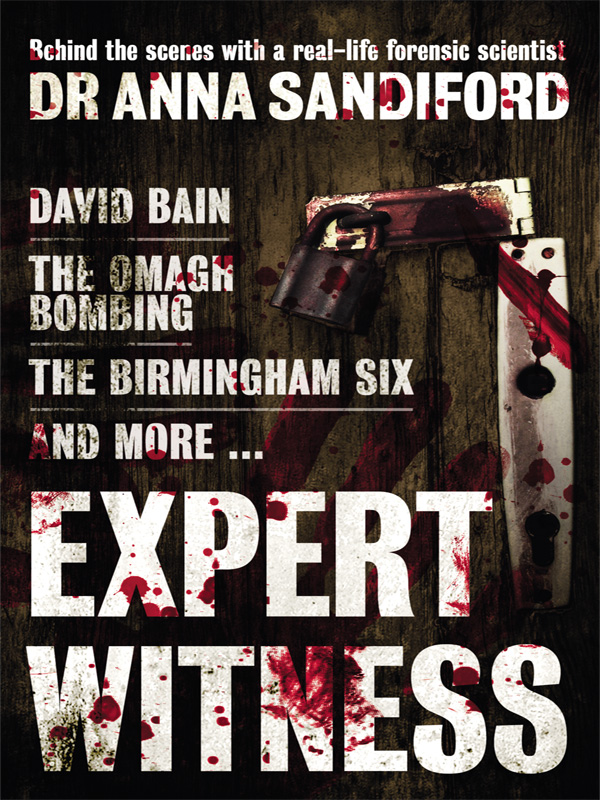

Expert Witness

1

Forensic science: the real world

2

Remind me again, how did I get here?

3

The nitty-gritty of the job

4

The

CSI

effect

5

Forensic science break down

6

The arena

7

The lion's mouth

8

The perpetual case of drinking

9

The pieman and the circus

10

The case of trace

11

Pollen

12

Those 1960s, drug-takin' Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers (and Fat Freddy's Cat)

13

Walk along the imaginary line until I tell you to stop

14

Smelly shoes and stinky socks

15

The police

16

The case of the heebie-jeebies

17

David Bain

Dr Anna Sandiford is an independent forensic science consultant. She provides advice on forensic science for a wide range of clients, including barristers and solicitors, insurance companies, private investigators, private clients, police forces and intelligence agencies. As an expert witness, she has an overriding duty to assist the Court impartially on relevant matters within her areas of expertise.

Dr Sandiford has worked in forensic science since 1998 and has been involved with cases throughout New Zealand, the UK and, on occasion, the Channel Islands and the Cayman Islands. She is director of The Forensic Group, a forensic science consultancy based in Auckland.

Â

T

his book is about my job and the casework in which I have been involved. I didn't plan on this being my job, but that's the way it's turned out. Being a forensic scientist is a very serious matter and is taken very seriously in day-to-day life. What forensic scientists do has a direct impact on people, which will affect those people and those around them for the rest of their lives. This is the aspect of the job with which most people are familiar because of media portrayal, television dramas and such like.

However, as in any job, there is a certain degree of monotony that comes with spending hours being stuck in traffic jams and dealing with bureaucracy. At the other end of the spectrum are the amusing things that come out of investigating death, destruction and general law-breaking (it is a well-known phenomenon that people who face the most traumatic situations every day manage such difficult circumstances by trying to make light of them and finding things funny; it's human nature and a safety mechanism). The humdrum and the amusement are the aspects people don't consider about forensic scientists' jobs, but they're the things that help us remain sane and functional.

I'm hoping this book will provide an indication of how forensic science is applied in a practical sense and give you an idea of what the job actually entails. With the exception

of the David Bain case (which is pretty much public property these days), I have blurred the facts slightly or changed details (or just been thwarted in providing exact detail due to some of these things happening so long ago) so that the people and cases I write about can remain anonymous. While some people may think they recognise cases or situations, rest assured, every attempt has been made to prevent this happening.

My purpose in providing case examples is to demonstrate how the forensic science was applied or what happened in a situation, not to point fingers at particular criminals, lawyers or other individuals. The case examples are purely illustrative. I also refer to forensic scientists as expert witnesses or just experts. In this book, these terms are interchangeable.

Â

When I'm not writing books or blog posts, I work as an independent forensic scientist and researcher. As far as qualifications go, I hold a Bachelor of Science (Honours) degree in Geology and a Master of Science in Micro palaeontology (micro fossils), both from the University of Southampton, England. I also hold the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geology and Palynology (pollen analysis) and a Postgraduate Certificate of Proficiency in Forensic Science, both from the University of Auckland. Some people would say that eight years as a student is far too many, but it just took me a while to find out what I wanted to do with my life.

I am Director of The Forensic Group, a company which aims to be New Zealand's most comprehensive independent forensic science consultancy. I am accredited with The Academy of Experts, a United Kingdom-based international accreditation organisation, and I am a Professional Member

of both the Royal Society of New Zealand and the United Kingdom Forensic Science Society. I am also Secretary of the New Zealand Independent Forensic Practitioners' Institute. All these memberships mean I am governed by several codes of conduct and ethics and that I am required to be impartial in my work.

I have been involved with forensic science since 1998, and until 2002 I was a forensic science consultant in New Zealand. Between 2002 and June 2008 I was employed first as a forensic science consultant, then subsequently a senior forensic science consultant and ultimately practice manager with a forensic science consulting company in England. As part of those roles I prepared more than one thousand reports on a variety of evidence types, largely for the defence but also for the prosecution. I also peer-reviewed and assessed a further one thousand-plus reports in a wide variety of forensic scientific fields.

A significant part of my role over the past 10-plus years has been the review of other scientists' files as a peer-reviewer for accreditation purposes and as an expert appointed by either the Crown or the defence. I have reviewed dozens of files from ESR in New Zealand, all of the laboratories of the Forensic Science Service and LGC Forensics, the two main service providers in England and Wales, as well as casefiles from independent laboratories in England and Wales plus police forensic science laboratories in Scotland, the Channel Islands and the Cayman Islands.

One of my roles as a senior forensic science consultant is coordination and management of cases involving more than one evidence type. I review the scientific evidence, liaise

with experts, manage the disclosure documents, organise the logistics of examination and re-examination of items and samples, arrange testing, organise Legal Aid funding and manage the general progress of the work until completion.

I have given evidence in court on more occasions that I can remember, but not as many times as I have actually been asked to attend court, but there's more about that in later pages. I regularly provide scientific advice to police forces, particularly in the United Kingdom.

In my capacity as a research scientist, I have published papers in national and international independently peer-reviewed scientific journals and I was a reviewer for the international scientific publication,

Journal of Forensic Sciences.

I am actively involved in forensic science research in conjunction with the School of Environment, University of Auckland, where I hold the position of Honorary Research Associate. I have lectured at the University of Auckland and at Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, England, in science and forensic science. I have also given science and forensic science presentations at various national and international scientific and non-scientific conferences and also at the England and Wales police Drink Drive conference. I spend quite a lot of time speaking to non-scientific groups including professionals, schools and general interest groups. You may have noticed that I keep referring to England and Wales instead of just writing âthe United Kingdom'. The reason is because the laws that govern England and Wales are different from those in Scotland; the Scottish don't use non-Scottish experts unless absolutely necessary, such as in cases involving drug traces on bank notes because there's no one else who can do that sort of

work. Ireland (Northern and Republic) also works in different ways with different police forces and different approaches. While it may seem cumbersome to write England and Wales, it is more accurate and, as a scientist, accuracy rocks!

As an expert witness I under stand that my overriding obligation is to the court and not to those instructing me. This means I won't say some thing in court that isn't true to the best of my knowledge and belief.

I

am standing in a large, old, unfurnished room with a partially carpeted concrete floor and only one exit. A convicted murderer stands between me and the exit. There's nowhere to hide. I'm kneeling on the floor with my head bowed down, close to the unmoving dirt and dust around the edges of the room. The air is hot, humid, heavy, oppressive. Sweat slowly rolls down through my hair and I hope he can't see it â it's a sign of weakness and I don't want him to know about it. I can feel him looking right at me. I feel self-conscious and I don't know whether I should meet his eye. As I look around, I see blood on the floor. Fresh blood. I'm so close to it I can taste it at the back of my mouth. I know it's fresh because I saw it spill onto the floor. I try not to breathe it in but I can't help it, it's everywhere I look. There are bloodied sock prints across the entire floor, made by the convicted murderer as he paced about.

This isn't just any murderer, he's notorious, infamous. He was tried and convicted of five murders and sentenced to a mandatory life term in prison, minimum parole period of 16 years. Yet here he is after 12 years, standing between me and my only way out. This was my own choice. I invited him into this room and now I'm in here with him. I know the door's unlocked but there's a chair pushed up against it to stop it being opened from outside. The man brought someone

with him, another man, who is forthright and solidly built, determined.

The questions in my mind could be, am I afraid? How can I get out of here alive? The actual question is, how big are his feet? The man in question is David Bain. The man with him is Joe Karam. I am here because they have asked me to assist the defence team for his retrial. I am here because I am a forensic scientist.

Â

Now that we know why I'm in this situation, let's look at that scene again. I am standing in a large, old, unfurnished room with a partially carpeted concrete floor and only one exit. The carpet has been put down by me and consists of strips of different types: a section of wool-rich cut pile here, a section of synthetic cut pile there. There are also long sheets of paper underneath the edges of the carpet to prevent blood getting on the concrete. Unsealed concrete is absorbent and it'll soak up the blood, which I don't want.

David Bain does indeed stand between me and the exit. That's because he's been told to stand there while I finish getting every thing sorted out. I'm kneeling on the floor with my head bowed down, close to the unmoving dirt and dust around the edges of the room. I'm doing this so I can label each carpet section so they don't get mixed up.

The air is hot, humid, heavy and oppressive. I'd forgotten just how hot it can get in Auckland in summer, particularly so in an enclosed space with a metal roof, baking like an oven. Sweat slowly rolls down through my hair and I really hope neither he nor anyone else can see it â if it drips on my working notes it will make the paper damp and difficult to

write on. No windows are open and there's no ventilation â there's a Burmese cat outside desperate to get in because she can smell the blood, and she's yowling as only a cat of Far Eastern persuasion can yowl. If she gets in then we'll never get her out and she could cause havoc with the tests.

I can feel David Bain looking at me. Not surprising really, seeing as it's me who's directing him when to put his foot in cow's blood. I don't know whether I should meet his eye. I don't normally have anything whatsoever to do with defendants. In civil cases the word

defendant

can be replaced with

respondent

. Whatever they're called, I usually don't have any contact with them. Having to meet a defendant is unusual and I have to keep it impersonal. Unfortunately, this means I have to border on being rude, which goes against my instincts â I hate it when people are rude to me; there's just no need for it.

As I look around, I see blood on the floor. Fresh blood, which I can taste at the back of my mouth because I'm so close to it. I know it's fresh because I saw it spill onto the floor. Well, to be honest, it didn't exactly spill, more of a pour-into-a-tray than a spill. It's fresh because I collected it from a supplier this morning, who got it from an abattoir even earlier in the day. It's whole blood so that it mimics as closely as possible the way whole human blood behaves when it's liberated from the body. âWhole blood' is the term used to describe blood from which nothing has been removed. Serum, platelets, fibrinogen and other components of blood can be removed from it to be used for a whole range of things, mostly in the biomedical field. In fact, the company that provided me with this blood usually provides antibodies, serum and other biological mixes for diagnostic testing purposes. They clearly thought I was

mad when I asked if I could have some whole blood so we could walk it around the floor using feet and socks.

There are bloodied sock prints across the entire floor, made by David Bain as he paced about. This is a good thing. We're testing the length of the sock prints he would make if he walked in blood and then walked across carpet.

The door's unlocked but there's a chair pushed up against the door to stop it being opened from outside. This is to stop anyone walking in by mistake and also to prevent accidental admission of said cat.

The man who accompanied David Bain is Joe Karam, who I think is fairly described as forthright and solidly built; he looks as if he might have played serious sport at some point in his life. He was, in fact, an All Black and he looks determined because he is. He's also very focused. He's fought long and hard for this retrial and it's approaching at a rapid pace. When David Bain and Joe Karam arrived to do these sock-print tests, it was two weeks before the scheduled start of the trial. Luckily for me, the start date was delayed by another two weeks, until 6 March, which gave me a bit more report preparation time. Never rush a scientific report, especially if it's to be used in court, more especially if it's going to be used in what has been termed the âtrial of the century' by the media. It strikes me that it's the trial of the century because the media has made it that way, but what do I know? I wasn't here when the killings occurred in 1994, I wasn't here for the first trial or the appeal. I'm not even a real Kiwi.

This man isn't just any murderer, he's notorious. This is true â at this stage he was one of the most, if not

the

most, notorious murderers in New Zealand history. When he was

22, he had been convicted of murdering five members of his family.

According to the Crown case, after he had shot four of his family, David Bain went out and completed his paper round before coming home, waiting in an alcove in the sitting room for his father to come into the house from the caravan where he was living, before shooting his father, turning on the family computer, typing his father's fake suicide message and then calling the police.

In 1995 David Bain was tried, convicted and sentenced. In 2007, the Privy Council in London determined a gross miscarriage of justice had occurred. The New Zealand Solicitor General ordered a retrial, which took place in 2009, between 6 March and 5 June.

Â

So here they both are. David Bain has obligingly put his foot in cow's blood, walked around some pieces of carpet and gone home. Joe Karam has departed as well. I'm left with the prospect of shifting sections of carpet to a photographic laboratory so they can be sprayed with a blood-enhancing chemical and photographed under special lighting conditions. Because this is mid-summer, it doesn't even think about getting dark until 10 p.m., which means it's going to be a late night. Luminol, the blood-enhancing chemical I am testing with, needs to be used in darkness. The photo studio doesn't have full window coverings so we have to wait until it gets dark. By the time the sock prints have been sprayed, measured, sprayed again and photographed, it's 2 a.m. and I'm tired, dehydrated (standard laboratory practice: no drinks or food) and, not for the first time and not for the last, I'll wonder what the hell

possessed me to think that being a forensic scientist was such a bloody good idea.

Because the general perception is that I work exclusively with dead people, I'm asked now and then if I've ever been aware of my own mortality? In a word, yes.

I've always been pretty good at disassociating my conscious brain from my work. That's largely helped by not having to deal with actual suspects or victims very often. From that point of view, my role is quite unique. Where else in the criminal justice system do people involved with crime routinely have absolutely nothing to do with the people involved in those crimes? Think about it: everyone else in the criminal justice system has direct contact with people who were involved with the actual events. They might be victims or suspects, convicted criminals or the wrongly convicted or the families of all of those people. Fire fighters, police officers, social workers, judges, court officials, barristers, solicitors, crime scene examiners, pathologists, prosecution forensic scientists, the list goes on. Even in insurance work, the private investigators, insurance company representatives, legal counsel for the insurance companies â the one thing they all have in common is that they generally have direct involvement with the people involved in the key events. Independent experts who are instructed some time after the initial events are probably the only people who don't.

If you happened to be an expert working largely for criminal defence lawyers, and if you played your cards right, you could spend practically your entire career avoiding direct contact

with the nasty end of crime. Of the thousands of drink-drive related statements I have written as an expert for criminal defence or insurance lawyers, I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of defendants/claimants with whom I have actually had any kind of conversation. And that was in those rare cases when they insisted on having their breath alcohol elimination rates estimated. Such circumstances involve them coming into the office at 9 a.m. and drinking the best part of a pint of vodka, so we can measure their breath alcohol level at regular intervals. There was also a nerve-wracking situation at court once, when I was stuck in a windowless interview room with a defendant, his dad and their solicitor between me and the door, but generally speaking it's been trouble-free.

So I guess it's been easier for me to block out the horror of what is involved in real life crime, and it certainly makes it much easier to interpret the facts in a dispassionate and impartial way. Imagine my shock when I realised I should consider myself lucky to be alive.

I didn't have one of those near-death experiences I hear about. One such story was recounted to me by a woman I know, who was living in a remote location. She and her husband encountered a distressed man who said his wife had threatened him with a knife. The poor distressed man was sent off with the kindly woman on her own, so that he'd be safe from the knife-wielding wife, while the husband went to see if he needed to call the police. The kindly woman took the distressed man to her house and settled him in the kitchen for a nice cuppa. Turns out that rather than being the victim, the man had been the attacker. He'd had a pop at his wife with the knife. The kindly woman now found herself on her own

with a madman in a kitchen â with knives. She had to try to remain calm and handle the situation before he lunged at her with a Sabatier. She survived to tell the tale, which is more than the man's attacked wife â he murdered her two weeks later, stabbing her to death.

I did, however, find out that I had spent six weeks camping, in a tent on my own, in an area where, and at a time when, a serial killer was at work. Most disturbing of all was that, at the time, the police didn't even know they had a serial killer on their hands.

In 1990 I was at the end of the second year of my undergraduate degree in geology. As part of the course we were required to undertake a six-week field-mapping course. Officially, this involved going to a selected location and applying recently learned geological skills to an actual area of country side, of which we had no prior geological knowledge. We were to collect data, then use this to interpret the underlying geology to produce a geological map of the area. In reality, for me this was a prime opportunity to wander around the countryside, do some fieldwork and have a blast enjoying Belgian beer and cakes. I chose to go to the Ardennes region of Belgium with four fellow geologists. The other options were Southern Ireland (structurally complicated â not my cup of tea), Spain (we'd been on a field trip to Spain the year before and I fancied a change) or somewhere in South America (too many poisonous spiders). Looking back on it, I guess I was never going to be a field geologist. Of our party of five, I was one of three who camped, and the only one who camped alone. Two shared a tent, although they denied it, and the other two shared a caravan.

I was reading Stephen King's

It

at the time, which features a particularly nasty clown. As anyone who has read the book will know, it also involves some spooky stuff with hands reaching out of stormwater drains and dragging people off to a nasty demise. Unfortunately, to get from the camping area at the bottom of a valley (total number of tents at any one time: two) you had to cross a bridge over a wide stream. Very picturesque in the daytime. Scary as you like at night. I never, ever crossed that bridge after dark. I was clearly deluded that the flimsy, flapping, woven, waxed and non-cutproof tent sides would protect me from marauding monsters, mad clowns and raging murderers.