Glacier National Park (3 page)

Read Glacier National Park Online

Authors: Mike Graf

The next day the Parkers got off to an early start.

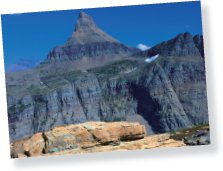

The road east of Avalanche followed McDonald Creek. Far above, a solitary peak spiked high into the air. Its snowfields glistened in the morning sun.

James stared at the picturesque mountain, then checked his map. “It’s Heavens Peak, I think.”

“How high is it?” Morgan asked.

“8,987 feet.”

Mom suddenly slowed down the car. “Well, if we have a little bit of heaven up there, look at what we have down here.”

Right in the middle of the road was a large, fresh-looking pile of bear scat.

“Hmm,” Dad pondered as he gazed into the forest. “I wonder how far away the culprit is.”

A large bird with a white head circled far above the marsh. It spiraled upward on the morning’s rising warm-air currents, gliding along until it spotted something below

.

The eagle slowly drifted down

.

Suddenly, it tucked its wings and quickly descended, landing on the limb of a tree

.

The bald eagle gazed at a jumbled mass of bones

.

The bird hopped from its perch and found a piece of stringy leftover tissue and tugged at it with its beak. The elastic tendon stretched out, causing the eagle to hop back. Finally, the meat ripped off the bone and the raptor devoured it

.

A raven landed a few yards away. It tilted its head sideways and eyed the carcass. The black bird hopped a few feet closer

.

The eagle squawked and spread its wings, then stared at the intruder

.

The raven hopped closer to the hoof of the calf, at the opposite end of the carcass. The smaller bird began pecking away at this part of the dead animal

.

Soon, another raven joined the feast

.

Mom slowed the car again. Two bicyclists were stopped ahead. They straddled their bikes as they peered forward.

Morgan saw why the cyclists were stopped. “Look, a bear!”

The black bear sat in the middle of the highway, far ahead of the riders. It stared at the two people, and they stared back.

Mom pulled up right behind the cyclists while Dad leaned out the window. “How long has it been there?”

One of the riders turned his head halfway. “We’ve been here about ten minutes, and it hasn’t budged.”

A car approached from the opposite direction. The black bear turned around and rambled into the forest.

The cyclists looked at each other. “I guess we should go now,” one said.

“But what if it’s right behind those trees?” the other replied.

Mom heard the conversation. “We’ll escort you,” she called out.

Mom drove slowly past the cyclists so they could follow. As the group crept by the place where the bear had disappeared, everyone peered into the woods, looking for the large animal.

After a few minutes, one of the cyclists gave Mom a thumbs-up sign. She waved to them and sped up, leaving the bikers behind.

The Parkers continued on, reaching a large bend in the road called The Loop. The road climbed steadily, Heavens Peak looming in the west.

James leaned forward from the backseat. “You can see the road up there.”

“All the way until the gap near the top,” Dad added. “Just like the road is heading toward the sun.”

CLIMBING TO THE SUN

Going-to-the-Sun Road is the main highway in the middle of Glacier National Park. It takes visitors up over Logan Pass and through some of the most spectacular scenery in the park. The road is named after nearby Going-to-the-Sun Mountain.

Up to eighty feet of snow can accumulate on Logan Pass, forming what’s called the Big Drift. Because of deep, late snows and poor visibility, the road takes about twelve weeks to plow in the spring. Logan Pass is usually open from mid-June to mid-October.

Before the road was finished in 1933, it took visitors three to four days to get across the park.

The road climbed on, hugging a cliff on the right. A small stone wall protected drivers from a long tumble should they accidentally veer off course.

Mom maneuvered carefully around a bend. “This is quite a road!” she exclaimed.

The family passed a long, continuous shower of water cascading onto the highway. “The Weeping Wall,” Mom announced, reading the sign.

Across the way, a plume of water fell below several peaks and snow-fields. The Parkers passed a sign pointing it out as Bird Woman Falls.

Morgan leaned forward. “Is that snow above the falls a glacier?”

“It’s hard to tell from here,” Dad replied. “Can you see what the map says, James?”

But James was staring at something far above. He studied the two distant objects until he saw one of them move. “There are two animals up there!”

Morgan tried to look out James’s window. “I want to see too.”

Mom took a quick peek then said, “I really need to keep an eye on the road.” She noticed a turnout ahead. Mom pulled over and the Parkers scrambled out of the car.

James pointed up the mountain. “There they are!”

The two animals were perched on a rock, gazing down on the road.

“What are they?” Morgan wondered aloud. “They’re light brown like some grizzlies, but much smaller.”

“Are they cubs?” James asked.

Dad grabbed the binoculars and focused on the animals. “I see,” he announced. “They’re not bears at all.”

Dad passed the binoculars to Mom. Mom took a look. “Marmots!” she exclaimed.

The Parkers gazed at the perched rodents. Just then, the two cyclists slowly huffed by. Dad noticed sweat dripping down their faces. “How’s it going?” he asked with concern.

“It’s quite a climb,” one of the riders replied between breaths.

“And we have to be at the summit before 11

AM

!” the other added.

“Do you need anything?” Dad asked.

“Thank you, we’re okay,” the first cyclist responded.

Dad got into the car and looked at his watch. “It’s 10:30,” he said. “I hope they make it.”

“Why do they have to be at the top by then?” James asked.

“The park wants all cyclists off the winding west side of the road by eleven because the traffic gets too heavy after that.”

The family piled back into the car, and Mom continued driving toward the summit. As she approached the cyclists chugging along, a car passed going the opposite direction. Mom slowed down, staying behind the riders. “There just isn’t any extra room on this road!” she exclaimed.

After the car passed, Mom inched by.

Morgan leaned forward and spoke to Dad. “Are you sure you want to ride this road?”

“I’m sure I want to try,” Dad replied. “I’m going to ride from east to west. There’s less traffic on that side of the park.”

The Parkers drove the last stretch before the pass. They passed a small parking area and a cascading waterfall. At the summit, several cyclists were dismounting their bikes. They leaned them up against a sign that said L

OGAN

P

ASS

6,646

FEET ELEVATION

. One of the bikers took a picture of their whole group.

Mom pulled the car into a crowded, busy parking lot, and the Parkers climbed out. James noticed the hazy, smoke-filled skies to the east. “It must be a huge fire,” he said.

The wolf lay among a series of tree roots deep in the forest. He licked his injuries again, but didn’t try to stand

.

Two squirrels scampered about in the forest nearby

.

A high-pitched call signaled some intended meaning from one to the other

.

One of the squirrels frantically dashed down the trunk of a tree. It scurried across the forest floor with the other running after it. The lead squirrel jumped onto the base of another tall pine. The two squirrels chased each other in circles, spiraling up the trunk until they reached the upper branches of the tree. One began nibbling a cone, dropping the shavings onto the forest floor. Soon the other was chasing after it again, both scampering down the tree and onto the ground

.

The scrawny, famished wolf kept still while staring at the unsuspecting squirrels as they ran right toward the carnivore. He tensed and waited, then pounced, landing with his paw on a squirrel’s back. The wolf pinned the squirrel down and bit off its back end, swallowing the whole chunk. The other squirrel dashed away, wailing, into the trees

.

The wolf chomped further into what was left of the squirrel. A few quick bites, and the whole animal was gone

.

The grizzly crossed an alpine region of grasses and tiny flowers along the Continental Divide. The bear rambled across a small, melting glacier

.

Eventually she meandered down from the alpine zone. Far below, a deep, cobalt blue lake glistened in the sun. The lake was dotted with small floating chunks of ice

.

The grizzly noticed people sitting on rocks near the lake. She gazed at them, watching for movement, then continued downward until she entered a forest filled with thick shrubs

.

A clump of red berries caught the bear’s attention. She wandered closer and lifted a paw to bend the shrub toward her. The grizzly opened her mouth and swallowed a cluster of tiny, sweet fruits. Then she stood up and searched around for more

.

The grizzly rambled from one buffalo berry patch to another, devouring as many of the delicacies as she could find. Then she paused from her feast and sniffed the air

.

Far below her were a sow and two cubs. The large bear watched them for several minutes as they, too, fed among clumps of bushes, then she dropped down and foraged for more berries

.

The Parkers joined a small group of people behind the Logan Pass Visitor Center. A ranger was standing on a rock, giving a talk. “Thousands of years ago, immense rivers of ice carved both sides of the park,” he said, then pointed east. “We know that because of the massive U-shaped valleys.

“And because of the glaciers’ impact,” the ranger continued, “the park was named after them. In the 1800s, there were at least 150 glaciers here. Now, due to climate change, less than 25 glaciers remain, and that number is quickly dropping.”

The ranger turned and looked at the mountain behind him. “Clements Mountain used to have one of those glaciers. But it expired around 1938. The current projection is that all of the park’s glaciers will be completely gone by around 2020. They are rushing to oblivion.

“But global warming affects more than glaciers. It can change meadows, raise tree line, and alter food sources for animals. And although it may be too late to save the glaciers here, we can all consider changing our habits to reduce pollution, which is heating up our atmosphere.”

The ranger ended his talk, then stayed around to answer some questions.

The Parkers began their journey toward Hidden Lake.

“So,” James said, “whatever glaciers we see on this trip, we may never see again.”

“Unless we come back real soon,” Morgan replied.

“I want to see as many as possible, then,” James announced.

“Me too,” said Dad.

The Parkers trekked up a series of wooden steps. Soon they approached a large mound of rocks near the foot of Clements Mountain.

On the way to Hidden Lake.

“There’s the old moraine from the glacier,” Dad realized. “It’s where the ice pushed the rocks before the glacier receded.”

The Parkers gazed at the alpine scenery. Wildflowers filled the meadows off the boardwalk. “Look at all the bear grass stalks,” Mom said. The tall white flower was splashed throughout the meadow.

“Are they named that because bears eat them?” James asked.

“More because they grow in typical bear habitat,” Mom replied.

The family looked around. A cascading stream tumbled down from the moraine. Nearby, a small patch of snow still clung to the ground. But there were no bears.

Soon the family left the boardwalk and began hiking on a dirt path. Morgan noticed a group of people peering toward some stunted trees. Several of the hikers had their cameras out.

A large white animal emerged from the shrubs. “A mountain goat!” Morgan exclaimed.

The large goat, whose fur was matted, walked slowly along. A smaller goat followed it. The adult turned and charged the smaller one, running right across the trail.

“Whoa!” Mom exclaimed as the wild animals brushed by.

The two goats slowed down by a clump of trees.

“Hey! Over there!” James exclaimed.

The other mountain goats were farther up. One was walking right on the trail. Dad watched it. “Those things have some seriously strong leg muscles,” he commented.

“I guess they need them to climb these mountains,” James said.

BORN TO CLIMB

Adult mountain goats are three to four feet tall and weigh between 150 and 300 pounds. They eat alpine grasses, flowers, hemlock trees, and shrubs. Mountain goats are well adapted to living on rocky cliffs. Their hooves have special pads that give the animals traction and prevent them from skidding. The pads act like suction cups on the rocks. A mountain goat’s hooves have hard, sharp edges surrounding a soft inner area. The two halves of a mountain goat’s hoof can move separately from one another. This helps the goat get a better grip while climbing.

Once the animals moved farther away, the family scurried by and came to a wooden platform overlooking Hidden Lake.

The Parkers gazed at the deep blue lake and the mountains all around it. Across the way was pyramid-shaped Reynolds Mountain. In the opposite direction, James noticed a slab of ice atop a peak in the distance. “I think that might be part of Sperry Glacier!” he exclaimed.

“Our first glacier sighting,” Morgan announced. “Although we can’t see much of it from here.”

They eventually made it down to a sandy area along the lakeshore. Mom and Dad passed around snacks. Morgan remembered her journal. She took it out and wrote:

Dear Diary:

I’m writing from Hidden Lake. We’ve seen a bunch of mountain goats along the trail, and a few minutes ago a mountain goat and its kid walked right up to the lake, about ten feet away from us! We watched them as they lapped up some water.

They were so close we felt bad. I know we aren’t supposed to be near the park’s wildlife. But it’s almost like they are tame. And they’re everywhere around here. I can even see tufts of their fur caught on some branches nearby.

I LOVE Glacier! I can’t wait to see some of the park’s glaciers up close.

Hopefully some of the smoke from the fires will be gone soon too, then we’ll get the deep blue skies we’re expecting.

Sincerely,

Morgan