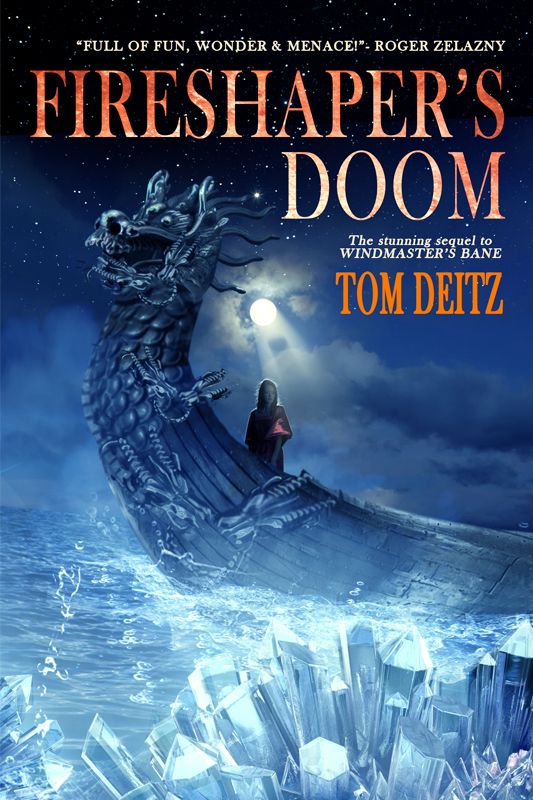

Fireshaper's Doom

Chapter III: The MacTyrie Gang

Chapter IX: The Irish Horse Traders

Chapter XII: In the Green Tent

Chapter XIII: The Wrath of Lugh

Chapter XV: Water, Fog, and Fire

Chapter XVII: The Room Made of Fire

Chapter XXIII: From Trail to Track

Chapter XXV: The Ship of Flames

Chapter XXVII: Boogers in the Woods

Chapter XXIX: The Burning Road

Chapter XXXII: Curses and Vows

Chapter XXXIII: The Well of the Bloody Strand

Chapter XXXVIII: A Debate in the Night

Chapter XXXIX: Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Chapter XL: A Sudden Change of Fortune

Chapter XLV: The Secret of the Sword

Chapter XLVI: Cause and Effect

Chapter XLVII: The Hounds of the Overworld

Chapter XLVIII: Fireshaper’s Doom

Chapter L: Coffee and ’Shine and Syrup

Fireshaper’s Doom: A Tale of Vengeance

By Tom Deitz

Copyright 2014 by Estate of Thomas Deitz

Cover Copyright 2014 by Untreed Reads Publishing

Cover Design by Tom Webster

The author is hereby established as the sole holder of the copyright. Either the publisher (Untreed Reads) or author may enforce copyrights to the fullest extent.

Previously published in print, 1987.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to your ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

This is a work of fiction. The characters, dialogue and events in this book are wholly fictional, and any resemblance to companies and actual persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Also by Tom Deitz and Untreed Reads Publishing

Windmaster’s Bane

for all the folks of Madoc’s Mountain

once and future

near and far

and for Maggie who made the buttons

Acknowledgments

Jared Vincent Harper

Gilbert Head

Margaret Dowdle Head

D. J. Jackson

Adele Leone

Chris Miller

Klon Newell

Vickie R. Sharp

Brad Strickland

Sharon Webb

Wendy Web

Fireshaper’s Doom

A Tale of Vengeance

Tom Deitz

Prologue: The Horn of Annwyn

Tir-Nan-Og, where Lugh Samildinach rules the youngest realm of Faerie, is a bright land—brighter by far than the dreary Lands of Men that float beneath it like a mirror’s dull reflection. Its oceans shine like liquid silver; its deserts sprawl like lately molten gold. The very air imparts a gleam to field and forest, man and monster. Even the Straight Tracks take on a sharper glitter there—at least those parts that show at all as they ghost between the Worlds like threads of tenuous light.

But a thousand, thousand lands there are, linked by the treacherous webs of those arcane constructions. And some are less idyllic.

Erenn, that mortal men call Eire, is one such country. Finvarra holds court there in his ancient rath beneath the hill of Knockma, king of the greater host of the Daoine Sidhe. Erenn’s sky is much more sober; its air not nearly as clear. It rubs along the Mortal World at an age more distant than its fellow to the west, yet the smoke of human progress still seeps through at times to grime the Faery wind with soot and the smells of death. Sometimes, too, the awkward, eager clatter of some man-made invention breaks the Barrier Between to haunt the Fair Folk at their feasting. Finvarra smiles but seldom.

And there is Arawn’s holding: Annwyn of the Tylwyth-Teg, which humankind name Cymru. If Tir-Nan-Og is early morn, and Erenn afternoon, then Annwyn is twilight. By day the sun looks veiled and dusty; at night lamps made by druidry shine brighter than the moon. Shadows tend toward purple there; the sky ofttimes takes on the hue of blood. The wind is not always gentle. And the borders are not clear—for in spots the very ground simply fades until it will support not even a spider’s passing. Many of the Straight Tracks end in Annwyn, or else lead into places where even the Elemental Powers merge and fragment endlessly like the dreaming of the damned.

* * *

“Will you go with me to Annwyn?” Lugh asked Nuada Airgetlam one morning. “If we do not visit Arawn’s court ere the Mortal World unfreezes, we may find no chance again for many ages.”

Nuada’s dark eyes narrowed with suspicion. “And what has fueled this sudden haste, my master? What difference can

their

weather make to us? The Walls Between the Worlds make cold no danger; and as for the Road, no ship of man can pass there, whatever be the season.”

“Leif the Lucky has beached his boats near the red men’s north-most holding,” the High King told his warlord. “Winter may hold them yet awhile, but spring will bring them south and westward. Tir-Nan-Og is safe at present, for my Power is great, and the glamour I have lately raised is strong. But I fear our time of peace will reach an ending, once word of Leif’s good fortune spans the ocean. Soon, I think, we must set watch on our borders!”

Nuada sighed his regret. “I too fear men’s coming and the tools of iron that always travel with them. But it is a thing that was bound to happen. You are right about Annwyn, though: if we would leave Tir-Nan-Og unguarded, we must start the journey eastward very shortly.”

And so, on a day when snow sparkled bright on the Lands of Men, and Leif the Lucky sang of Vinland and the kingdom he would carve, Lugh Samildinach and Nuada Airgetlam took the Golden Road across the sea and came to Arawn’s kingdom.

The Lord of the Dim Land received them well and feasted them for many days. Deep grew the bonds among the three, and diverse were the pleasures the three lords shared—in hunting and in trials of arms, in the savoring of song and poetry and subtle arts of women, and most particularly in the study of wondrous objects strangely fashioned.

“There is one thing left in Annwyn I would show you,” Arawn said one evening. “But I would not reveal it here.”

“And what might that thing be?” Lugh asked his host.

“We will ride out on the morrow,” Arawn answered, and no more would he tell them.

And so, in the shallow light of dawn they journeyed forth: Lugh astride his great black stallion, black hair bound by a fillet of gold, black mustache stirring in a west-blowing wind, gold silk surcoat shimmering loose above tight black leather; and fair-haired Nuada beside him in white and silver, his left arm clothed in creamy satin, the other a shoulder-stub forever cased in shining metal; and showing them the way, Arawn himself, in dark gray velvet and blue-tinged bronze. No banners flew above that riding, no trumpets marked its passage. Arawn’s squire alone went with them: a sullen, tightmouthed Erenn-lad whom the Dark King had in fosterage. Ailill was his name, though some already called him Windmaster—and in bringing him along that day Arawn was very foolish, though how much so would not be clear for nearly a thousand mortal years.

They rode all day, and at dusk were riding still.

At sunset they found themselves on a cold, black-sanded plain, so near the tattered fringe of Annwyn that even a nearby Track showed as nothing more than a smear of sparkling motes, like brass tilings strewn across the ground. A solid sheet of clouds hung low above them; before them was a country Arawn liked but little and the others not at all. A dead-end, blind pocket of a place, it was; open to nowhere else save Arawn’s kingdom: an ill-lit land where gray mist twisted in evil-smelling whirls among the half-seen shapes of stunted trees and shattered, roofless buildings.

It was a place of mystery and rumor, shunned even by the mighty of the Tylwyth-Teg. Powersmiths lived there: the Powersmiths of Annwyn, some folk called them, though they did not name Arawn their master, and Arawn was not so bold as to set any claim upon that race at all.

But the Powersmiths made marvelous things—things the Sidhe could neither craft nor copy nor understand, and it was just such an object that was the cause of the riding that day.

Arawn drew it from his saddlebag and held it out for Lugh’s inspection. A small hunting horn, it seemed, wrought of silver and gold, copper and greenish brass. At its heart was the curved ivory tusk of a beast that dwelt only in the Land of the Powersmiths and was near extinction there. Light played round about it, tracing flickering trails among the thin, hard coils that laced its surface. Nine silver bands encircled it, the longest set with nine gems, the next eight, and so on: nine black diamonds, and eight blue sapphires, seven emeralds, six topazes in golden mountings, five smooth domes of banded onyx, four rubies red as war, three amethysts, a pair of moonstones. And at the end, on a hinged cap that sealed the mouthpiece: a fiery opal large as a partridge’s egg.

“It is the most precious thing in all my realm,” the Lord of Annwyn told them. “Most precious and most deadly.” His gaze locked with Lugh’s, and he paused to take a long, decisive breath. “I would make you a gift of it.”

“A gift—but not without some danger, it would seem,” Lugh noted carefully.

“You are a brave man,” Arawn continued. “But you are also prudent, much more so than I. It would be best that you have mastery of this weapon.”

Nuada cocked a slanted eyebrow. “Well, if there is more to it than beauty, then it keeps its threat well hidden.”

Arawn nodded. “The Powersmiths made it. One of their druids set spells upon it—and then he died. It was meant as a pledge of peace, but now I dare not trust it.”

“It does not look much like a sword,” Ailill interrupted. “Does it hold some blade in secret that perhaps I have not noticed?”

“It cuts with an edge of sound, young Windmaster,” came Arawn’s sharp reply. “But perhaps it is best that I show you.”

The Lord of Annwyn gazed skyward then, to where a solitary eagle flapped vast wings beneath the red-lit heavens. “Behold!” he whispered, as he thumbed the opal downward, raised the horn to his lips, and blew.

No sound resulted—or at least no sound that even Faery ears could follow. But their bones seemed at once to buzz within them, and the hair prickled upon their bodies. The solid flesh between felt for a brief, horrifying moment as though it had turned to water. For an instant, too, the air seemed about to shatter in the wake of that absent noise.