Georgian London: Into the Streets (6 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

It wasn’t only vanity which claimed a proportion of the City’s

whalebone supply. A small but significant proportion of the population suffered with bone disease and hernia, making corsets an essential piece of everyday wear. Stays or corsets were also fashioned for the correction of scoliotic spines and dropped shoulders. Alexander Pope, who suffered with tuberculosis of the bone, wore one for most of his life.

As people grew richer, the trade boomed and the demand for whalebone grew. Most whaling ships pitched up at Howland Great Dock In Rotherhithe, later known as Greenland Dock, where the stench of rendering whale carcasses was not inflicted on the city. The dealers descended upon the ships and examined the catch, and the whalebone was removed for sale to warehouses near Three Cranes Wharf, where it was laid out carefully on the floor, with aisles between for the merchants to wander up and down and make their choice. Other floors held elephant ivory, cochineal beetles or natural sponges – all luxury items.

Once purchases had been made, they needed to be transported. London had a highly developed logistics system by the 1720s, run by the Guildhall, off Cheapside. All vehicles wanting to carry goods in the City of London had to purchase an annual licence which, when each part of it was added up, came to over £2. No driver was to be under sixteen years of age. A one-way traffic system operated in the Thames Street area to facilitate the loading of goods without chaos: the carts, when empty, had to enter it via one set of nominated streets, to the east, and exit via another set, when laden, to the west. One-way systems were in place by around 1720. Carts and wagons had ‘stands’ (just like taxi ranks today) where they were allowed to wait for work, and each employer had to take the first cart or wagon in the queue. Being overloaded was an offence, and long lists of what comprised a load – such as ‘

three bales of Aniseeds

’ or ‘six barrels of Almonds’ – give an insight into the goods being transported. ‘Three puncheons of prunes’ was a small load, and nineteen hundredweight of cheese a mere half-load. Any cart or wagon found unattended, or ‘standing’, resulted in a fine of five shillings for the first offence, ten shillings for the second and twenty shillings for every offence after that. Constant abusers would have their vehicle taken to ‘

the Green-Yard’, near Cripplegate, to be ‘impounded and kept, until the Owner thereof shall have paid the Penalty incurred, and the Charges of impounding and detaining every such Cart, Car, or Horses

’.

For smaller purchases, weighing up to 56lbs, licensed porters were on hand for hire. Strong, hardy men, they carried goods back through the streets. Two porters were permitted to carry double the weight; regular and often impromptu wagers were held to see how quickly they could make it to their destinations. Handbooks for shopkeepers and clerks were published with comprehensive entries of which carriers took goods where: goods could be sent to Chipping Norton through Powers at the White Horse, in Cripplegate, or to South Wales through Edwards at the Castle and Falcon, in Aldersgate. In 1768, twenty-two coaches per day left London for Bristol, all of them available to take small purchases and passengers. The detail involved in such tradesmen’s guides reveals the complexity and volume of the London commodity trade. As the century progressed, the guides became larger and more detailed as trade continued to grow. Yet the City’s rich trade in goods was being rapidly eclipsed by the trade in money itself.

Threadneedle Street is associated with the Bank of England and the Stock Exchange. But it also has a hidden history: it was home to both the French Church and one of London’s oldest synagogues.

The French Church was the church of the Huguenots, the Protestant people of France. As Nonconformists in a Catholic country, they had long been under pressure to convert. The Threadneedle Street Church was founded in 1550, when a group of Huguenot merchants arrived in London. They were Calvinists, coming predominantly from the educated classes, including the lower nobility. They banded together in communities that appear to have been based on similar interests and friendship, but they gave themselves a military hierarchy. Samuel Pepys described one of their relaxed services in 1662: ‘

In the afternoon

I [went] to the French Church here in the city, and stood in the aisle all the sermon, with great delight hearing a very admirable sermon, from a very young man.’ The Threadneedle Street Church burned down in the Great Fire but was rapidly rebuilt, and by the beginning of the Georgian age the descendants of the original founders were already powerful figures in the City.

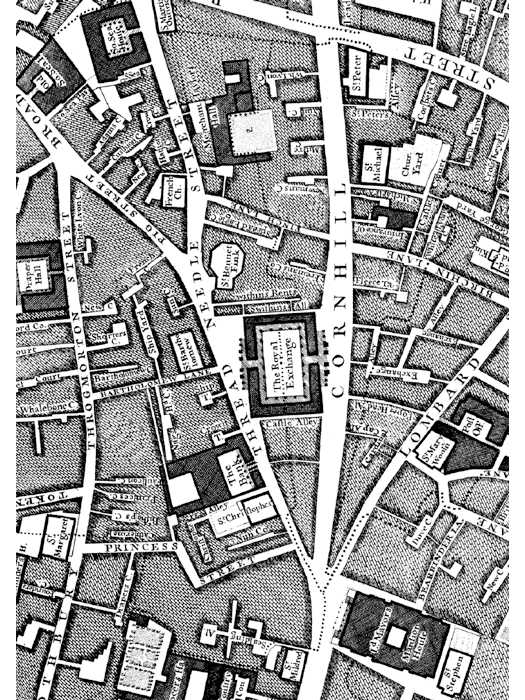

The Bank of England and Royal Exchange, showing the Mansion House, the French Church and South Sea House, detail from John Rocque’s map, 1745

Only a stone’s throw from the French Church, and right in the heart of what would become the financial district of the City, was a Sephardic Jewish synagogue. It was illegal to be Jewish in England after the Edict of Expulsion, passed by Edward I in 1290. Jews continued living in London, but in secret. Outwardly, they pretended to be Spanish Catholics but three ancient City synagogues remained active: Old Jewry, Threadneedle Street and Gresham Street.

On 17 December 1656, a group of openly practising Jews of London purchased a house in Creechurch Lane for a synagogue, with a total capacity of 85 men and 24 women. The following year, a piece of land was purchased at Mile End for a Jewish cemetery, the first Jewish broker was officially admitted to the Royal Exchange, and the first Jewish names appeared in the Denization Lists, akin to having an ‘indefinite leave to remain’ visa. The official admission into the Royal Exchange was little more than a token gesture, for people of all backgrounds and religions traded freely there: ‘

the Jew, the Mahometan

, and the Christian transact together … and give the name infidel to none but bankrupts’.

London’s early Jewish community was made up mainly of Sephardic Jews of Levantine descent, in small family units, often specializing in the trade of exotic goods. The Ashkenazi Jews of Germany and eastern Europe, who came later, comprised swathes of people from the very rich to the very poor, with larger families and a broader selection of vocations. In 1692, the Ashkenazim were present in large enough numbers to open a synagogue of their own in Duke’s Place, near Aldgate.

They termed themselves

‘the German Jews’ and saw themselves as distinct from ‘the Portuguese Congregation’ of the Sephardic Jews.

King William III had been ably assisted in matters of war and finance by Solomon de Medina who, in 1700, was the first Jew to be

knighted in England. When, in 1698, Rabbi David Nieto formed a committee to raise money for a new synagogue, de Medina was the largest contributor by a healthy margin. Some land in Plough Yard was purchased on a lease of sixty-one years for the Bevis Marks Synagogue. (Bevis Marks may sound like a person but it was the street Plough Yard opened on to, and was only a short distance from the Duke’s Place synagogue.)

On 12 February 1699, the committee signed an agreement with Joseph Avis, Quaker and builder, for the building of a synagogue on Bevis Marks at a cost of no more than £2,750, which is the equivalent of four and a quarter million pounds now. The Quakers were the largest Nonconforming religious denomination in the same area, traditionally living around Lombard Street. Queen Anne showed her approval of the collaboration by donating a roof timber – a symbolic gesture, corresponding with the Jewish requirement to maintain a head covering in the sight of God. In 1702, the Bevis Marks synagogue was dedicated. Avis returned all monies left over from the works, stating that he would not profit from building a religious house.

In 1723, a law was passed allowing Jews to hold title to land. This was a major step forward and led to the ‘official’ opening of a third synagogue, in Magpie Alley, Fenchurch Street, known as the Hambro synagogue. The Jewish Naturalization Act was passed in 1753, which meant that Jews could become naturalized English citizens after seven years in the country. It was dubbed ‘The Jew Bill’ and was repealed the following year due to massive street protests. Things calmed down, and London’s Jewish community carried on as before – commercially present, yet socially invisible.

Despite being marginalized citizens, who clung tenaciously to ‘foreign’ lifestyles, the French and Jewish communities of the City are crucial to the history of the Bank of England. Just as English monarchs had traditionally turned to Jewish moneylenders before the Edict of Expulsion, William III turned to some of London’s richest men in the early 1690s. He was waging a war in the Low Countries and was desperately short of cash. The Bank of England was founded in 1694, to supply this need, and became such a part of the British identity that

when the first commuter omnibus service started in 1829, running from Paddington to the City, its destination was given only as ‘The Bank’. These days, we have lost the definite article and the same destination, whether by bus or Tube, is known simply as ‘Bank’.

During the late seventeenth century, banks were private and it was up to the customer to choose which man he trusted enough to deposit his money with. Child’s Bank, Hoare’s and Coutts & Co., are three of the earliest and most famous. Their founders – Francis Child, Sir Richard Hoare and John Campbell – were all goldsmiths and bankers, used to buying in and storing quantities of bullion to fashion their wares. Their promissory notes were known as Running Cashes and functioned like a banknote. These men were prominent and trusted, but it was thought that London needed an official bank, such as those in Amsterdam or Germany.

A group of City merchants stepped up who believed they could raise a million pounds to start a new bank. A significant number of these men were Huguenots, including their leader, John Houblon, whose family had made their money in shipping. The million pounds would go to the state, and the newly created Bank of England was to reap £65,000 interest for its investors annually, and in perpetuity. Thus, in one swift Act of 1694, the National Debt was created.

In the chapel of Mercers’ Hall in Poultry, a Book of Subscriptions was opened for ten days at the end of June, allowing the citizens of London to invest in the new bank. At the end of this short period, 1,267 people had subscribed and Houblon was elected first Governor.

The Great Seal of the Bank bore the image of Britannia, with her spear and her leg boldly on show, which had appeared on the coins of Hadrian and Antoninus Pius in the second century

AD

. No more was heard of her until after the Restoration when, in 1667, Charles ordered a Britannia medallion to be struck to commemorate the Peace of Breda, which ended the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

His own likeness

, on the front, was captured from a drawing done by candlelight, by ‘Mr Cooper, the rare limner’, whilst John Evelyn held the candle. Charles decided that Britannia should feature on the reverse, and that the Duchess of Richmond should sit as the model. The reaction to the Duchess of Richmond was so positive that she began to

appear on the halfpennies and farthings issued soon after. As Samuel Pepys recorded, her face is ‘

as well done as ever I saw

anything in my whole life, I think; and a pretty thing it is, that he should choose her face to represent Britannia by’.

Two years later, during the Great Recoinage of 1696, Britannia came to symbolize the new standard of English money. Old, fake or clipped coins had become a huge problem. England had minted most of its coins in the Royal Mint near the Tower since around 1279, with the high-value denominations in gold and sterling-standard silver. These coins had a set value, but they stayed in circulation for a long time. Over the decades, the bullion prices changed, so the real value of the metal was either lower or higher than the face value of the coin. If the value was lower, it was cheaper to ‘buy’ coins and make them into silver dishes, spoons and forks than it was to buy the bullion to make them. So coins were removed from circulation. At the same time, the price of bullion on the Continent rose and clever merchants shipped English coin to Europe, where it was purchased and melted down. By the 1670s, John Evelyn recorded that there were not enough coins around to pay for simple household items and food. This provided the perfect opportunity for fakers. As long as no one looked too closely, and simply continued to pass the money around the system, it

was

worth the face value. Daniel Defoe always attempted to hand over any fake money first, but made sure he had the right amount of genuine money in his pocket in case he was caught. When nineteen-year-old Isaac Newton made lists of his ‘sins’, at Whitsuntide 1662, along with stealing, ‘

punching my sister’, ‘falling out with the servants’ and ‘having unclean thoughts’ was ‘striving to cheat with a brass halfe crowne

’. A less than promising start for the man who would become Warden of the Royal Mint. Passing off the fake coin was so widespread that the shopkeepers – who were supposed to destroy any fake coin that came their way – often passed it on, and a secondary trade in fake money sprang up alongside the bullion trade. The making of fake money was a skilled job: there were dies to carve, and striking coins from hard mixed metals was not easy.