Freedom's Children (4 page)

Read Freedom's Children Online

Authors: Ellen S. Levine

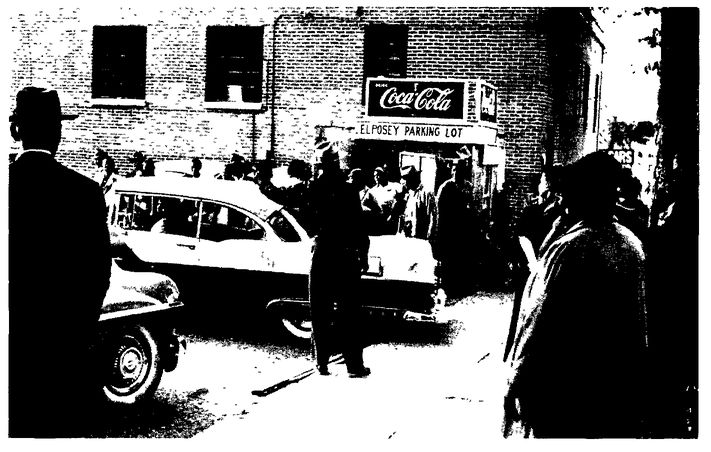

Facing page:

Waiting for a car pool during the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama.

Waiting for a car pool during the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama.

2 â The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Beginning of the Movement

The modern civil rights movement is often said to have started with the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56. For over a year, nearly fifty thousand blacks in Montgomery stayed off the buses. They walked, hitchhiked, carpooled, all in protest against the discriminatory and demeaning system of segregation.

In Montgomery, black riders were about seventy-five percent of all bus passengers. Still they had to give their seats to any standing white person, or stand themselves over empty seats in the “white only” area.

Jo Ann Robinson was a teacher at Alabama State College and head of the Women's Political Council, a group of black professional women. E. D. Nixon was past president of the Montgomery NAACP, a Pullman porter, and an active member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Both had urged a bus boycott for many years. They waited only for the right moment.

On December 1, 1955, a forty-three-year-old seamstress named Rosa Parks, who had worked as secretary at the local NAACP, was arrested and charged with violating the segregation laws for refusing to get up and give her bus seat to a white person. The night Rosa Parks was arrested, Robinson and some friends printed thousands of leaflets calling for a one-day boycott. The leaflet read:

Another Negro woman has been arrested and thrown in jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down. It is the second time since the Claudette Colvin case that a Negro woman has been arrested for the same thing. This has to be stopped. Negroes have rights too, for if Negroes did not ride the buses, they could not operate. Three-fourths of the riders are Negroes, yet we are arrested, or have to stand over empty seats. If we do not do something to stop these arrests, they will continue. The next time it may be you, or your daughter, or mother. This woman's case will come up on Monday. We are, therefore, asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial. Don't ride the buses to work, to town, to school, or anywhere on Monday. You can afford to stay out of school for one day if you have no other way to go except by bus. You can also afford to stay out of town for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don't ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off of all buses Monday.

Monday morning the buses rolled through the black neighborhoods empty. The boycott was virtually total. Fueled by the success of the one-day action, thousands at a church meeting that night voted to continue the boycott. The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) was organized to coordinate boycott activities. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the new young pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, had recently moved to Montgomery from Atlanta, Georgia. An eloquent speaker who was willing to assume additional responsibilities, he was elected president of the MIA. The Montgomery Bus Boycott thus began not only the civil rights movement, but also Dr. King's remarkable career as a world-famous leader of that movement.

Some Montgomery segregationists were violent in their response to the bus boycott. Reverend Ralph Abernathy was a boycott leader with Dr. King. His home and church were bombed. Dr. King's home was also bombed, and so was that of community leader E. D. Nixon. Even with these attacks, the success of the boycott inspired similar protests in other southern cities and towns. Black ministers throughout the South whose churches had supported the boycott established a new group that became the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) with Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., as president. SCLC, with other civil rights groups, was a main organizer of protest activities in the 1960s.

Rosa Parks has been recognized as a hero of the movement for her determined resistance to discrimination that began the Montgomery Bus Boycott. But a careful reading of that first boycott leaflet shows that before Rosa Parks there was Claudette Colvin.

Claudette Colvin was fifteen years old in 1955. On her own she defied the segregation laws on the Montgomery city buses when she refused to give up her seat to a white person. She was arrested, found guilty, and fined. Nine months after Claudette's arrest, the boycott began. Claudette Colvin was ahead of her time.

When I grew up, the South was segregated. Very much so. Your parents had taught you that you had a place. You knew that much. In the city you had the signs. You have to stay here, you have to drink out of this fountain, you can't eat at this counter. I thought segregation was horrible. My first anger I remember was when I wanted to go to the rodeo. Daddy bought my sister boots and bought us both cowboy hats. That's as much of the rodeo as we got. The show was at the coliseum, and it was only for white kids. I was nine or ten.

It bothered me when I got old enough to understand. You could buy dry goods at the five-and-ten-cent stores, Kressâs, H. L. Green, J. J. Newberry's. You could buy, but you couldn't sit down and eat there. When I realized that, I was really angry.

Certain stores you couldn't try on the clothes. You could just ask for what you wanted. I remember this girl in school. She was mulatto. We used to get her to go in Nachman's to try on hats for us. Because she was white-looking, they didn't know. We had one friend whose father had money. So if she saw a hat or shoes at Nachmanâs, she used to push this girl to go in and get it. We knew this girl could pass, and we just wanted to be able to say that somebody with black blood has been in there to try on a hat or a pair of shoes. This was before the boycott.

At that time we were rebelling in different ways. I was always rebellious, but my mother said this is the way it is. The white people, they own everything, they bought everything, they built itâyou know the whole story. That made me angry.

I talked about it with my friends. We would say the older people let white people get away with it. They never said they didn't like it. Older black people were always respectful to the white people. ut the younger blacks began to rebel.

Â

In school we were always taught that we had to study hard. We had to learn and think twice as hard as a white person in order to get ahead. You must be educated. I went to Booker T. Washington. When I was in the ninth grade, my history teacher was always discussing current events.

Most of the schoolteachers at Booker T. Washington came from Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Dr. Martin Luther King was pastor. And most of them got their education in the North. I think they were just pricking our minds to see how we were thinking.

My mind got pricked. This history teacher was tall and real dark. She'd say, “I'm a real African. I'm a pure-blooded African.” We really didn't know what she was talking about. She was the blackest teacher in the school. In those days we would size up people by the color of their skin.

“How could she stand up there saying these things?” we used to say. She kept pricking our minds. “Do you feel good about yourself, you feel good inside? What do you hate about yourselves? Are you studying hard?” And she'd say, “You won't let anything bother you and stop you, regardless of your complexion.” She tried to get that in our minds. She said there's no such thing as good hair. We were worried about good hair.

We had to write essays about how we felt about ourselves. And in those days when a teacher told you to do something, you had to do it, whether you wrote one line or more.

I wrote I was an American. My essay was that I felt clean, and I didn't see why we couldn't try on clothes in the store. I said I wasn't going to wear a cap before I tried on a hat. In those days you had to wear a cap or a head scarf to try on a hat so that “grease” wouldn't get on the hat. And I said furthermore, why do we have to press our hair and have to straighten our hair to look good?

The teacher read my essay before the class. Everybody said, “Oh, Claudette! You're crazy. You'll never get a boyfriend.” And my closest friends said, “Claudette, would you really come to school with your hair kinky?” Well, the teacher really had pricked my mind, so I went home and I washed my hair and I didn't straighten it. My sister and my mother said I was crazy. When I came into school, everybody said I was crazy. I looked like a six-or seven-year-old. I had my hair in little braids all over. When you're thirteen, you don't wear your hair in all those braids. Maybe two.

My other sister had died not too long before, and they all said I was upset because she had passed. I said no. It was the essay I wrote. They all had said I wouldn't have the nerve to do that to my hair, and that I was just joking. Or that I was trying to get a good grade. But I wasn't joking. I actually did it. And I did lose my boyfriend. Teenagers figure you must be crazy if you'd lose your boyfriend. But that was okay. He said, “Claudette, I didn't believe that you would come to school this way.”

I kept wearing it like that, and they kept me out of school plays. Everybody at school had heard about my braids. I wore them until I proved to them that I wasn't crazy. I had to convince them that I wasn't crazy.

Claudette became aware of civil rights as a public issue with the arrest of Jeremiah Reeves.

At my school the reason we got into it was because a boy named Jeremiah Reeves was arrested for supposedly raping a white woman, which he did not do. The authorities kept him in jail until he came of age, and then they electrocuted him. He was from Booker T. Washington, my school. He was the drummer for the school band. His father was a delivery man at the same store that Rosa Parks worked at. I was in the ninth grade when it happened. And that anger is still in me from seeing him being held as a minor until he came of age.

That was the first time I heard talk about the NAACP. I thought it was just a small organization. I didn't know it was nationwide. I heard about it through the teachers. Some people said that the reason they convicted Jeremiah was to prove to the NAACP that they couldn't take over the South. Our school would take up collections for the NAACP, and we'd have movies for Jeremiah to try and help pay for good lawyers for him. Our rebellion and anger came with Jeremiah Reeves.

Â

At that time, teenagers didn't like to ride the special school bus too much. If you had to stay after school for band practice or a rehearsal, or hang around for after-school activities, and you missed the special, you still could ride on your school pass, but on the regular bus.

On the regular buses there were signs on the side saying “Colored” with an arrow this way and “White” with an arrow this way. The motorman could adjust the signs. He could direct people to sit where he wanted them to.

You knew that you weren't supposed to sit opposite a white person, or in front of a white person. The number of seats varied in different communities. Depending on whether there was a larger black population, there could be the first two or four rows reserved for white people.

On March 2, 1955, I got on the bus in front of Dexter Avenue Church. I went to the middle. No white people were on the bus at that time. It was mostly schoolchildren. I wasn't thinking about anything in particular. I think I had just finished eating a candy bar. Then the bus began to fill up. White people got on and began to stare at me. The bus motorman asked me to get up. We were getting into the square where all the buses take their routes in either direction. A colored lady got on, and she was pregnant. I was sitting next to the window. The seat next to me was the only seat unoccupied. She didn't realize what was going on. She didn't know that the bus driver had asked me to get up. She just saw the empty seat and sat next to me. A white lady was sitting across the aisle from me, and it was against the law for you to sit in the same aisle with a white person.

Other books

La felicidad es un té contigo by Mamen Sánchez

Hungry Heart: Part Two by Haze, Violet

Shattered Destiny: A Galactic Adventure, Episode One by Odette C. Bell

The Sweetest Hours (Harlequin Superromance) by Parry, Cathryn

Dark Lady by Richard North Patterson

Healing my Heart: Book 2 - My Heart Series by Michelle, Aleya

Sons of God's Generals: Unlocking the Power of Godly Inheritance by Joshua Frost

Executed at Dawn by David Johnson

The Secrets of the Shadows (The Annie Graham series - Book 2) by Helen Phifer

My Favorite Midlife Crisis by Toby Devens