From the Forest (12 page)

Authors: Sara Maitland

Rumpelstiltskin

Once upon a time there was a funny little man and he was dancing in the forest.

He, at least, called it dancing, though to you it might have looked more like gambolling and frolicking, tumbling and prancing, because he was not graceful. He danced in the hazel coppice and he looked like those trees – short and bristly with skinny misshapen branches. But, like those trees, he promised sweetness and ripeness and generous joy. Later, in the moonlight, high up the mountainside, he danced with trembling aspens and the bristly junipers and he looked like them too – solitary, clinging to the poor soil, spindly and grotesque. He was leaping and somersaulting and singing for joy:

Today I’ll brew, tomorrow I’ll bake

And soon I’ll have the Queen’s namesake;

Oh how hard it is to play my game

For Rumplestiltskin is my name.

He is me. I am him.

And he ought to be the hero of this story, but they have made him into the villain.

Once upon a time there was a greedy king and a boastful, ambitious – though admittedly rather lovely – miller’s daughter.

He wanted to be rich and she wanted to be queen. They were as selfish and worldly and mean-hearted as each other, and they lied and tricked and exploited their inferiors to get what they wanted.

They ought to be the villains of this story, but they have made themselves into the heroes.

It is not fair.

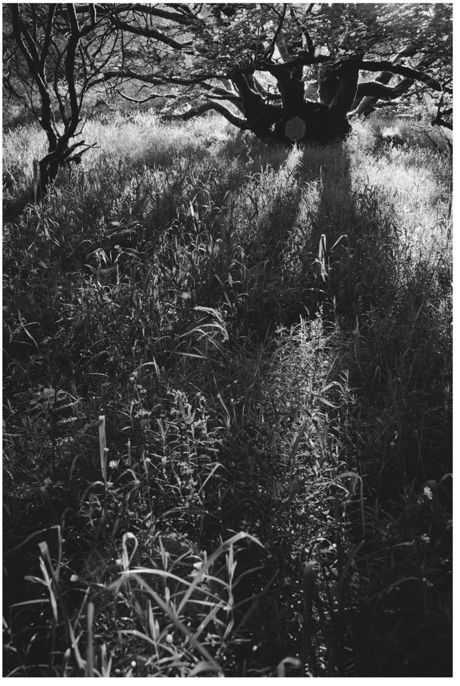

The funny little man was dancing in the forest because there no one could see him dance, or so he thought. In the forest he was hidden. In the forest there were no sneers, no averted glances, no stifled giggles or covert disgust. In the forest there were no mirrors. In the forest he could be who he chose and how he wished. He was full of joy that night. He danced because, come morning, he was planning a good deed, and in his folly he imagined that a king and queen would be grateful, would smile at him and would let him play with their darling baby. Poor fool.

He was me. I was him.

It is not fair. So I am going to tell the story again – it is my story and I have the right.

Once upon a time there was a self-important miller; he had worked his way up from not much and wanted all the world to know it. He scrooged his workers, bullied his wife and spoiled his children, as such men do. His favourite child was his oldest daughter, who was very like him only prettier, and on her his ambition was set. Nothing was too good for that little madam. She grew up wonderfully self-centred and with a total lack of useful skills; she believed the world owed her not simply a living but adulation and chocolates and jewels and furs. Her father, who inevitably called her ‘my princess’, believed that she ought to be a queen, and by the time she was seventeen she entirely agreed with him.

The miller was a man who could not help boasting. Swagger was like sweat for him, it oozed out of his flesh and smelled slightly rank, although he never noticed, any more than he noticed that his childhood friends laughed at him and that his new acquaintances despised him. His voice was loud and his purse was full – what more could a man need? he thought complacently.

One day the miller met a king – a venal, greedy young man with sharp eyes, a weak chin and a rather unimportant kingdom, but a real and proper crowned king nonetheless. In an expansive mood brought on by brandy and arrogance, the miller told the king that his daughter could spin straw into gold.

Well, the king was not stupid, or at least not very stupid, and he was both eager for gold and somewhat dubious, as anyone might be. He did what kings have tendency to do when something they want a lot looms up on their horizons – he sent some soldiers round to arrest her and drag her off to his castle. This was not, of course, quite what the miller had intended, but he was convinced that the mere sight of his daughter would melt the King’s heart, and any form of introduction to royalty tends to rot the good sense of men like him. So he managed to fool both himself and her that this was not an arrest exactly, but more of an invitation to visit the castle. He gave her a good deal of advice, which would have been shrewd if he had not failed to understand that the King was more driven by avarice than by lust. A surprising number of men are, when push comes to shove, but this is often hidden by the fact that avarice can easily enough take the form of greed for power and power can most easily, and pleasurably, be expressed by sexual conquest. So the miller accompanied his daughter to town and, more in a spirit of investment than of generosity, bought her some rather exotic lingerie and some very expensive jewellery.

Yes, these are nasty people and my take on them is without good humour or kindness. Or even much forgiveness. But I am just a funny little man who dances on his own in the high forest and dreams that one day someone will love him. I have cause for bitterness, as you will see.

So, the young woman arrived at the palace with an eager anticipation. Her father had, of course, failed to inform her fully of his folly, so she was little startled to be led not to a lavish bedchamber where some appropriate minion would help her decorate herself for the festivities, but to a small, cramped attic filled with straw, in which there stood a spinning wheel. The King accompanied her and announced:

‘Now get to work; and if all this straw isn’t gold by morning, I’ll have you executed.’

A humbler, more sensible and more merry-hearted girl would have laughed at the King, admitted she had not the least idea how to set about such a task and told him that indeed she could hardly spin flax or wool into thread, let alone straw into gold, and that her father was a boastful fool and the King an idiot for believing him. But after the haughty looks she had cast at her sisters and the contemptuous flounce with which she had crossed the village square, accompanied by a guard of uniformed soldiers, she could not face the shame. She smiled archly at the King, hoping to deflect him, and was still smiling flirtatiously when he left the room and slammed the door. When she heard the key turn in the lock her smile collapsed, and before many minutes had passed she was weeping.

When she looked up there was a funny little man looking at her sympathetically. He enquired politely as to her difficulties.

He is me. I am him.

At this point I did not know she was a nasty piece of work. Passing about my business in the corridor, I had heard someone crying and popped my head round the door to see if I could help. No magic about that – the King had left the key in the keyhole. There was this pretty little thing, her face all swollen with tears, and anyone would have offered to help if he could.

Now, most people have forgotten this, but spinning straw into gold is not that hard: there is a knack to it and it takes practice, but anyone with the will can learn. It is easier with straw than with many things because it is the right colour to start with. You sit at the spinning wheel and you think of all the golden things in the forest: of lichens in flat, round disks on granite; of wild narcissus under the first fresh leaves in springtime; of the patterns on the back of

Carterocephalus palaemon

, the Chequered Skipper butterfly; of globe flowers seen through hazel branches, bright as sunshine; of the stripes of a bumblebee sipping on clover; of the iridescence on the undersides of dung beetles; of the flash of goldfinch in a hawthorn hedge; of chanterelles on shaded moss; of owl eyes blinking in the deep wood; of tormentil and asphodel and agrimony and broom; of horse chestnut leaves in autumn and of ripening crab apples; of grass seed heads catching the low sun in winter. If memory fails, even buttercups and dandelions will do, though the work is slower with such common joys. You gather all these together in heart and head and eye and then – and this is the tricky bit – you need to spin the spinning wheel very, very fast and without breaking the rhythm.

Whizz, whizz, whizz. Whirr, whirr, whirr.

And that is it really, though of course a loving heart helps, as always.

After the straw was all spun into gold, the miller’s daughter asked the funny little man, ‘What must I pay you?’ He wanted to ask for a kiss, but he was courteous and gentle, so he asked for her necklace and she gave it to him.

The King, of course, was too greedy to let it go at that. A whole room filled with gold thread was not enough for him, so he dragged her off to another larger attic and all three of them went through the same process

Whizz, whizz, whizz. Whirr, whirr, whirr

. This time the funny little man wanted to ask for a hug, but he was gentle and courteous, so he asked for her ring and she gave it to him.

She was so pretty and grateful that the funny little man was glad to have been of service to her.

But the third night was different. The King had been thinking, and although he despised her for being a miller’s daughter, his enthusiasm for the gold overrode his snobbery. He said that if she would spin one more roomfull he would marry her. And far from refusing point blank, she agreed. Her snobbery overrode her good sense. She was happy to marry a king who would make her a queen, even though he had proved himself venal, greedy and cruel.

Not just folly, wicked folly. The funny little man was shocked. He thought he would teach her a lesson. So he slipped into the room and spun the straw to gold.

Whizz, whizz, whizz. Whirr, w hirr, w hirr.

And when she enquired what she would have to pay him this time, he asked for her first child. He thought that would give her pause, but after a bit of pouting and grumbling she agreed. She promised.

He never imagined she would consent; he never meant to take the child.

He wanted to make her think and he wanted to do a gracious thing. He wanted someone to be grateful to him – not laughing or sneering but grateful, admiring even, and appreciating. That is not a big ask, surely.

I do know.

He is me. I am him.

So they made a deal and a year later he learned that the Queen was safely delivered of a child and he came back. He thought he would pretend to take the child, though he never would do so really. He had earned it, but he would not claim it – and she would be grateful and would smile at him and would let him play with the baby. He had it all planned.

She reneged on the contract. She promised, she promised and she did not come through. She was a liar and a coward and a suspicious, selfish woman.

He gave her one more chance: he offered to play a game with her. She had to guess his name. She cheated, flourishing the riches that she had stolen from her own husband and sending spies to catch the little man dancing in the forest.

He did not want her baby. Unlike her, he was kind and gracious and generous. He only wanted a chance for the world to see those things in him and be glad and grateful. He knew that babies need their mummies and do not need to be stolen away by funny little men who everyone laughs and sneers at.

There are rules; there are rules in fairy stories:

• The true queen is gentle and kind and good as well as beautiful.

• Hard work is rewarded – magical hard work by those who live in the forest is especially rewarded.

• The old, the ugly and the weak should be respected, treated tenderly and not mocked.

• Promises must be kept.

So why is the funny little man the villain, and the greedy king and the spoiled queen the heroes?

It is not fair.

I should know.

I am he. He is me

.

4

June

Epping Forest

L

ate in June, and despite getting lost in the strange mixed countryside of tiny sunken lanes, motorways and approaches to Stansted Airport, I rather surprisingly managed to arrive in time at Bishop’s Stortford railway station, where I met Robert Macfarlane, the writer of

Mountains of the Mind

,

Wild Places

and

The Old Ways

, off a train from Cambridge so that we could go and walk in Epping Forest.

We drove south from Bishop’s Stortford and crossed under the M25 to approach the forest from the north. There is something pleasing about the idea that one of the largest areas of ancient forest in England is

inside

the M25, and therefore effectively part of London. In fact, the city and the forest have an intimate, mutually beneficial relationship: the city grew because there were forests (providing fuel) around it, and Epping Forest survived because of the city.

In the 1130s most of what is now Essex, including Epping Forest, was declared Royal Forest by Henry I and was indeed used by the monarchs for hunting.

1

As in other Royal Forests, the interests of the Crown, landowners and local inhabitants were managed under the Forest Law, and over the next couple of centuries the commoners (those who held common rights in the forest) established the usual arrangement of rights to wood cutting and, in this case most significantly, to ‘intercommonage’ – the right to graze stock throughout the whole forest, not merely within the manor where they lived. By the eighteenth century there was a considerable tradition of hostility between the landowners and the commoners. For example, here the rule was that landlords owned the maiden, or timber, trees, but that the commoners could cut wood from pollards for fuel. There are frequent accounts of landlords bringing complaints to the forest courts that maidens had been lopped and thus turned into pollards. Equally, the commoners were actively resistant to all attempts to limit free grazing, even those legally sanctioned by the Verderers (the local officers of the Forest Law); they tore down all new fences and attacked the workmen constructing them.