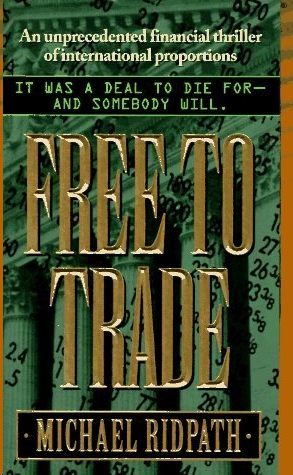

Free to Trade

| Free to Trade | |

| Michael Ridpath | |

| (1994) | |

| Rating: | ★★★☆☆ |

| Tags: | Fiction, General, Mystery Detective Fictionttt Generalttt Mystery Detectivettt |

From Publishers Weekly

Ridpath's first novel is a junk bond of a financial thriller, flashy but insubstantial. Trouble comes to narrator Paul Murray, rising bond trader at a small London firm, when one of his colleagues drowns in the Thames. The cops think accident or suicide, but Paul thinks murder, having seen the dead woman's brutal ex-lover molest her just before her death. So Paul starts sleuthing, pursuing leads in London, Manhattan and Arizona and tying the killing into a grand fraud involving a top New York trading firm. At the center of the fraud lurks an icy villain whose manipulations get Paul fired and placed under suspicion of insider trading-and murder. The villain isn't the brutal ex-lover, though, whose main purpose here is to perform gratuitous acts of violence that stick out from the main story like pickles on pudding; instead, the villain is, despite Ridpath's efforts to confound, exactly whom most readers will suspect halfway into the tale-which also suffers from leaden dialogue and myriad coincidences. Ridpath paces matters briskly, conveys the cutthroat ambience of the markets and, along the way, provides a solid seminar in venture capitalism. But anyone interested more in good fiction than high finance will find this offering a bad bargain. 100,000 first printing; $150,000 ad/promo; audio rights to HarperAudio; author tour.

Copyright 1994 Reed Business Information, Inc.

From Library Journal

A tale of corporate intrigue, Ridpath's first novel is acceptable if not exceptional. Paul Murray is a young ex-Olympian working as a novice securities trader for a London firm. Suddenly, he finds himself investigating a colleague's death, a multi-million dollar investment fraud, and threats to his life and livelihood. The novel moves well, effectively communicating the addictive thrill of high finance, and the ending is compelling. But some of the writing is naive and trite. Briticisms, such as the overused whilst, will grate on American readers, and some of the book's dialog is stilted. However, an aggressive marketing campaign is promised, and public libraries may face demand for this title.

--Rebecca S. Kelm, Northern Kentucky Univ. Lib., Highland Heights

Copyright 1994 Reed Business Information, Inc.

MICHAEL RIDPATH spent eight years as a bond trader at an international bank in the City of London. He was brought up in Yorkshire, graduated from Oxford University with a first class degree in history and now lives in North London with his wife and two daughters. This is his first novel.

FREE TO TRADE

By

MICHAEL RIDPATH

Copyright (c) 1995 Michael Ridpath

ISBN HB 0 434 00170 8

Version 1.0

CHAPTER 1

I had lost half a million dollars in slightly less than half an hour and the coffee machine didn't work. This was turning into a bad day. Half a million dollars is a lot of money. And I needed a cup of coffee badly.

The day had started off well enough. A quiet Tuesday in July, at the investment management firm of De Jong & Co. Hamilton McKenzie, my boss, was out. I yawned as I reread the

Financial Times

's tedious descriptions of yesterday's non-events. The dealing desks around me were more than half empty; people were away either on business or on holiday. Phones and papers lay scattered across abandoned desktops. Chaos at rest. The office felt like a library, not a trading room.

I looked out of the window. The tall grey buildings of the City of London pointed silently upwards out of the listless heat of the streets below. I noticed a kestrel gliding around the upper reaches of the Mercantile Union Insurance building a hundred yards to the west. The great financial centre slumbered on. It was difficult to believe anything was happening out there.

A solitary light flashed on the telephone board in front of me. I picked up the phone. 'Yes?'

'Paul? It's Cash. It's coming. We're doing it.'

I recognised the broad New York accent of Cash Callaghan, the 'top producer' at Bloomfield Weiss, a large American investment bank. The urgency in his voice pulled me up in my chair.

'What's coming? What are you doing?'

'We're bringing the new Sweden in ten minutes. Do you want the terms?'

'Yes please.'

'OK. It's five hundred million dollars, with a coupon of 91/4 per cent. Maturity is ten years. It is offered at 99

.

The yield is 9.41. Got that?'

'Got it.'

The Swedes were borrowing $500 million through the means of a eurobond issue. They were using Bloomfield Weiss as underwriter. It was Bloomfield Weiss's job to sell the bonds to investors; the term 'euro' meant that it would be sold to investors all over the world. It was my job to decide whether to buy it.

'Nine forty-one per cent is a good yield,' Cash went on. 'Ten year Italy yields 9.38 and no one thinks Italy is as good as Sweden. Canada is a better comparison, and that's yielding 9.25. It's a no-brainer. This one's going to the moon, know what I'm saying? Shall I put you down for ten million?'

Cash's enthusiasm to make a sale was extreme at the best of times. When he had $500 million of bonds to sell, it knew no bounds. He had a point though. I tapped some buttons on my calculator. If the yield on the new bonds did fall to the level of Canada at 9.25 per cent, that would mean the price would move up from 99 to 100. A nice profit for any investor quick enough to buy bonds at the initial offer price. Of course if the issue was a failure, Bloomfield Weiss would have to lower the price until the yield was high enough to attract buyers.

'Hold on. I've got to think about this one.'

'OK. But be quick. And you should know we have already placed three hundred million in Tokyo.' The phone went dead as Cash rushed on to his next call.

I had very little time to gather information and make a decision. I punched out the number of David Barratt, a salesman at Harrison Brothers. I repeated what I had heard from Cash and asked David what he thought of the deal.

'I don't like it. It sounds good value, but remember how badly the World Bank issue that was launched two weeks ago did? No one's buying eurobonds at the moment. I don't think any of my clients in the UK will touch it.' David's clear unhurried tones carried the weight of experience and a sound analytical mind. He had built up a loyal following of customers by being right most of the time.

'That's very useful. Thanks,' I said, and hung up.

Another light flashed. It was Claire Duhamel, a persuasive French woman who sold bonds for Banque de Lausanne et Geneve, known as BLG.

'Hallo Paul, how is it with you? Are you ready to buy some bonds from me today?' Her low throaty accent was carefully designed to demand the attention of even the hardest-hearted customer.

That morning I had no time for Claire's line of flirtatious chat. Although she did her best to hide it, she had excellent judgement, and I needed her opinion quickly. 'What do you think of the new Sweden?'

'Bof! A dog. A howling dog. I hate the market at this moment. So do my customers. So do my traders. In fact, if you want any, I am sure they will be offering bonds very cheaply.'

She meant that her traders disliked the issue so much that they would try to sell bonds as soon as the issue was launched, in the hope that they might buy them back cheaper later.

'Bloomfield Weiss claim that most of the deal has been placed in Tokyo already.'

Claire's reply was tinged with anger. 'I'll believe that when I see it. Careful, Paul. A lot of people have lost a lot of money believing Cash Callaghan.'

For the next few minutes the board in front of me flashed constantly as salesmen called in to discuss the deal. None of them liked it.

I needed to think. I asked Karen, our assistant, to put off all the incoming calls. I liked the deal. It was true that the market was very quiet. It was also true that the World Bank issue of two weeks ago had fared poorly. However, there had been no new issues since then, and I had the feeling that investors did have cash waiting for the right bond issue. And this could be the right one. The yield was certainly attractive.

Most intriguing was the Japanese angle. If Cash was right and they really had already sold $300 million of a $500 million issue in Japan, then the deal would go very well. But should I trust Cash? Wasn't he just taking me for a sucker; a twenty-eight-year-old with only six months' experience in the bond market? What would Hamilton do if he were here?

I looked around me. I supposed I should really discuss it with Jeff Richards. He was Hamilton's deputy and responsible for the strategic view the firm took on currencies and interest rates. But he liked to do things based on thorough economic analysis. Trading a new issue was not his cup of tea at all. I looked over to his desk. He was tapping figures from a booklet of statistics into his computer. Best to leave him out of it.

Apart from Karen, the only other person who was in the office was Debbie Chater. Until recently she had been involved in the administration of the funds managed by the firm. She had only moved on to a trading desk in the last two months, and had even less experience than me. But she was sharp, and I often discussed ideas with her. She sat at the desk next to me, and had been watching what was going on with interest.

I looked at her vaguely, searching for a decision.

'I don't know what the problem is, but suicide isn't the answer,' she said. 'You look like you are about to jump out of a window.' Her broad face split into a grin.

I smiled back. 'Just thinking,' I said. I briefly explained what Cash had said about the new Sweden, and the lack of enthusiasm from his competitors for the deal.

Debbie listened closely. After a moment's thought she said, 'Well, if Cash likes it, I wouldn't touch it with the proverbial bargepole.' She tossed me a copy of the

Mail.

'If you really want to gamble our clients' money away, why don't you do it on something safe like the four thirty at Kempton Park?'

I threw the paper in the bin. 'Seriously, I think there might be something in this.'

'Seriously, if Cash is involved, drop it,' she said.

'If Hamilton were here, I am sure he would get involved,' I said.

'Well, ask him. He should be back at his hotel by now.'

She was right. He had spent the day in Tokyo talking to some of the institutions whose money our firm managed. He should have finished his meetings by now.

I turned to Karen, 'Get hold of Hamilton. He's at the Imperial, I think. Hurry up.'

I still had a couple of minutes. It took Karen only one of them to track Hamilton down at his hotel.

'Hallo, Hamilton. I'm sorry to disturb your evening,' I said.

'Not at all. I was just catching up with some reading. I don't know why I bother. This so called "research" is all drivel. What's going on?'

I outlined the deal and repeated the negative comments of David, Claire and the others. I then told him what Cash had said about the Japanese.

After a few seconds' pause, I heard Hamilton's soft, calm voice with its mild Scottish intonation. Like a good malt whisky it soothed my nerves. 'Very interesting. We might have something to do here, Paul, laddie. I spoke to a couple of the life-insurance companies this morning. They both said that they were worried about the stockmarket in America and have been selling shares heavily. They have several hundred million dollars to put into the bond market, but have been waiting for a big new issue so that they can buy the size they want. You know how the Japanese are; if two of them think like this, then there are probably another half dozen with the same idea.'

'So maybe Cash was telling the truth?'

'Extraordinary as it may seem, that might be the case.'

'So shall I buy ten million?'

'No.'

'No?' I didn't understand. From what Hamilton had said, it looked as though this deal was going to work.

'Buy a hundred.'

'A hundred million dollars? Are you sure? It seems an awful lot of money to invest in a deal that nobody likes. In fact it seems an awful lot of money to invest in any deal. I'm sure we don't have that much cash available.'

'Well, then sell some other bonds. Look, Paul. Just once in a while we get the chance to make some real money. This is it. Buy a hundred.'

'Right. Will you be at the hotel for the rest of the evening?'

'Yes, but I've got some work to do, so don't disturb me unless you really have to.' With that, Hamilton hung up.

Buying $100 million was a big risk. A huge risk. If we got it wrong our losses would ruin our performance for the whole year. It would be very difficult to explain this to the institutions that trusted us with their money. On the other hand, if the Japanese really had bought $300 million, and we bought $100 million, that would leave only $100 million for the rest of the world. Hamilton had a reputation for occasionally taking large calculated risks, and getting them right.