Fighter's Mind, A (22 page)

Authors: Sam Sheridan

THE EGO IS GARBAGE

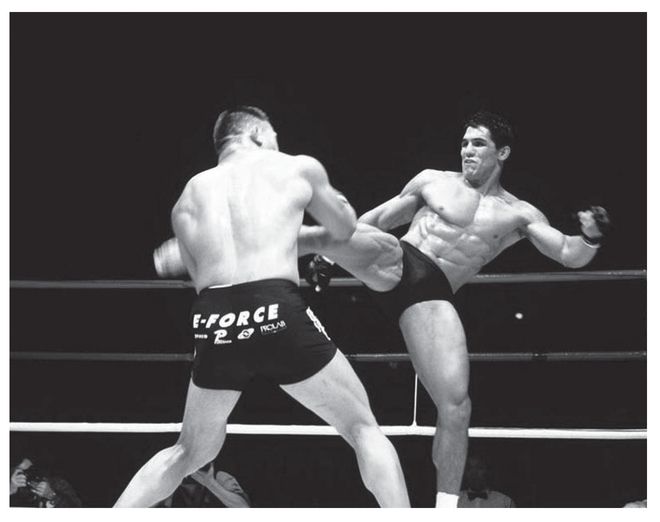

Frank Shamrock

What is a good man but a bad man’s teacher?

What is a bad man but a good man’s job?

If you don’t understand this, you will get lost,

However intelligent you are.

It is the great secret.

What is a bad man but a good man’s job?

If you don’t understand this, you will get lost,

However intelligent you are.

It is the great secret.

—Lao-tzu

There was a video making the rounds some years ago of former UFC champ Frank Shamrock working on a Pilates ball. He was doing things that nobody had seen before, flowing over the ball like water, flipping, turning, and spinning—balletic and pure. Was it related to MMA or grappling? It looked like something out of Cirque du Soleil. It was graceful, beautiful to watch, the weird private workout of a strange figure in the MMA world.

Frank Shamrock rides an unsteady place in MMA history—he was a dominant champion in the UFC before the sport fully evolved, and he retired from MMA early in his career when there weren’t many good fights left for him. At times he seemed super-naturally good, working in a different league than everyone else; at other times he’s been all-too human. He’s retained some of that aura of effortless invincibility, even when he loses. He seemed like an athlete from the future, and indeed when MMA began to surge in popularity Frank emerged from retirement. Older and wiser, however, he took control of his career.

He never returned to the UFC, which he calls “U-Fight-Cheap.” He’s had a love-hate relationship with longtime MMA fans, sometimes coming across as arrogant and sneering, other times as the epitome of the humble martial artist.

When I drove out to San Jose to meet Frank at his gym, he was remarkably reasonable, relaxed, and businesslike. But every now and again a flash of a fighter’s ego would shine through, the silly self-focus of celebrity would make its presence felt. His handsome battered face could split with a jackal grin, one tooth sharp and snaggled, and a slightly wild look in his eyes. I set out the tape recorder and sat down on the mats, and Frank stretched and started to talk. There is little mystery as to why Frank is the way he is—it’s where he’s from.

Frank was born Alisio Juarez III in 1972 in Santa Monica, California, and had a hard youth. “I was a pretty serious juvie delinquent,” he laughed, but there wasn’t any humor in his voice. “I left home at eleven and was a ward of the state until I was nineteen. The state was my mom and dad.” There is something about how he said it, a catch in his voice, a veil drawn by a self-made man over a wound that will never quite heal.

“It was a joke. As long as you don’t hurt anybody, you can do anything. We’d have huge parties, steal cars, wreak havoc . . . but as long as you didn’t hurt anyone they’d just send you along to the next place.” Frank wasn’t a street fighter, though—he disliked violence and can remember only a few scraps that he couldn’t avoid. He came to the idea of fighting late.

Though Frank hadn’t played many sports besides partying, he was a natural athlete. You can tell he was one of those odd kids who had all the gifts to make it—brawn, brains, looks, but without the family support and stability to guide him. So he drifted, alone. He dabbled in volleyball, soccer, and even pitched in Little League, but he never fought much, or even wrestled. “I went to wrestling camp and the first day a couple of guys went out partying, had a great time but got in some fights and caused trouble, and they assumed it was me who led them astray,” he laughs, this time with genuine merriment. “That was the end of my wrestling career. The coach kicked me out.”

Frank eventually found his way to Bob Shamrock, who ran the Shamrock Ranch, a foster home for boys in Susanville, California. Bob had a favorite adopted son, who’d taken his name: Ken Shamrock. Ken was a promising athlete and the alpha boy at the ranch, and he would become one of the founding fighters of modern MMA. He lost to Royce Gracie in a couple of early UFCs and had a good understanding of the ground game from training in Japan for Pancrase.

Pancrase was a promotion formed by Masakatsu Funaki, a bored pro wrestler, a submission wizard who wanted to fight as the “first ever pro-wrestling group with no preordained finishes” (to quote Paul Lazenby, a fighter and a commentator). This was in 1993, the year the UFC started in the United States. The idea, like so many ideas, was floating in the ether. Ken Shamrock was one of their early stars. Ken was very much the image of a fighter, with a superhero body of muscles, a square chin, and a GI Joe haircut. Ken eventually went to pro wrestling and was billed (in his prime with some veracity) as the “World’s Most Dangerous Man.”

The three Shamrocks have had a tempestuous relationship over the years. At one point, when Frank was sixteen, Bob and Ken went to North Carolina to pursue Ken’s pro wrestling career and kicked Frank back into the system. What that must have felt like to a sixteen-year-old boy is hard to fathom.

A few years later Bob and Ken returned to California, and Frank was formally adopted. Frank started training with his new brother and found he enjoyed the fight training. “I was very, very competitive. I go a hundred percent and I want to be good or terrible. I loved submission wrestling because it was singular, self-driven. In volleyball I’d go crazy and try to be everywhere at once, and guys were loafing.”

Frank took to it like a fish to water, and remembers, “It only took a few months to start beating those around me. Ken, my first teacher, taught me the basics, catch-as-catch-can wrestling. It was the simple stuff—movement, position, submission—but I loved it and I studied it like a science and progressed fast. I wrote down everything. I took a very scholastic approach. I saw the whole thing as a game, just a sport—not a fight. I wasn’t encumbered by the idea of winning or dominating.” Frank swears he had never been a street fighter, and he often talks about how distasteful he finds violence.

Ken was a superstar in the early MMA world, and Frank lurked in his shadow, going to the big fights at the UFC and in Japan as part of Ken’s posse. He began to fight, but “I had trouble, because I didn’t want to hurt people. I didn’t really understand the game.” He was in awe of his brother, who “smashed me at will.” The gym was called the Lion’s Den, and the brutality of training (and hazing new members) has become legendary. It was the epitome of the old school macho MMA gym, the original—come get your ass kicked if you want to play with the big boys.

Frank smiled at me with that hyena grin and said, “I had to accept that if I am swordsman, if I pick up the sword, I have to swing it. That’s the game. It is what it is. A punch is a punch, and there’s a game element and an art element, but it’s also a physical altercation and if I don’t go a hundred percent something bad could happen. Being a professional fighter and not trying to hurt your opponent is the stupidest, most oxymoronic thing. I think it was a fear of being good, of having the skill to hurt if necessary. At the time I wasn’t mature enough to realize that having the skill is wonderful, that it’s a blessing. You just need to know what to do with it. Some will fight in the street, some will languish in the middle, wondering if they should commit, and some will be the best fighters in the world. I realized and accepted it, that I loved it, and I accepted what comes with it. I may kill somebody or get famous but, if I’m true to it, then I accept that. From that point on, I smashed everybody.” Frank burst into laughter again, content.

I thought of Liborio, and Freddie Roach, and the importance of

acceptance

. Here I was hearing it again, in a slightly different context, perhaps, but it also played to Virgil’s comments about perspective. Maybe I was finally getting somewhere.

acceptance

. Here I was hearing it again, in a slightly different context, perhaps, but it also played to Virgil’s comments about perspective. Maybe I was finally getting somewhere.

“There was a fight early on, John Lober, where I got him in a bunch of different holds and every time I got something I’d look over at him and think, ‘Hey, time to tap, I got you.’ But he was

fighting

. He came from a different place, and he’s thinking, ‘Just break my leg or I’ll get out.’ He forced me to confront the truth of fighting. It was a big growth moment for me.” Frank cackled. “Now I’ll stomp the head of my closest friend if he’s in the cage with me—that’s the game!”

fighting

. He came from a different place, and he’s thinking, ‘Just break my leg or I’ll get out.’ He forced me to confront the truth of fighting. It was a big growth moment for me.” Frank cackled. “Now I’ll stomp the head of my closest friend if he’s in the cage with me—that’s the game!”

Frank’s rise was meteoric. “I got really good and famous, really fast,” he said, and he’s right. He started fighting in Pancrase in Japan and suddenly he was matched, after only a few fights, against Funaki himself—the legend, the guy who had trained his brother, Ken. “I had to fight my teacher’s teacher. I couldn’t touch Ken. Ken could smash me at will. No matter how much I thought about it, or visualized, I didn’t see how I could beat this guy. So do I just go out there and die?” Frank laughed again.

Frank taught himself to meditate in hotel rooms in Japan. “The logic wasn’t there, of a way to beat this guy,” he says, “and I had so much fear and anxiety. I had to try something. I got inside myself, just trying to calm down. I was sitting in the hotel, thinking, ‘Oh my God what am I doing?’ when I realized I had to relax. So I worked on it. Deep breaths, eyes closed, just thinking about individual techniques. I relaxed and it worked. I started to do technical visualization. Then I went out there and Funaki kicked the shit out of me.” Frank dissolves into feral cackles, genuine deep amusement. “Yeah, he smashed me, but I came back and beat him later. And it never bothered me to lose like that. If I didn’t try hard enough, or screwed around, or was out of shape . . . those losses really bug me. If somebody kicks my ass—that was all you, dude. I have tremendous respect for them. Truthfully, that’s kind of what I’m looking for, someone who can do that and push me.” A sincerity came through those pat sporting words, a deep underlying need to be

challenged

.

challenged

.

Without a challenge, the top fighter has a hard time staying motivated, staying in the gym and doing what he needs to do. It’s fun at first, but after years and years of it, working out acquires a deadly dullness that needs a sharp point to pierce. And on fight day, unless he’s facing a really tough challenge, chances are he A) won’t get to show his skills and perform and B) won’t mentally be sharp. Most great fighters perform well only against great challengers, and often they give lackluster performances against mediocre opponents.

“For my guys, my fighters who lose, I tell them it’s a learning experience. I do my job as a trainer and make sure they’re not in there with someone who’s just way too good for them, out of their league. So I can honestly say to them, ‘Here’s the lesson,’ and if you learn it, it was worth it one hundred percent.”

Frank studied bodybuilding before he got into fighting. He brought a physical trainer’s mind-set—an understanding of musculature, anatomy, and force—to his grappling and later his striking.

“I was looking at the body and thinking about the angles and applied force in the holds, the strength and leverage of a body part. I look at someone and can see where they’ll be strong, where they’ll be weak.”

Frank’s a self-made man. Without an experienced trainer raising him, he was forced to be his own sage and expert. “I came up in submission wrestling, but I’m at the point where positions don’t matter in my world—not position for it’s own sake. How much energy are you expending? How much damage are you applying and how much damage is being done to you? Those are the big three. I like the endless flow of attacks, because it evens out the technical aspects. You may have a good grappler who’s a hundred times better than me, but when the flow never stops he has to have the muscular and vascular systems to keep up the pace.”

Frank and I sat in the dark in a wrestling room and Frank stretched slowly. He was perfectly content and relaxed, all business. I asked him to describe his mental process, and he willingly lectured, handing out self-evident truths.

“The mental side is broken into three areas or levels. One: the idea, the visualization or conceiving side. It’s hard to equate it to anything other than those positive-affirmation, self-help type of things. Olympic skiers visualize the course. For me, I do it for everything I do, not just fighting. Now that I’m commentating on live TV, I play it out in my head a bunch of different times, seeing ways it could go, making sure I hit the points I want to hit.

“The second part is replicating—just practice. It’s hard to believe something will work if you’ve never pulled it off. You practice the moves. The fighting ones are obvious, but for this last press conference I rehearsed with the fighters, I walked them through it, got them used to the sound of my voice. It chilled everyone out.

“The third part is doing, and every time you do it you get better. It takes less energy and stress.”

Frank paused in the dark. “So, one, two, three, and I end up with a result, but then I evaluate it. I think about changing what I did, and this is where a lot of people fall down. They go through a good process, end up with a result, and think it’s just fine. I won but I went to the hospital afterward.”

He smiled, his teeth flashing in the gloom. “Fighting is like a business. If you did a deal and you came away with twenty percent of the company and somebody owns you, you need to do things differently. If you won the fight but you’re in the hospital, did it really work out for you?”

Other books

Seaside Seduction by Sabrina Devonshire

Him Her Them Boxed Set by Elizabeth Lynx

Sweet Silken Bondage by Bobbi Smith

Toxic Bad Boy by April Brookshire

The Rogue Knight by Vaughn Heppner

The Parasite War by Tim Sullivan

Falling Sky by James Patrick Riser

The Hidden Light of Objects by Mai Al-Nakib

The Omega Team: Hot Target (Kindle Worlds Novella) by Jordan Dane

Low Country by Anne Rivers Siddons