Freedom's Children (19 page)

Read Freedom's Children Online

Authors: Ellen S. Levine

The regular Democratic Party in Mississippi was lily white, and everybody knew that. Black folk had not been allowed to vote except for the mock election we had had. Going to the convention was an attempt to put the nation on the spot. At the very least, we could ask Johnson to do what we thought was right, which was to unseat the regular Mississippi Democratic delegation and to seat the MFDP.

I don't think we felt that was actually going to happen, but just going through the process itself was good. It would give us an opportunity to participate in the political process at a level that we had not participated in before, at least in recent times.

All these civil rights workers were there, all around the boardwalk just interacting with people. We couldn't get inside because we didn't have tickets. So we camped out on the boardwalk. There were speeches going on all the time. I remember Stokely Carmichael giving a speech out there. It was almost like a pep rally to keep the spirit up, to keep people's eyes on the prize.

The Credentials Committee at the Democratic Convention refused to seat the MFDP instead of the all-white state Democratic Party. The committee proposed a compromise plan that MFDP rejected.

I was hearing those political sophisticates saying, “Let's take something, because something is better than nothing.” And I heard Fannie Lou Hamer saying, “Let's not do this.” I was so proud of the stance that Mrs. Hamer took. I think she was just right on target, and I was very proud that she was unwilling to compromise. While I understood that there were forces saying this was politically naive, from the standpoint of pride and the movement and the people, I thought she was absolutely correct. So I didn't think it was a sad moment at all, not for me personally.

Â

The movement shaped me in a way that I wouldn't have been shaped otherwise. I look at some of my classmates that went through school the same time I did. While some of them may have made it materially and have “good jobs,” making fairly decent salaries or in their own business, I get a sense, when I sit around and talk to them, that there's a space there. There's a void, a kind of emptiness. I can always focus back and say I'm glad I was part of that process.

Other experience was important, but not equivalent to the movement that I was engaged in from â62 through '65. It's almost as if everything else is a footnote. There was a sense of mission, a sense of correctness, a sense of change. Not only were we transforming ourselves and our lives, but we were also transforming the lives of our parents. My father and mother went on to vote. My father eventually ran for alderman in Holly Springs. He did not win, but he ran. My father wouldn't have dreamed of that in the sixties. My brother is now vice mayor of Holly Springs. It's because of those changes. It's because of the risks people took.

Following page:

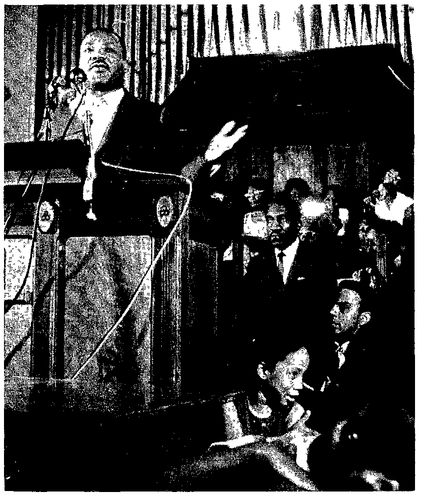

Sheyann Webb listens to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., preach

Sheyann Webb listens to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., preach

7 â Bloody Sunday and the Selma Movement

In 1965 the civil rights battleground shifted to Selma, Alabama, a former slave market town, about fifty miles from Montgomery. Nearly half the voting-age population in the Selma area was black, but only one percent was registered to vote. That meant some 150 blacks were registered out of about 15,000 who were eligible.

Black people repeatedly attempted to sign up at the county courthouse, but were as repeatedly turned away and sometimes arrested by Sheriff Jim Clark and his police “possemen.” As in most other southern towns, when blacks were allowed to take the tests, they were seldom passed.

In the early sixties, local activists and SNCC volunteers set up voter registration workshops. Sheriff Clark would harass them, sending officers to meetings to record the names of those who attended. Then he'd release the names to newspapers in the hope that the civil rights “agitators” would be fired from their jobs.

In the mid-sixties SCLC workers began to organize in Selma. Their goals were twofold: desegregate stores and other public facilities, and register voters. Young activists from nearby Montgomery came to help. Sixteen-year-old Princella Howard went to Selma with James Orange from the SCLC staff in late August 1964. She has a vivid memory of that event:

I can remember driving into Selma at night. It was dark. Ooh, I remember how black dark it was. The SCLC office had heard there was a movement starting there. They wanted us to see if it looked like something vital enough that we could work around the issue of voting rights and build a movement.

We went to SNCC's office, which was already set up, to see what they were doing and what they thought. They said this was the next place ... this is it!

Then we went to a church meeting. It was as black as could be outside, but when that church door swung open and we went in, it was like a bright light. I could see a glow in that church. It was the most unusual night. It was as bright and fired up in that church as it was dark outside. Whatever these people are praying for, they got it. That's how I looked at it. It was a-moaning and a-groaning, and it was some deep prayer going on in that church.

In January and February 1965, Martin Luther King came to Selma. Every day SCLC organized marches to the courthouse and to downtown stores, and every evening television news covered the mass arrests. When Dr. King was arrested, he observed that “there are more Negroes in jail with me than there are on the voting rolls.”

One evening Reverend C. T. Vivian of SCLC spoke at a mass meeting in nearby Marion, Alabama. As the audience left the church for a nighttime march, police troopers and a local mob attacked the crowd. Many people were wounded, including news reporters. Twenty-seven-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson, a native of Marion, was fatally shot while trying to protect his mother from a beating by state troopers. He died eight days later.

Dr. King spoke at Jackson's funeral. He said that Jackson had been murdered by police “in the name of the law,” by politicians who feed their listeners “the stale bread of hatred and the spoiled meat of racism,” by a government that wouldn't “protect the lives of its own citizens seeking the right to vote,” and by “every Negro who passively accepts the evils of segregation and stands on the sidelines in the struggle for justice.”

Reverend James Bevel of SCLC called for a fifty-mile march from Selma to the capital in Montgomery to protest Jackson's murder and to demand full voting rights for blacks. Alabama governor George Wallace opposed the march; a demonstration protesting a police killing would receive national news coverage and would be bad publicity for Alabama. He announced that state troopers would block the march.

The march organizers did not back down. On Sunday morning, March 7, 1965, hundreds left Brown Chapel, unofficial headquar ters of the Selma movement. They headed for the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where they were met by state troopers and local police. The marchers never got out of the Selma city limits. The troopers viciously beat them in a police riot that came to be known as Bloody Sunday.

Television stations all over America interrupted their local programs to show footage of the police riot. President Johnson said at a news conference, “What happened in Selma was an American tragedy.” Later, in an address to Congress, the president asked for passage of a voting rights act, saying, “Their cause must be our cause, too. Because it's not just Negroes, but it's really all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.” He ended his speech with the words of the civil rights song: “We shall overcome!”

After Bloody Sunday, Dr. King made a national appeal, asking clergy from around the country to come to Selma to join a second march. Not only clergy answered the call. Thousands of people, white and black, poured into the city. They slept on couches, floors, anywhere there was room. SCLC went to court to seek an order preventing Governor Wallace from stopping the second march. When the court finally ruled in favor of the marchers, President Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard, thereby placing them under federal, not state, government control, and sent two thousand U.S. army troops, one hundred FBI agents and one hundred federal marshals to line the highway route to protect the marchers.

Princella Howard was attending college in Iowa at the time of Bloody Sunday. As president of the college and youth division of the Iowa NAACP, she was sent back home to join the second march.

When I was on the train coming from Sioux City, there were loads of young ministerial white students on that train. As we got closer to Montgomery and I realized that they hadn't gotten off, the exchanges started. When I found out that they were coming to the Selma march, I got so excited. I said, “Show me who you're going to talk to and what numbers you have to call when you get there.” The man pulled out his purse and guess whose phone number it was? Mine! I said, “That's my mother!” MIA had only so many phone lines, and all of a sudden all of these people from all over the world were coming. So they opened up private phones on the street nearby. Ours was one of the first ones they used because of course we had been in the movement all of our lives.

You can imagine how excited I was. You see, the movement was my life. When I had to go away to college, it was one of the hardest things I've ever doneâto break away from the movement. It was a real strong family in the movement. Even now I don't think anybody who was outside the movement really realizes it. They were very strong, powerful cords. I mean, once you're in, you're in for life.

Thousands gathered on the morning of March 21 at Brown Chapel in Selma. They walked during the day and camped at night along the highway until they arrived four days later at St. Jude's school grounds in Montgomery. That night they held a big rally with entertainers Harry Belafonte, Tony Bennett, Joan Baez and others. Gladis Williams, a high school student, worked in the Montgomery Improvement Association office preparing for the arrival of the marchers from Selma.

I was on the MIA welcoming committee. We had to register all the people who were coming into town. They were coming from all over the nation, so we had a housing committee assigning them to homes. A lot came down to be in Montgomery when the march arrived here, and a lot of them went on to Selma to go on the march. We were collecting blankets and food for the marchers.

The day of the march, the school principal locked all the doors and all the windows because kids were jumping out of the windows trying to get to the march. I didn't go to school that day. It's important to go to school, but it was also important during that time for us to deal with the different problems that were here in Montgomery. It was just something we had to do.

When the marchers arrived from Selma, we were there to greet them. Thousands were there. Joy! That's what you felt. They stopped at St. Judes, and that's where they camped out that night. They had come fifty miles, but when you're marching and singing, it doesn't faze you how far it is.

The next day at least twenty-five thousand people marched through the city to the steps of the capital. A delegation from the group presented a petition to an aide of the governor, demanding an end to voting rights restrictions.

Delores Boyd was in the tenth grade. “It was just glorious walking down Dexter Avenue. There were troopers, folks on horses, and whites who were taunting. But there were so many black folk and white folk who joined the march. It was just such a lovely sight.”

But there were sacrifices along with the triumph. Both blacks and whites were killed. The first to die had been Jimmie Lee Jackson. Then James Reeb, a white minister from Boston who had answered Dr. King's call for clergy volunteers, was clubbed to death by a group of whites as he and his companions left a restaurant in Selma. At the end of the second march, there was a third killing. Viola Liuzzo, a white homemaker from Detroit, had seen the Bloody Sunday police riot on television. She then drove down to Selma to participate in the demonstrations. On Thursday, March 25, at the end of the rally in Montgomery, she drove marchers back to their homes in Selma. On a return trip to Montgomery, a carload of Klansmen spotted her Michigan license plates. They pulled alongside her on the highway and shot her through the car window.

Mary Gadson, from Birmingham, recalls the reaction of the community:

When Viola Liuzzo was killed, it was like she was a part of the family. I never knew her more than her name and that she was a Freedom Rider. But even today she's like a part of the family. That's just how much unity there was. During that time I believe she was a part of all black families. She really became kinfolks because she was involved. Her race didn't make a difference. To me she was a human being who was concerned, who had a heart, and who gave her life for what she believed in.

The sacrifices were not empty losses. Barbara Howard, who organized her Montgomery classmates to join the Selma marchers when they reached the capital, said:

The Selma murders were a real sadness. How could people take a life? They could see that they were losing the battle. They could see at this point we were halfway home. From 1955 up to 1965 a lot of ground had been covered and a lot of momentum had been built. So it only strengthened us. They didn't know that through the murders they actually helped to bring about the change faster than it would have come. And the nonviolence on our part moved it more smoothly.

Other books

Feral Park by Mark Dunn

Chicken Soup for the Cat & Dog Lover's Soul by Jack Canfield

Star Crusades Nexus: Book 03 - Heroes of Helios by Michael G. Thomas

The Panic Room by James Ellison

An Alpha for the Demigod by Ezra Dawn

Hunter: MC Romance (Hell Reapers MC Book 1) by Liz Lorde

Castillo's Fiery Texas Rose by Berkley, Tessa

Judgment Night [BUREAU 13 Book One] by Nick Pollotta

The Billionaire Dating Game: A Romance Novel by Aubrey Dark

Red Ink by Julie Mayhew