Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (33 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Inflammatory bowel disease

Both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are common conditions in hospitals and outpatient clinics. They present both diagnostic and treatment problems. Mutations in the

NOD2

gene (also called

CARD 15

) increase the risk of Crohn’s disease (ileal and fibrostenosing). The patient will usually know the diagnosis, but you may have to decide which type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is present.

The history

1.

Find out about symptoms at presentation and, if relevant, the current reason for admission. Ulcerative colitis (UC) typically presents in young adults with relapsing bloody diarrhoea, malaise, fever and weight loss. Crohn’s disease can present like UC or can have a variable presentation, including an insidious onset of pain, diarrhoea, weight loss, malabsorption, intestinal obstruction or symptoms suggestive of ‘appendicitis’.

2.

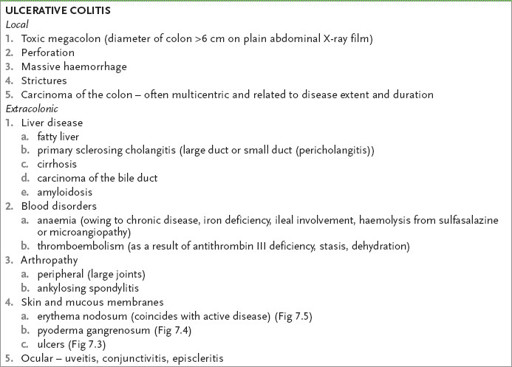

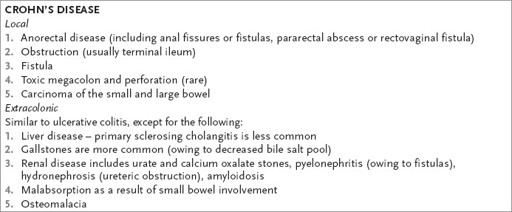

Ask about local complications and extracolonic manifestations of the disease (

Table 7.4

).

Table 7.4

Complications of inflammatory bowel disease

3.

Enquire about sexual orientation if relevant (infective proctitis in men who have sex with men must be considered in the differential diagnosis).

4.

Ask about medications – NSAIDs, retinoic acid and possibly oral contraceptives can cause a similar picture.

5.

Determine the investigations at the time of presentation and subsequently (and particularly whether infectious causes were considered).

6.

Ask about the number of hospital admissions.

7.

Ask whether regular follow-up colonoscopy has been performed in patients with longstanding colitis.

8.

Find out about treatment, including medications – such as sulfasalazine, 5-aminosalicylic acid preparations (mesalazine, olsalazine), local or systemic steroids, budesonide, metronidazole, immunosuppressants (e.g. azathioprine), other antibiotics (consider pseudomembranous colitis), infliximab or adalimumab (tumour necrosis factor antibody) – and a detailed surgical history.

9.

Enquire about family history of inflammatory bowel disease or bowel carcinoma.

10.

Ask about smoking – a greater proportion than average of Crohn’s disease patients are smokers and the risk of developing ulcerative colitis rises when people give up smoking.

11.

Enquire about the patient’s domestic arrangements and employment.

The examination

A thorough gastrointestinal system examination is important. Evaluate the general state of nutrition and hydration. Feel for any tenderness or abdominal masses and look for anal lesions externally. Always ask for the results of a rectal examination. Look for the signs of Cushing’s syndrome if the patient is taking steroids. Search for the other extracolonic manifestations, being guided by the history (e.g. arthropathy, skin lesions, uveitis, anaemia, liver disease).

Investigations

It is important to exclude other causes of colitis (

Table 7.5

). For the investigation of inflammatory bowel disease, the following should be considered.

Table 7.5

Causes of colitis

1.

Inflammatory bowel disease

2.

Infections, including pseudomembranous colitis

3.

Radiation

4.

Ischaemic colitis

5.

Diversion colitis (colonic loops excluded from the faecal stream)

6.

Toxic exposure (e.g. peroxide or soapsud enemas, gold-induced colitis)

7.

Microscopic or collagenous colitis

8.

Lymphocytic colitis

1.

Infection must be excluded

. The causes include amoebiasis (diagnosed by rectal mucosal scraping or warm stool examination),

Shigella

,

Salmonella

,

Yersinia

,

Campylobacter

,

Escherichia coli

0157:H7 and pseudomembranous colitis (

Clostridium difficile

toxin). Lymphogranuloma venereum (a chlamydial disease that is sexually transmitted), gonorrhoea and syphilis (particularly in men who have sex with men), and other infections in immunocompromised hosts (e.g. herpes, cytomegalovirus, cryptosporidium,

Isospora belli

) should be considered in patients at risk.

Remember that TB can, uncommonly, mimic Crohn’s disease. Also, reactivation of TB is a major risk with anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: a chest X-ray and tuberculin skin test are mandatory before starting this therapy.

2.

Plain abdominal X-ray film

. It is important to look for bowel wall thickening (oedema), gaseous distension and evidence of toxic megacolon in ulcerative colitis. In Crohn’s disease also look for loops of matted bowel and small bowel obstruction.

3.

Blood count

. Check for anaemia (caused by chronic disease, blood loss, macrocytic anaemia in ileal disease, or haemolytic anaemia from an autoimmune process, microangiopathic disease or sulfasalazine). Check the white cell count (e.g. leucopenia from azathioprine). Look at the ESR (or CRP) for evidence of active disease.

4.

Liver function tests and blood levels of electrolytes, urea and creatinine

. These patients may develop liver disease. Crohn’s disease may lead to renal stones, pyelonephritis, hydronephrosis or amyloidosis. Remember that hypoalbuminaemia is a sign of severe disease.

5.

Barium enema

. This is only rarely used to make a diagnosis. It is contraindicated in very active colitis and with toxic megacolon because of the risk of perforation. This investigation will help distinguish ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s disease – in ulcerative colitis the rectum is nearly always involved and there are no skip lesions. Look for loss of haustrations, mucosal irregularity and ulceration, spasm, pseudopolyps and bowel shortening. Also look for evidence of strictures and carcinoma. In Crohn’s colitis, look for thickening, ‘cobblestoning’, luminal narrowing, skip lesions, fistulas and transverse fissures (sinus tracts).

6.

Colonoscopy

. This is a very useful investigation to assess whether disease is patchy or not and to assess its extent; the test is more sensitive than a barium enema. Note decreased mucosal translucency, loss of vascular pattern, granular and friable mucosa, hyperaemia, ulceration and pseudopolyps in the report. Mucosal biopsies may not differentiate ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s disease. Mucus depletion and prominent crypt abscess formation are more suggestive of ulcerative colitis. Granulomas (in 25%) or focal inflammation are found in Crohn’s colitis (but, note, granulomas also occur in biopsies from

Chlamydia trachomatis

and syphilitic proctitis or in cases of tuberculosis). Patients with ulcerative or Crohn’s colitis who have had pancolitis for more than 7 years or left-sided colitis for 15 years or more should have colonoscopic screening with biopsy offered every 1 or 2 years to look for high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma. If high-grade dysplasia is confirmed in the absence of severe inflammation, colectomy is indicated. If severe inflammation is present, assessment for dysplasia may be misleading.

7.

Antibody testing

. The presence of perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) and anti-

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

antibodies (ASCA) does not make the diagnosis, but p-ANCA-negative and ASCA-positive patients are more likely to have Crohn’s disease than ulcerative colitis (the test is specific but not sensitive).

Treatment

ULCERATIVE COLITIS

In ulcerative colitis, grade the severity of the disease:

•

mild

– fewer than four bowel motions per day, minimal bleeding, normal temperature and pulse

•

acute

severe

– more than six motions per day, profuse bleeding, temperature >37.5°C, pulse >90 beats/min, abdominal tenderness

•

fulminant

– more than 10 motions per day, continuous bleeding, fever and tachycardia as above, abdominal tenderness and distension.

Other useful indices of severity are anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia and acute phase reactants (e.g. ESR, CRP).

1.

In an acute attack, remember to correct hypokalaemia and avoid barium enema to prevent toxic megacolon or perforation. Do not prescribe opiates or anticholinergic agents for the same reason. In severe colitis, intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics (including metronidazole) are usually given. Intravenous steroids are the mainstay of treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe disease. Cyclosporin may be given intravenously as a short-term alternative to colectomy for patients who do not respond to steroid treatment. Infliximab is an alternative. Close cooperation with a surgeon who is interested in this field and with stoma therapist is important early on in severe disease; these consultations provide information and psychological support.

2.

In mild-to-moderate disease, sulfasalazine is useful; mesalazine is the active agent, while sulfapyridine is the cause of most intolerance (allergic reactions such as skin rash – including Stevens-Johnson syndrome – and Heinz body haemolytic anaemia; and side-effects such as nausea, headache, folate deficiency and reversible male infertility). The minimum dose is 4 g per day. Sulfasalazine decreases the relapse rate and administration should be continued indefinitely.

Mesalazine is as effective as sulfasalazine but has fewer side-effects and higher doses may be given. Mesalazine is useful for patients with sulfasalazine intolerance. Note that the alternative, olsalazine, may cause diarrhoea in patients with active ulcerative colitis (because of ileal secretion) – as a result, it is normally used as maintenance treatment. Chronic steroid use does

not

reduce relapse rates. Remember to correct iron and folate deficiency if necessary.

3.

If proctitis is the problem, first-line treatment is topical (steroid or mesalazine enemas twice daily) plus sulfasalazine or mesalazine orally for more active disease.

4.

Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine is useful if there are repeated episodes of ulcerative colitis. Side-effects include pancreatitis in 3% of patients and reversible bone marrow suppression in <10% of patients. The use of methotrexate is controversial.

5.

It is important to try to differentiate ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s disease using the clinical presentation, X-ray, endoscopic and histological findings. This is because ulcerative colitis that does not respond to medical management can be cured by colectomy; patients with extensive ulcerative colitis are at an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer. In up to 10% of patients, a specific distinction cannot be made.

Colectomy in ulcerative colitis is curative. Indications for surgery include chronic ill-health and severe disease, complications (e.g. perforation, massive bleeding) and severe disease not responding to optimal medical treatment in 7–10 days.

Patients with a very high risk of carcinoma (confirmed high-grade dysplasia on biopsy or dysplasia in a lesion or mass) should be advised to undergo a colectomy. All manifestations of the disease are cured by colectomy, but ankylosing spondylitis, liver disease and occasionally pyoderma gangrenosum do

not

respond.

While the standard Brooke ileostomy is the simplest procedure, the ileal pouch anal anastomosis is increasingly being used as it maintains intestinal continuity, although it does leave the patient with four to eight bowel movements daily and sometimes with minor incontinence (20%), and is often complicated by pouchitis (in up to 50% of patients). The latter usually responds to treatment with metronidazole or probiotics.

CROHN’S DISEASE