Georgian London: Into the Streets (10 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

Delarivier Manley (1672–1724) was one of London’s first writers for a political party, but she wasn’t popular with everyone. Pope slammed her most popular work,

Secret Memoirs and Manners of several Persons of Quality, of Both Sexes, from the New Atalantis, An Island in the Mediterranean

, published in 1709, as a piece of transient scandal. In 1711, Manley decided she was retiring, tired of wading ‘

through Seas of Scurrility’ and ‘the Filth they have incessantly cast at me’. She didn’t retire, of course, and in 1714 – when again she wrote that she might give it all up, as politics was ‘not the business of a Woman

’ – she was also writing her six volumes of political allegories, six political pamphlets and another nine issues of the

Examiner

. Manley was a plain woman, unlucky in love and reclusive, but she carved out

a successful career in the masculine realm of political writing as queen of the Grub Street hacks.

Close to Grub Street was an unusual building which would house one of perhaps the most famous publications of Georgian London:

The Gentleman’s Magazine

. St John’s Gate, which had been built in 1504 as the house entrance to the Priory of the Knights of St John, is the traditional entrance to Clerkenwell from the south. The gate soon fell into secular use; in the early 1700s, it was Hogarth’s childhood home during the years when his father ran a coffee house there, after which Edward Cave took it on as a house. Cave began

The Gentleman’s Magazine

in 1731, featuring the gatehouse on the front of each issue. The magazine provided Samuel Johnson with his first regular writing job and went on to be one of the most influential ‘human interest’ publications of the eighteenth century. The gate was also where Johnson’s pupil and friend David Garrick gave his first theatrical turn in London.

For many years during the eighteenth century, part of the gate also served as the local watch house, and Clerkenwell seemed to have more than its fair share of prisons, with the Clerkenwell Bridewell, New Prison and later Coldbath Fields. Land was cheap and the proximity to the Old Bailey meant it was convenient. The space available in Clerkenwell was also attractive to trades such as furniture making, which required workshops as well as storage space. Those who employed large numbers, such as metalworkers, watch- and clockmakers, also found Clerkenwell very suitable for their purposes, and soon a large artisan community was built up around the Green, where Fagin and the Artful Dodger taught Oliver Twist to pick pockets.

Local metalworkers included silversmiths, such as the Bateman family, headed up by the matriarch Hester who after the death of her husband, in 1760, pulled herself up from being an illiterate widow to a formidable businesswoman. Her workshop represented the zenith of small family firms during the eighteenth century.

Metalworking, clockmaking and cabinetmaking are trades which

used piecework from the earliest times, and required plenty of both natural light and water. The clock- and watchmaking trades, in particular, required men to turn out small parts, usually the same one over and over again, with great precision. The piecework system meant they were paid according to how many they produced. Others were responsible for the assembly, and eventually it was only the employer’s name which was engraved or stamped on the mechanism and case.

In 1798

, of the 11,000 men living in Clerkenwell, 7,000 were watchmakers.

John Harrison, the man who created the first reliable marine chronometer and solved the longitude problem in 1761, took up residence first in Clerkenwell’s Leather Lane and then in Red Lion Street, just to the west. Here he worked tirelessly, with the help of the government, to produce a timepiece which would accurately place a ship at sea. Harrison’s overriding and long-term obsession was often regarded as something of a joke, but his work enabled British ships to undertake vast journeys with confidence. Despite his borderline reputation Harrison contributed immeasurably to securing the British Navy’s dominance of the oceans during the Age of Sail.

ALL MANNER OF GROSS

AND VILE OBSCENITY’ IN HOLBORN

Holborn was one of London’s oldest roads, and much of it escaped the Great Fire. The large houses built in the Tudor period for merchants wanting to leave the City smoke had long since been divided into apartments leased by students at the Inns of Court, or poorer families clubbing together for the rent. The underworld which had occupied the Holborn Valley (where the Viaduct stands now) was forced out by the Fleet River improvements, and began to move west. Other residents included the brothel keepers of Chick Lane, and taverns of the lowest sort. Men who were happy to pay for their company could obtain partners both female and male, and the Holborn area was known for its gay subculture.

The Georgian period in London saw the development of modern gay sexuality. Men and women identified themselves as homosexual

and succeeded, to varying degrees, in establishing a network of friends, acquaintances, locations and establishments which served their sexual needs. The ‘

typical homosexual

of the eighteenth century was a respectable tradesman rather than a fashionable libertine’, and the vast majority of people who lived gay lives in London were ordinary men and women.

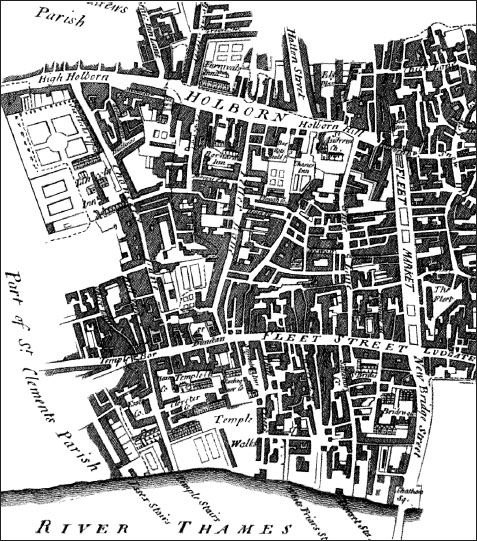

Holborn, Lincoln’s Inn and Temple, showing the Fleet Market built over the Ditch, and The Fleet prison, detail from John Royce’s map, 1790,

The Buggery Act, as it was known, had been passed in 1533 by Henry VIII, making the ‘detestable and abominable Vice of Buggery

committed with mankind or beast’ punishable by hanging. It was, however, rarely brought to court. After the Restoration, literature on the act of sodomy proliferated, largely due to licentious poetry by the new breed of libertines, such as John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester. ‘Sodomy’ became taboo – the act of the debauched and diseased – and just as there were groups which protested against the low morals of the theatres and alcohol, the Society for the Reformation of Manners was established in 1690. The group went around forcibly shutting pubs, taverns and coffee shops on Sundays. By 1701, there were almost twenty spin-off societies in London. They set up a network of busybodies known as Reforming Constables, four in each ward of the City, and two in each parish outside. It was their responsibility to act as hubs of knowledge, finding out information about those who offended decency and keeping a tally of evidence. These ‘

sly reforming hirelings

’ rose to have a quasi-legal power within the community, and it behoved everyone to keep on their right side. Their first victim was Sea Captain Edward Rigby, in 1698, who had picked up a young man at the fireworks on Bonfire Night and was later entrapped by the boy and members of the Society. Rigby was sentenced to stand in the pillory at Charing Cross and Temple Bar. He also had to pay a fine of £1,000 and spend a year in prison, but he was not executed.

By the early eighteenth century, the Society was actively targeting gay cruising grounds. In 1707, in a ten-day campaign, they succeeded in arresting over forty men suspected of being active sodomites. The fear of accusation created a brisk trade for blackmailers, who ingratiated themselves with their targets before informing them that they would report them to the Society if they did not pay up.

At the same time, molly houses had become a fixture of the London male gay scene. They were essentially pubs or taverns catering for a gay clientele rather than gay brothels, although sex often took place on the premises. During the 1720s, there were at least twenty active molly houses in London. In February 1726, on a Sunday evening, the constables gathered for a raid on the molly house of one Margaret, or ‘Mother Clap’, in Field Lane, Holborn. Margaret Clap was married to John Clap, who ran a nearby pub but rarely visited her coffee house. In many rooms of the coffee house were beds for the use of the clientele,

at a price, although they all made use of the large central room for drinking and dancing to fiddle music. There was also a ‘

marrying room’, where men could be ‘blessed

’ before having sex.

In the early hours of that Monday morning, forty homosexual men were arrested, taken to Newgate and held for trial. Significantly, none were discovered having sex, although some were found in a state of undress. For those arrested, there were fines, imprisonments, time to be spent in the pillory and three hangings. The raid on Mother Clap’s house was prompted by a customer-turned-informer, Mark Partridge, who had fallen out with his lover and who decided to take the Society on a tour of London’s molly houses. The prosecutions themselves were facilitated by a thirty-year-old prostitute named Thomas Newton. Newton decided to visit Mother Clap in gaol to pay her bail. There he was apprehended by two constables who coerced him into becoming an informer. It appears there were few corners of gay London Newton was not familiar with, and he was very effective for the Society, particularly when used as a familiar face to entrap men cruising in Moorfields, along Sodomites’ Walk.

William Brown, the married man apprehended by his penis, was indignant at being arrested and responded to questioning with, ‘I did it because I thought I knew him, and I think there is no Crime in making what use I please of my own Body

.’ His defence echoed the words of the philosopher John Locke, who posited that, ‘

Though the earth

, and all inferior creatures, be common to all men, yet every

man had a property in his own person: this no body has any right to but himself.’ Despite Brown’s high-minded assertion of his right to use his own body as he wished, he was sentenced to stand in the pillory, where he was pelted with rotten eggs, dead cats and turnip tops.

The men involved with the trials of 1726 were working men: cow keepers, a milkman, an upholsterer, an orange-seller. Around half were married or were known to have fathered children, but a clear minority were self-identifying prostitutes or practising homosexuals. The trials brought homosexuality out into society. It may not have been discussed in ‘polite’ company, but there was no getting away from it. On 7 May 1726, the front page of the

London Journal

featured an exposé of London’s major cruising grounds:

… the nocturnal Assemblies of great Numbers of the like vile Persons at what they call the Markets, which are the Royal-Exchange, Moorfields, Lincolns-Inn Bog-houses, the South Side of St James’s Park and the Piazzas of Covent Garden, where they make their Bargains, and then withdraw into some dark Corners to

indorse

, as they call it, but in plain English to commit Sodomy.

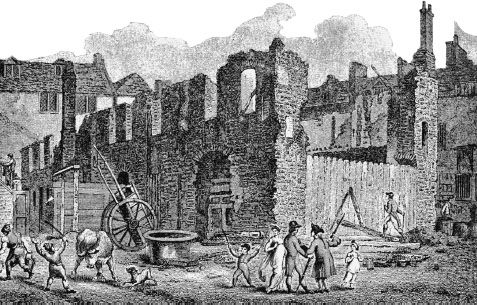

The remains of Gibbon’s Tennis Court off Vere Street, Lincoln’s Inn, after the fire of September 1809

The societies died out in the 1740s, as the fashion for moral reform faded, but towards the end of the Georgian period the Holborn area saw one last gay scandal with the White Swan affair. The White Swan was a tumbledown pub in Vere Street, now obliterated by Kingsway. It stood near Gibbon’s Tennis Court, an old real tennis court which had become an increasingly down-at-heel theatre. The area was edgy, with most of the residents taking advantage of the cheaper, older housing.