National Cemetery. The list of famous Texans interred there includes Stephen F. Austin, Barbara Jordan, and several once-well-known authors. Those who have been accepted but are still alive, like Steve, are listed as “pending.” It had been suggested that I should let my availability be known, and I had done so.

“But my application got turned down,” I told the cemetery chief. “I heard that Governor Perry vetoed me.”

“Surely not!”

“That’s what I heard.”

Perry and I had had a tiff a few years before, in his first months as governor. I was once again the emcee of the gala for the Texas Book Festival. I noticed that Perry didn’t show up. “He’s probably at a public high school leading the prayer,” I cracked, referencing a recent unconstitutional incident on the part of the new governor.

The next day, the director of the festival informed me that word of my remark had gotten back to Perry and he was demanding an apology.

“But it was a joke!”

“I know that, but the governor took offense,” she pleaded. “Now his office is threatening to withhold the use of the capitol for the festival. We’ll have to close down!”

Golly. I wrote the governor, saying I was “so sorry.” He wrote back right away, claiming that he had been raising money for paralyzed children, not snubbing the festival. He signed it, “Prayerfully, Rick.”

At the arts reception, the cemetery chief urged me to reapply. He reiterated that the governor would certainly not have stooped to such a mean-spirited action. In any case, we had a new governor, who had just given me a medal, so my chances were improved.

I wasn’t so sure I would reapply, however. Nothing says commitment like a burial plot.

used to think Marfa was a kind of practical joke that West Texans were playing on cultural elites. It’s remote even for Texas. The nearest airports are in El Paso and Carlsbad, New Mexico, each two hundred miles away. The landscape is okay if you like scrubby hills and plains of yellow grass. And yet aesthetes come from all over, lured by the minimalist vibe the place embodies.

Twilight Zone

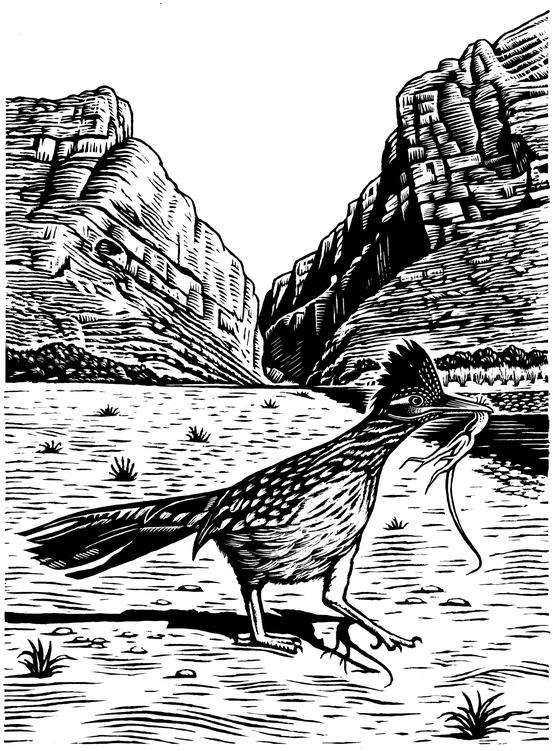

episode and something really strange is about to happen. One winter evening, when Roberta and I passed through town on our way to Big Bend, we saw a skunk sauntering down the sidewalk of the main street. He had the place all to himself. He affected an air of proprietorship as he navigated past the Hotel Paisano, where James Dean, Rock Hudson, and Elizabeth Taylor stayed in 1955, when they were filming

Giant

. During a classic West Texas hailstorm, Hudson and Taylor raced around with buckets to catch ice for their Bloody Marys. We lost sight of the skunk as he approached the pink wedding-cake courthouse in the center of town.

That night we drove east of town on U.S. 67 to see the Marfa Mystery Lights. Against the shadowed outline of the Chinati Mountains, odd yellow and white lights darted about, merging and dividing, disappearing, then reappearing seconds later in a different spot. They seemed to be dancing, which added to the air of enchantment. There have been numerous explanations—gas from petroleum deposits, optical illusions, electrical discharges from crystal formations—the most plausible being that they are reflected lights from the highway. James Dean was reportedly so fascinated by them that he bought a telescope. Your perceptions of what is real or at least normal get tested.

The artist Donald Judd rented a house in Marfa in 1971, “due in part to the harsh and glib situation within art in New York and to the unpleasantness of the city,” he wrote. He was also on the run from any form of government, and far West Texas was as close to anarchy as he could get. “I chose the town of Marfa (pop. 2,466) because it was the best looking and the most practical,” he wrote.

He wound up buying an abandoned army base that had been a detention center for German prisoners of war. There were a number of barracks and two massive brick sheds that had been used to repair tanks and artillery pieces. Judd filled the sheds with rectangular aluminum boxes of the exact same dimensions, differing only in the ways in which they are subdivided. One box is bisected by a vertical panel, another by a slanted panel at a sixty-degree angle, and so on—a hundred geometric variations on a single theme. The glare off the boxes made it difficult to see inside; it was like looking at water through the reflection of a bright afternoon.

Judd noted that as an artist he was primarily interested in space, and he designed this immaculate environment to eliminate the distraction of color or whim. He claimed to have invented the concept of an “installation,” by which he meant the use of an entire room to present his concept. The rectangular theme of the boxes was echoed in the etched-concrete floor, the coffered ceiling, the windowpanes, and even the weathered bricks. Looking through the windows at the bleached-out field, one sees larger, concrete boxes replicating similar choices. They are well made and dignified but also look like leftover shipping containers.

Roberta adores Donald Judd. “I appreciate the spareness and severity of the lines in concert with the spareness and severity of the surroundings,” she explained, as we wandered among the concrete boxes outside in the blinding sunlight, which Roberta called “an essential part of the art.” She was so caught up she didn’t notice the shimmering whipsnake sliding through the grass at our feet.

I admired the exactness of Judd’s enterprise, although it was hard to square his fixation on order with his anarchic politics, or the cultish following that has sprung up in the two decades after his death. When we checked into our hotel, there were Donald Judd books for sale at the front desk, and even bumper stickers asking WWDJD? What Donald Judd would do was a question I had never asked, but the Marfans were deeply interested in the answer.

We walked over to the new Robert Irwin installation, a U-shaped building. One wing is painted black, the other is white, and they are transected by scrims that filter the light. Rectangular windows at specific intervals admitted trapezoidal patches of sunlight onto the concrete floor. Through the windows I could see farmsteads and telephone poles. Doves were cooing. A piece of tin roof was flapping in the breeze. I wondered what art even was. Donald Judd in 1986: